There is indeed water on the Moon, NASA announced today — and not only trapped in shadowy craters, but mixed into the soil on our closest neighbor’s Sun-lit side as well. That means that Moon astronauts could have a steady supply not only of drinking water, but possibly rocket fuel as well if they break the H2O apart into hydrogen and oxygen.

The bad news, though, is that we have no clue how to extract the precious water.

“It is the same thing as we drink on Earth,” Shuai Li, a planetary scientist at the University of Hawaii and co-author on one of the new studies, told CNET. “But the abundance is extremely low. You will need to process a few thousand kilograms of lunar regolith to get 1 kilogram of water.”

In other words, you’d need to sift through a cubic meter of lunar soil to extract a small water bottle’s worth.

That’s a reality that NASA was quick to acknowledge in its own official announcement.

“We had indications that H2O — the familiar water we know — might be present on the sunlit side of the Moon,” Paul Hertz, director of the Astrophysics Division in the Science Mission Directorate at NASA, said in the statement.

“Now we know it is there,” he added on a more tentative note. “This discovery challenges our understanding of the lunar surface and raises intriguing questions about resources relevant for deep space exploration.”

The researchers suggest a lot of this water came to the Moon’s surface through a mix of battering micrometeorites, solar winds and cosmic rays. That means the water may be trapped in glass — a conundrum in itself for thirsty astronauts.

It would also still be a scarce resource — despite the fact that hundreds of thousands of square kilometers of the Moon’s surface are dotted with tens of billions of tiny ice “traps,” as one of the papers found.

“To be clear, it’s not puddles of water, but instead water molecules that are so spread apart that they do not form ice or liquid water,” Casey Honniball, a postdoctoral researcher at NASA’s Goddard Spaceflight Center, and lead author of one the papers, explained to The New York Times.

At the same time, the findings could be much worse. As detailed in a pair of papers published in the distinguished journal Nature today, at least it’s definitely water — and not hydroxyl, which is “actually the active ingredient in drain cleaners,” as Honniball told the Times.

Luckily, we may soon get answers. NASA is already planning to send a small satellite, a Caltech-led mission called Trailblazer, to the Moon to quantify and study water on the Moon.

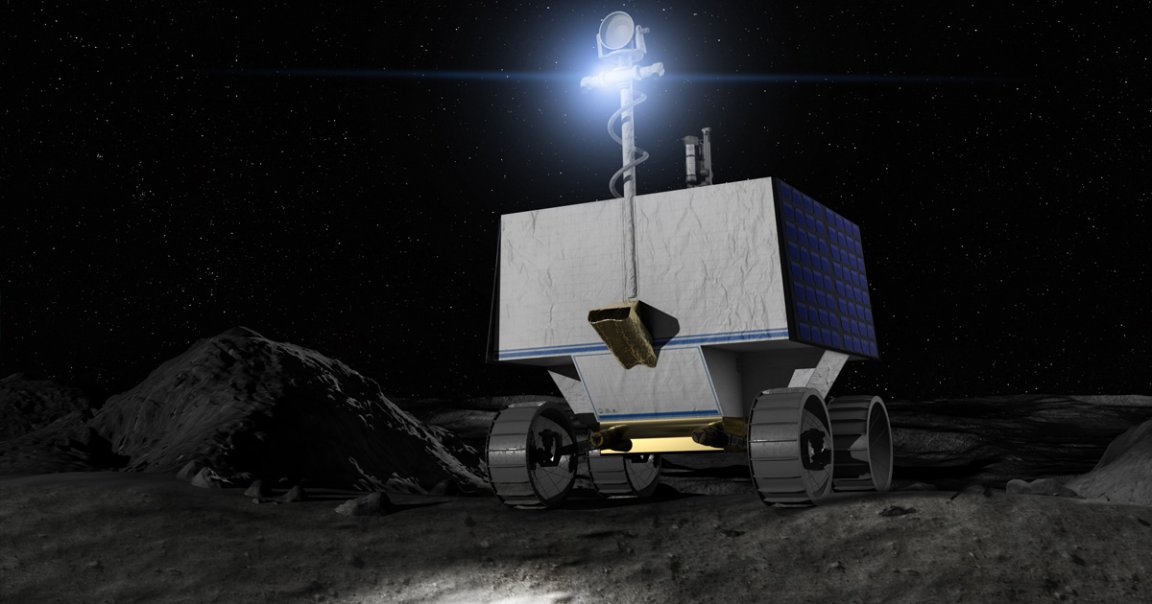

The agency is also planning to send a water-hunting rover called Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER) to the space rock in late 2023, less than a year before NASA wants to send the first astronauts to the surface of the Moon as part of its historic Artemis program.

And there are already a few ideas for extracting potable water and rocket fuel from lunar regolith.

One option is to separate water from soil by heating it up considerably using electricity, a method being investigated by Philip Metzger at the University of Central Florida.

The process, on a technical level, would be quite complex, as Metzger laid out in a brief for NASA’s Institute for Advanced Concepts program. The ice would have to be sublimated into vapor, which would then get re-frozen before being converted into vapor again for purification inside a chemical processor.

That lengthy process could be prohibitively expensive, so Metzger is suggesting that we could simplify the process considerably by running the soil through a “simple, ultra-low-energy grain-sorting process can extract the ice without phase change” instead, as he put it in a NASA brief.

The European Space Agency is also investigating ways to turn lunar soil into drinkable water — and breathable oxygen while they’re at it. By 2025, the agency wants to send a robotic mission to the Moon to begin testing mining technologies. To pull it off, the agency signed a contract last year with ArianeGroup, a space development venture.

Despite still being over a decade away, NASA’s ambitions to create a permanent human presence on the Moon, following the return of the first astronauts in just over 50 years, is slowly inching towards becoming a reality.

But having to supply the lunar surface with water could make that process extremely expensive or even pose an existential threat to such an endeavor.

Finding evidence of water on the Moon is a tantalizing prospect — but only meaningful insofar as we’re able to actually make use of it.

A telescope uncovers definitive evidence of water on the moon

More on the discovery: NASA’s Big Moon Surprise Is That Lunar Soil Contains Water