Some galaxies are elliptical, some are spiral; some are bright, whilst others are blurry; some are small and some are large, but they never start out that way; How galaxies grow from seeds to gardens full of stars is subject to debate, but astronomers currently believe galaxies become large by gobbling up their neighbors. These mergers usually leave lots of evidence behind, like warped disks, tidal tails of material, and supermassive black holes sometimes awaken from their slumber. However, much remains unknown, especially concerning incoming stars and star formation materials.

For instance, astronomers wonder how the companion’s stars—known to yield insight into into the galaxy that was consumed—are redistributed post-merger. Team members offer an analogy of a glass of water being thrown into a pond. If you were to empty its contents, the new water’s molecules would immediately mingle with those of the preexisting water, which would make it difficult to differentiate the new from the old. The same can be said for stars involved in galaxy mergers.

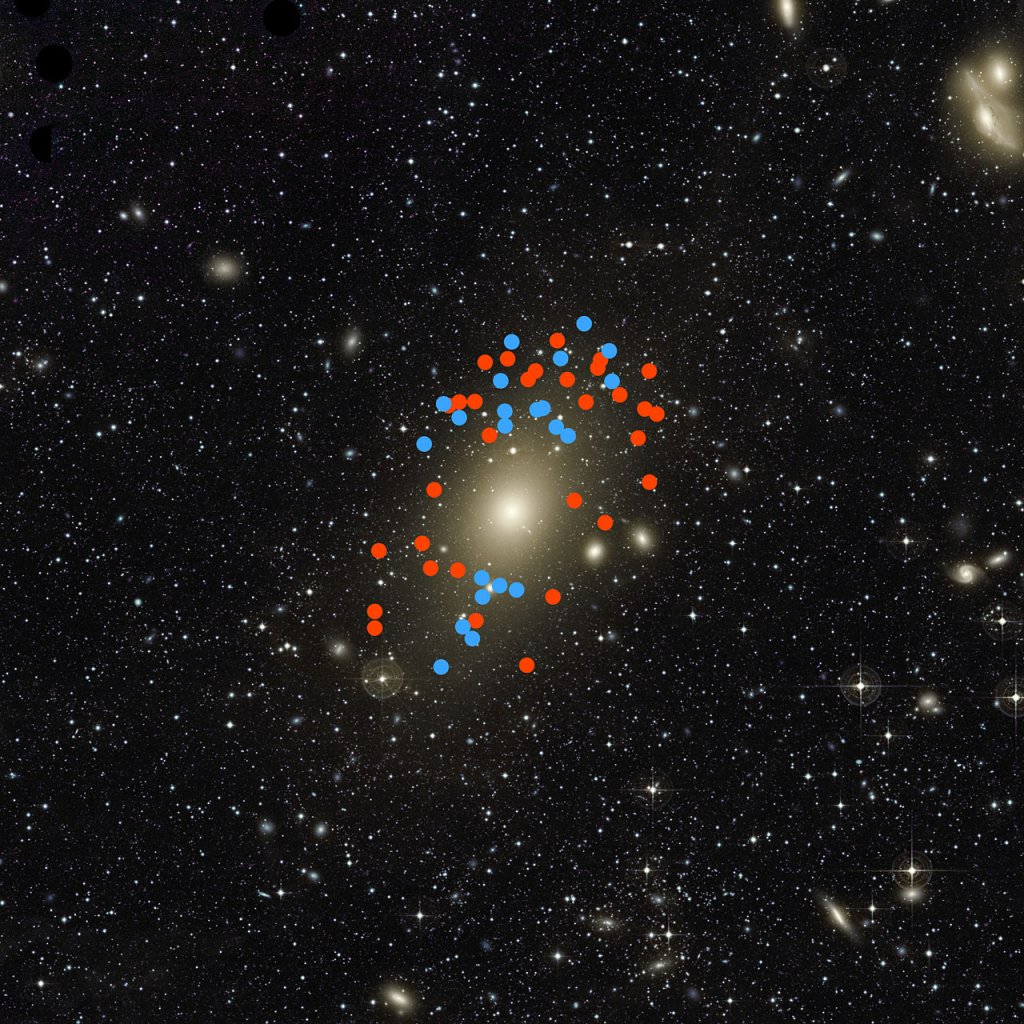

Now, researchers from Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik have identified stars from a galaxy that merged with another member of the Virgo Cluster. Called Messier 87 (or M87 for short), this elliptical galaxy can be found 50 million light-years from Earth in the constellation of Virgo.

Instead of looking for individual stars (which is difficult given the distance between us and M87), this team developed a new approach that centers on planetary nebulae: remnants of Sun-like stars that are no longer fusing hydrogen into helium. Using spectrography, their green color makes them easier to single out than individual stars (it, in turn, can give away the stars’ motion).

Going back to the pond analogy, the researchers expand:

“Just as the water from a glass is not visible once thrown into the pond—but may have caused ripples and other disturbances that can be seen if there are particles of mud in the water—the motions of the planetary nebulae, measured using the FLAMES spectrograph on the Very Large Telescope, provide clues to the past merger.”

“We are witnessing a single recent accretion event where a medium-sized galaxy fell through the centre of Messier 87, and as a consequence of the enormous gravitational tidal forces, its stars are now scattered over a region that is 100 times larger than the original galaxy!” adds Ortwin Gerhard, head of the dynamics group at the Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Garching, Germany, and a co-author of the new study.

[Reference: European Southern Observatory]

Ultimately, while examining light distributions within the outermost part of M87, researchers also found “evidence of extra light coming from the stars in the galaxy that had been pulled in and disrupted,” attributed to the recent formation of a new generation of hot, massive blue-white stars. They suggest that this indicates M87 was spiral prior to it absorbing another galaxy, adding to its overall mass and increasing its gas/dust content.

“It is very exciting to be able to identify stars that have been scattered around hundreds of thousands of light-years in the halo of this galaxy—but still to be able to see from their velocities that they belong to a common structure. The green planetary nebulae are the needles in a haystack of golden stars. But these rare needles hold the clues to what happened to the stars,” notes Magda Arnaboldi (one of the authors from the ESO).

Finally, “This result shows directly that large, luminous structures in the Universe are still growing in a substantial way—galaxies are not finished yet!” says Alessia Longobardi (from Max Planck). “A large sector of Messier 87’s outer halo now appears twice as bright as it would if the collision had not taken place.”