Memory Palace

Forming a memory may be more complicated than scientists first thought.

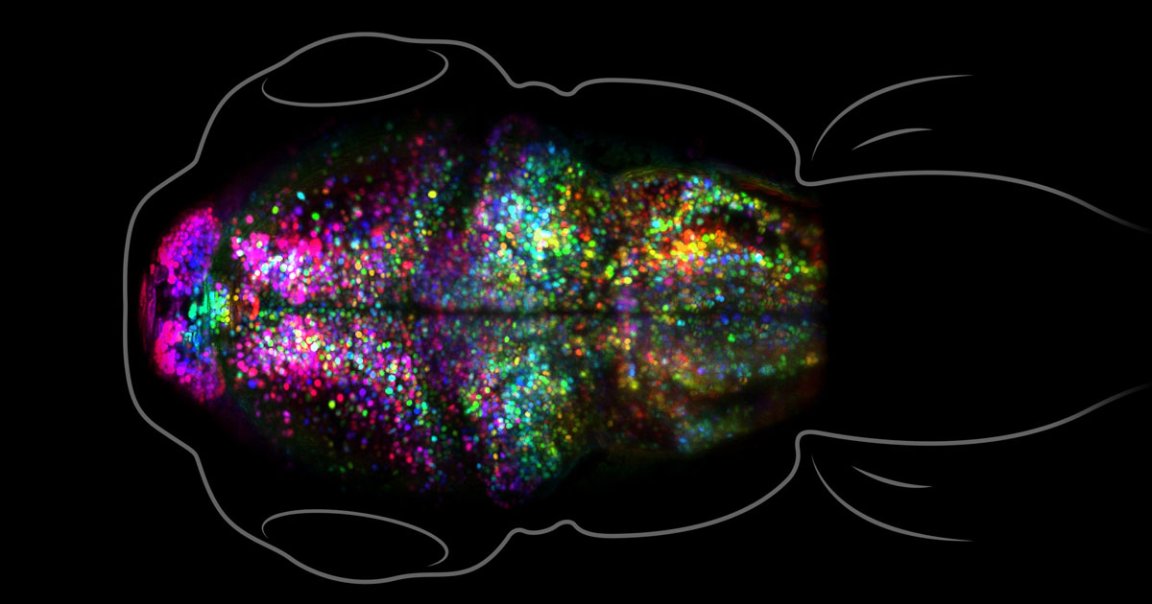

A new report in Quanta Magazine brings context to a study published in January in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The study was led by a team at the University of Southern California who managed to capture images of a memory forming in laboratory fish — in real time, striking. The scientists worked with genetically engineered zebra fish, a species that makes for easy study because they’re naturally transparent in the larval state.

The team expected the brain to restructure its neural pathways slightly, but instead found major development in neural connections, according to Quanta.

“It may be that what we’re looking at is the equivalent of a solid-state drive,” co-author Scott Fraser, a quantitative biologist at USC, told the publication.

Old Heads

To create an observable memory, researchers taught the zebra fish larvae to associate light with being overheated. The zebra fish larvae began trying to swim away when they saw the light, and Fraser’s team imaged the fish before and after to capture the fluorescent markers that were genetically engineered into the fish to highlight its brain activity.

According to Quanta, the type of memory may affect how the brain stores it. Since the memories the USC team created were fearful ones, they may help us better understand why traumatic responses are so debilitating and tough to overcome.

There’s are some shortcomings with the results, though, according to scientists who spoke to Quanta. Considering that zebra fish don’t have an amygdala, the brain’s fear processing center that handles emotional memories, it’s a little difficult to imagine such a complex process will translate easily or succinctly to human brains. If the team really wants to help trauma and PTSD survivors they’ll need to do a lot more testing to understand how different brains work.

“There’s a lot of pruning and synaptic reorganization as a result of experience during development,” Cliff Abraham, a professor of psychology at the University of Otago in New Zealand told the outlet. “If the researchers look at adult zebra fish — which is harder to do because they’re less transparent and have bigger brains — they might get different results.”

More on health developments: Scientists Say They’ve Figured Out How to Grow New Bone Using Sound Waves