Reviving Corals

At the current restoration rate, it would take 550 years to remove the Staghorn coral, which peppers the coasts of Florida, the Bahamas, the Caribbean Islands and the Great Barrier Reef, from the list of endangered species. “What we are trying to achieve is to dramatically scale up restoration if we are going to get anywhere,” Scott Graves, director of the Florida Aquarium’s Center for Conservation, told Futurism.

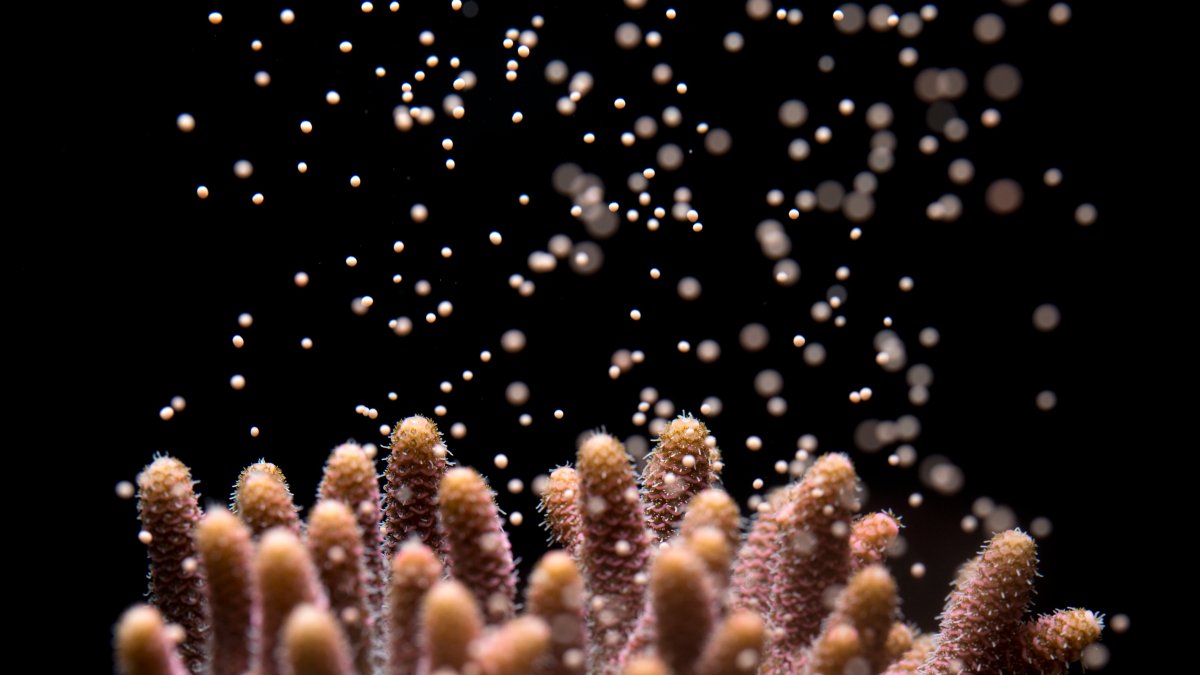

To do so, the team is importing a technique developed in the U.K. by Jamie Craggs, a researcher at the Horniman Museum in London, who has been studying how to artificially boost the natural spawning cycle of corals by reproducing specific climatic conditions in the lab. Corals naturally reproduce once a year when a fine balance of water temperature, lunar cycle and other environmental factors prompts them to release thousands of tiny larvae in the water. Graves hopes to trick them into eventually spawning once a month.

The researchers at the Florida Aquarium “will bring corals from the wild,” as “they know the genetic material they need to work on” Jamie Craggs told Futurism. “Initially spawning will happen at the same time as it does in the wild, and then we are looking to start to break the natural cycle to have lots more spawning [events].”

“From a research perspective, for someone like myself who is impatient, [a yearly spawn] is really not ideal,” Graves said, “Because you learn new things in the first few weeks, then you want to try something new and you can’t.”

The new system creates an artificial lighting environment and uses microprocessors to simulate climatic changes, making it a vital conservation tool. Currently, coral restoration relies heavily on a technique known as ‘asexual reproduction,’ which involves breaking up bits of corals, maturing them in the lab, then planting them back on the reef where they’ll reach full development.

The Need for Diversity

While that sounds promising, there’s one problem: “The bits you grow back are just clones,” said Rachel Jones, project manager of the Bertarelli Programme in Marine Science at the London Zoo, “So you are not creating a very diverse population.”

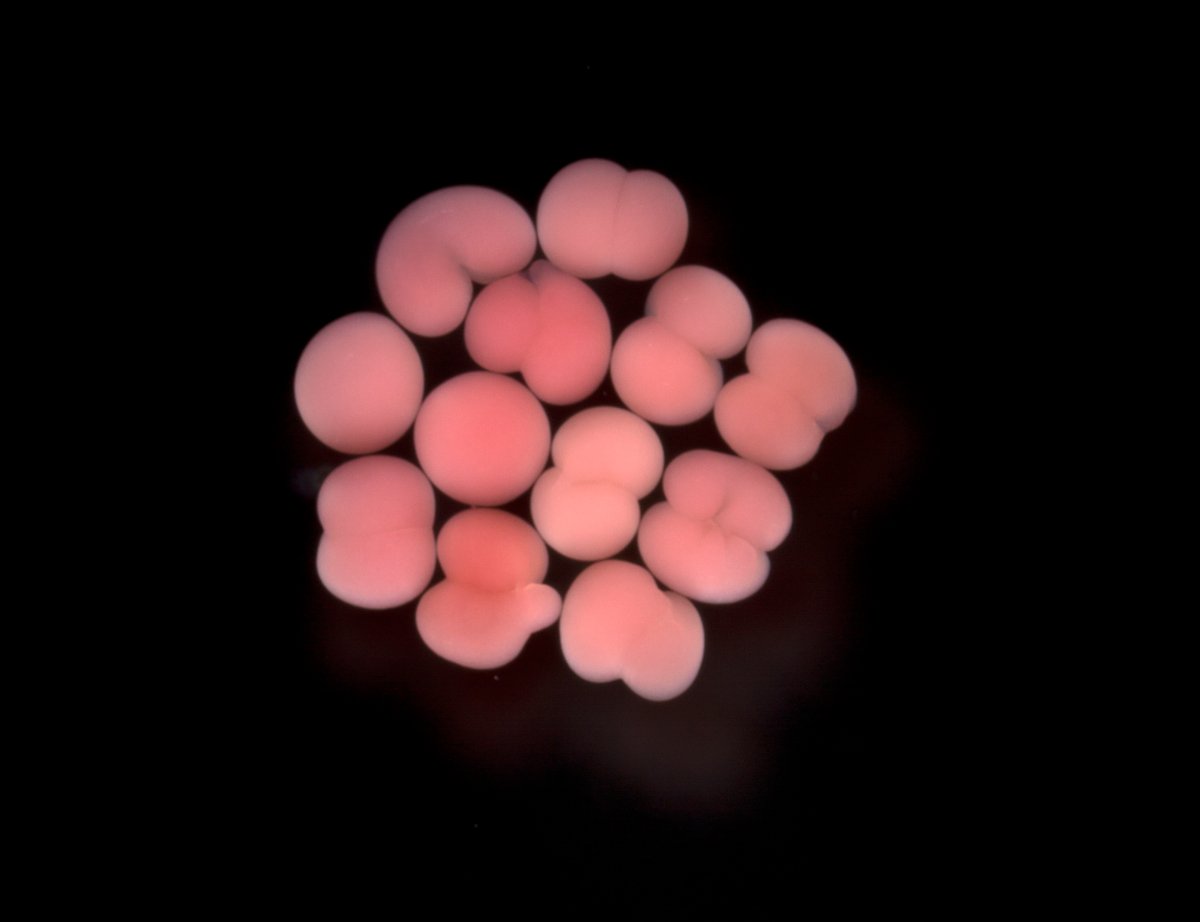

Spawning events, on the other hand, are a form of sexual reproduction — which means they generate a variety of unique genetic blueprints. As Jones explained, “If you try to do restoration, what you are hoping is that some of the genotypes that you put back on the reefs are going to survive, you hope that some of them are suited to the environment they find themselves in.”

Genetic diversity is key to help Florida’s corals withstand bleaching events and disease outbreaks such as the one that is currently wiping out the local Pillar coral. For example, researchers in the Hawaii found that areas most affected by coral bleaching often were the least genetically diverse.

Producing a higher number of larvae also increases the chances that more will make it to adulthood. Currently, “out of millions [larvae] we settle [on the reef], we might only get to survive a hundred or a thousand. This is a tremendous bottleneck.” said Graves. “Within the next year or two, we hope to be able to settle and grow millions of sexual recruits.”