It turns out that humans aren’t the only species that rely on their microbiome to stay healthy. Researchers at Ohio State University are looking at the microbial communities of corals, which appear to remain healthier in warm, acidic waters that would normally kill them when their microbiomes remain intact. That’s promising news given that warm, acidic waters are exactly what climate change is expected to deliver.

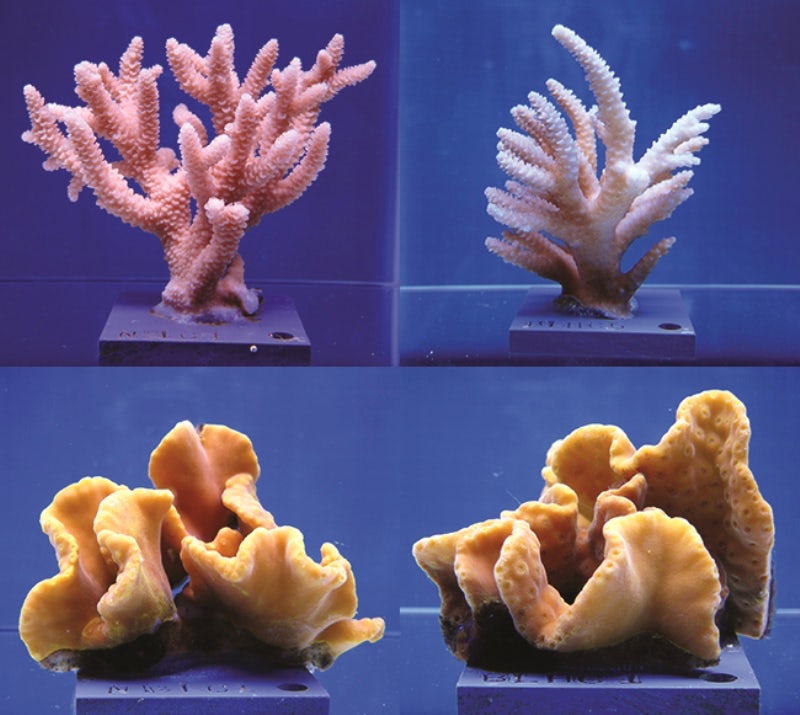

Led by researcher Andréa Grottoli, the team exposed two different species of coral to the high temperatures and high levels of acidity expected by the end of the century. Normally, when a coral experiences these conditions, it takes drastic measures: the coral animal, which builds the calcium carbonate skeleton you see when you go snorkeling, ejects its partner, a symbiotic algae that helps the coral make food. This process is known as bleaching, as the algae takes the structure’s color with it when it departs, and it usually will kill the coral.

Yet one of the corals that Grotolli’s team examined was relatively unfazed by the warm and acidic conditions. When they looked at the microbes living in a mucus layer on its surface, they also found the species living there were almost the same as before the stressful experiment. Meanwhile, the other coral studied bleached, in response to the changing conditions, and the bacteria living on it decreased in number and in diversity.

However, Grottoli’s team isn’t yet sure if the change in the microbes are just a correlation, or if they might have a causative relationship with coral health.

“There’s far more unknown than known,” Grottoli told Oceans Deeply. “We don’t know if it’s changes in the microbial community that are causing shifts in the physiology, or if it’s changes in the physiology that make the coral no longer a good host of the microbes.”

Researchers are hard at work trying to untangle that relationship. Early work certainly seems to suggest that like the humans microbiome, coral microbes help the animals to handle stress and fight off disease. The coral microbiome may even be flexible: Experiments in transplanting colder water corals to warmer environments show that the animals were able to take up new species of bacteria and survive.

This information could help scientists figure out ways to preserve corals in warmer and more acidic seas — whether that’s identifying areas with more resilient coral to protect, giving corals probiotics to bulk up their microbiome, or even breeding “super corals” that can better handle warmer seas.

Such action may be needed sooner than later. The most recent global coral bleaching event lasted over three years, and in many reefs wiped out between 70 and 100 percent of the coral there. Most reefs would need at least a decade to recover from an event of that magnitude, but scientists don’t expect they’ll have that long.