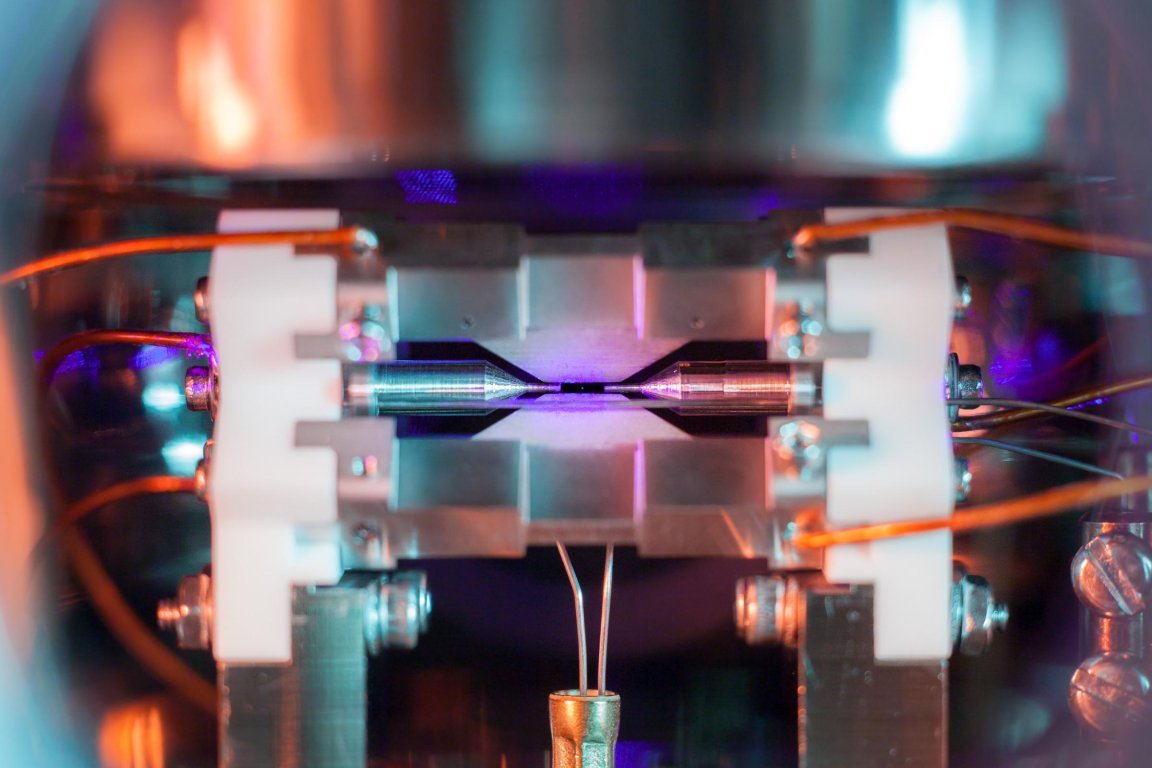

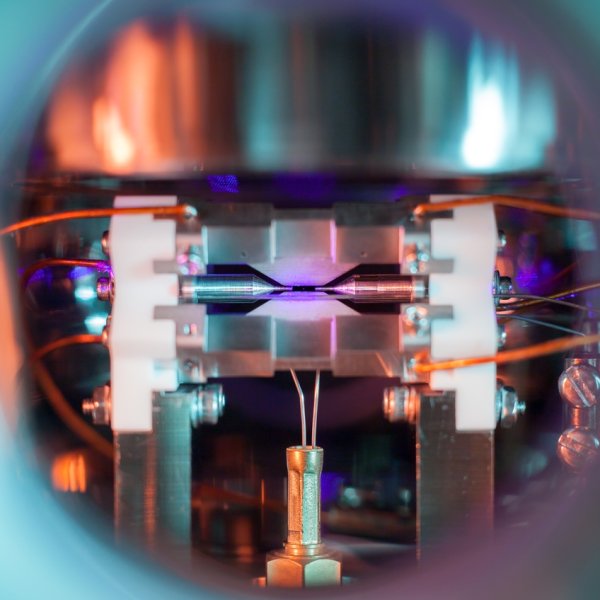

Copper wires. Metal bars and cylinders. All converge on one tiny, pale dot.

Physicist David Nadlinger captured a single atom, and made it visible to the naked eye. The photo, “Single Atom In An Iron Trap,” won the 2018 Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council science photography competition. Nadlinger captured the award-winning shot with the help of two electrodes, a magnetic field, and a strong laser at an Oxford University laboratory. A single strontium atom with a radius of around 215 billionths of a millimeter, illuminated by a bright laser, appears in the image captured by an average consumer-grade camera and one simple long exposure.

This image captures the viewer’s imagination, making the abstract visible and tangible. Photographs of scientific feats have the power to make the viewer see their world just a bit differently. Sometimes, these images can even change government policies, igniting action, ending wars, or encouraging scientific discovery.

This image is hardly the first image to capture the imagination thanks to science. Back in the 1960s, the Soviet Union and the United States were embroiled in a decades-long battle to forge new paths exploring the unknown beyond Earth. On July 20, 1969, the U.S. made a bold advance in that competition; 38-year-old NASA astronaut Neil Armstrong didn’t just make history, but he also immortalized it. With the crew’s 70mm Hasselblad camera in hand, he captured a series of simple exposures of the surface of the Moon that forever altered, and expanded, humanity’s perspective.

Armstrong’s one small step was the first of many his colleagues at NASA have taken to send humans beyond Earth. Though funding for these programs has ebbed and flowed in the years since the first Moon landing (it peaked in the years leading up to it), it’s hard to imagine that the U.S. would have continued to fund efforts to explore the rest of our solar system and beyond if those projects didn’t return such stellar images (let’s not forget the most striking pale blue dot — Voyager 1’s photo of Earth snapped in 1990).

Other photos, brought about thanks to scientific advances, changed how we see the world, or what we can see of it. In 1895, while experimenting with glowing cathode tubes that emitted unusual frequencies, Wilhelm Röntgen captured an unprecedented image of the inside of the human body — it was the first x-ray image (of his wife’s hand). X-rays are, of course, now used in medicine and beyond, helping doctors diagnose broken bones and archaeologists look inside sarcophagi.

Other images have inspired more fear than hope. In 1951, the threat of nuclear Armageddon loomed. When researchers tested the first hydrogen bomb, dubbed “Ivy Mike” (500 times more powerful than the uranium bomb dropped on Nagasaki in 1945), photographs of the resulting mushroom cloud made their way around the world.

Through the fears of a global meltdown, a strong anti-nuclear weapon movement emerged in the U.S. Five years after the Ivy Mike test, about 50,000 women marched in 60 U.S. cities against the creation and use of nuclear weapons — at the time the largest national women’s peace protest of the 20th century.

Each of these moments — awe-inspiring, intriguing, terrifying — frozen in time by cameras fundamentally changed the way we see and understand the world.

In 1969, Neil Armstrong made us feel like ants, inhabiting a massive, desolate universe. Today, David Nadlinger has done the opposite, shattering the boundary between our reality, and the nanoscopic matter that shapes it. Both used a camera, but with astronomically different results.