Researchers at Tel Aviv University have determined that days on Saturn are about seven minutes shorter than previously thought, thanks to a new technique for measuring the rotational period of the mysterious gas giant.

Determining the length of a day is pretty straightforward for planets with solid surfaces. With a little patience and a fairly good telescope—with a little bit of math, for good measure—almost anyone to mark the time it takes for a surface landmark to complete a three-hundred and sixty degree spin.

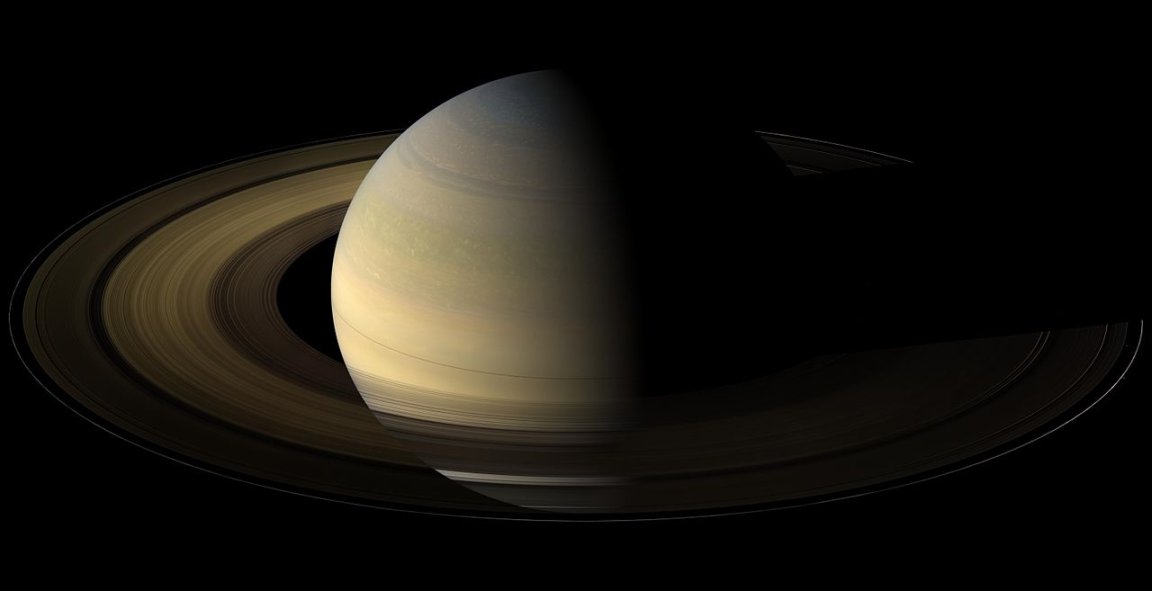

Cloud-covered planets, like Venus, or the massive gas giants further out in the solar system, present a more serious challenge. Saturn doesn’t have a surface in the same way rocky planets do. The vast gas clouds, which make up the bulk of its substance, float like terrestrial weather systems, and rotate at speeds quite different from that of the iron-nickel core presumed to lie beneath all that soup.

In the past, scientists have attempted to circumvent these difficulties using a variety of methods. For instance: Some have attempted to estimate winds and track clouds in the atmosphere, but results varied so widely, they were pretty much unusable. The most reliable estimates resulted from measurements of the planet’s magnetic field.

On their pass by Saturn on the way out of the solar system, the Voyager probes used the magnetic technique to establish Saturn’s rotational period at 10 hours, 39 minutes, and 22.4 seconds. This held up without much debate until 2004, when Cassini arrived in the neighborhood, and used the same method, only to come up with 10 hours, 47 minutes, and 6 seconds. Clearly, something wasn’t quite kosher with the magnetic measurement technique.

It turned out that Saturn’s magnetic field isn’t a reliable indicator for rotation because it is aligned precisely with the spin axis. Jupiter, which has a slightly canted field, produced more reliable results with the method, which mislead scientists as to the consistency of the technique.

The Israeli researchers went back to Cassini for their solution, but began by looking at gravitational effects rather than magnetic.

They also used the unusual fact that Saturn is taller than it is wide to confirm their measurements. Most planets, including Earth, tend to bulge a bit around the middle—the spin throwing their weight out around the waist, like a fat man doing pirouettes. Saturn doesn’t exhibit this characteristic, which aided the researchers in coming to their final conclusion.

That determination? That Saturn’s day is 10 hours, 32 minutes, and 44 seconds long.

The missing seven minutes are not, in and of themselves, particularly significant. A more accurate measurement of the period, however, will be invaluable to other scientists attempting to accurately determine the composition of Saturn’s core and lower cloud structures.

From Quarks to Quasars is two people, Jaime and Jolene.

We want to make the world a more sciencey place.

We’re doing that, but with your help, we can do even more.

FQTQ takes a lot of time, money, and effort.

Here, you can support us, get to know us, and access extra content: