Separated from the sun by a vast distance of 3.67 billion miles/5.9 billion km, it’s quite obvious that the dwarf-planet, Pluto, is an incredibly cold world. It’s so cold, in fact, that it has an estimated surface temperature that hangs around -373F (-272C). It’s inconceivable that at such temperatures, one would find anything but a world composed almost entirely of rock and ice. Yet a new paper about Pluto’s largest, equally icy-moon, called Charon, proposes that the system is far more dynamic than previously expected.

New Insights:

Despite having known about Pluto’s existence for the better part of a century, we have yet to obtain any high-resolution images of the dwarf-planet’s surface, or any of its moons either,for that matter, but that’s set to change in the coming year, when the New Horizons spacecraft completes its long journey from the protective confines of Earth, through billions of miles of space, all the way to the most distant reaches of our solar system – where the Plutonian system is – for the very first time. In anticipation of the big day, astronomers have utilized various computer-generated renderings to give us an idea what New Horizons might be in for at its destination.

In the first new revelation this month, astronomers working on behalf of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville published a paper suggesting that we have vastly oversimplified the relationship between Pluto and Charon;it might wind up being much more complicated than astronomers had already surmised.

“How?” you might ask? Well, since Charon’s existence was confirmed some 50 years after Pluto entered the picture, we have uncovered a plethora of strange but intriguing peculiarities about the Moon, especially where its disproportionate size is concerned. As it stands, Charon is approximately 50% smaller than Pluto itself is, which has led scientists to believe that the Pluto-Charon system is closer to a binary planet than a singular planet with several moons.

Simulations show that this assertion might hit the mark, as not only do the objects share a common center of mass (Charon is located just 12,000 miles from Pluto’s center) culminating in the completion of one orbit every 6.4 days, but the two objects are also extremely close together (take the Earth-moon system. for instance. On average, they are separated by 238,855 miles/384,400 km). So close that they might even share the same tenuous atmosphere (made mostly of nitrogen).

Their proximity also results in the strengthening of the tidal forces acting on both objects. On that note;

Looking Back in Time:

Using similar computer-generated renderings, astronomers have deduced the potential existence of cracks scattered about Charon’s surface; cracks that might give us a gander into the evolution of Pluto’s partner-in-crime; perhaps even revealing evidence of an ancient subsurface body of water that was once warmer than you would imagine it to be.

To be more specific:

‘Our model predicts different fracture patterns on the surface of Charon depending on the thickness of its surface ice, the structure of the moon’s interior and how easily it deforms, and how its orbit evolved,’

[Reference: Alyssa Rhoden (From NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center)]

In such a scenario, the constant gravitational interruptions both Charon and Pluto’s s face (and it’s other moons, to a smaller degree) create enough friction to stir their interior and shake up their surface features, leaving cracks behind as a visual reminder of the nature of gravity. Tidal stresses aren’t the only factor to consider either though, its orbit might also a large role, as the eccentricity of its orbit could result in the strengthening of the tidal stresses.

‘Depending on exactly how Charon’s orbit evolved, particularly if it went through a high-eccentricity phase, there may have been enough heat from tidal deformation to maintain liquid water beneath the surface of Charon for some time,’ said Rhoden. ‘Using plausible interior structure models that include an ocean, we found it wouldn’t have taken much eccentricity (less than 0.01) to generate surface fractures like we are seeing on Europa.’

[Reference: Alyssa Rhoden (From NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center)]

Obviously observational evidence is key in gauging the validity of the simulations, but new Horizons will soon give us that. According to Rhoden;

‘By comparing the actual New Horizons observations of Charon to the various predictions, we can see what fits best and discover if Charon could have had a subsurface ocean in its past, driven by high eccentricity.’

[Reference: Alyssa Rhoden (From NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center)]

Not the First:

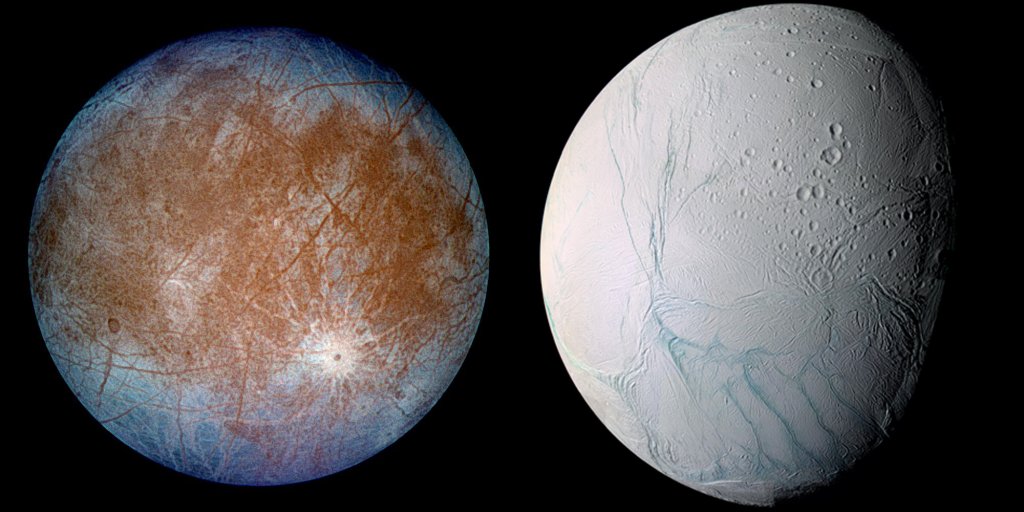

Charon isn’t the natural satellite in our solar system to exhibit these cracks. Two of the most famous examples are Enceladus and Europa. The latter is a moon of Jupiter, while the former belongs to the Saturnian system. Both are believed to be cracked as the result of tidal stresses between the moons and their gargantuan parent planets. In Europa’s case, its fellow Galilean moons – Io, Callisto and Ganymede – help move the process along, while Enceladus is another beast entirely. It has ice volcanoes and the most reflective surface of ANY object in our solar system.

External characteristics aside, both moons are incredibly fascinating to scientists based on what might lurk below their displaced surfaces. You see, the cracks are a symptom of a larger picture; one where these distant worlds go from being completely frozen over and inhospitable, to places where exotic forms of life might thrive within the liquid water far beneath the surface.

Various spacecrafts have made fly-by observations of both moons – be it the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft, or the Galilean spacecraft – but at this point in time, we have neither the technology or the funds to truly explore the environment of either world, but who knows what kind of wonders we might encounter once we do!

In the same vein, it remains to be seen whether or not Charon will meet our expectations once New Horizons finally arrives. One thing is for sure though, it will forever mark history.

The findings were recently published in the journal Icarus.