Plastic Gold

While several companies and institutions have been working at reducing the world’s plastic waste, they are hampered by the lack of means to dispose of them. The most common plastic, polyethylene, happens to also be the hardest to break down. But a solution seems at hand.

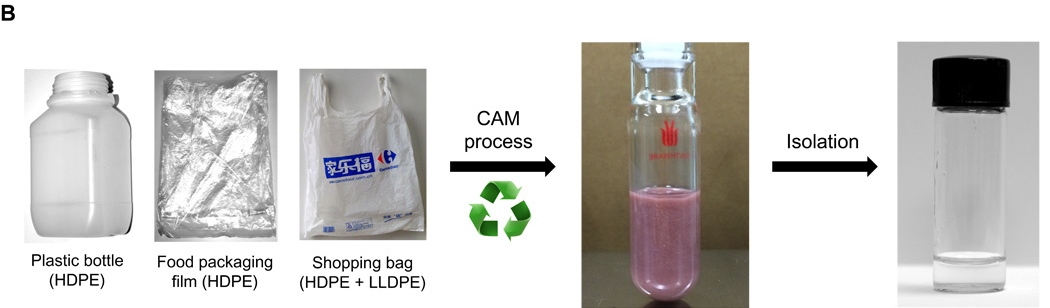

A team of Chinese chemists has developed a method for degrading polyethylene and turning it into a liquid fuel.

Conventional methods to deal with polyethylene include dumping, burning, or pyrolysis, the process of burning it at high temperatures. But pyrolysis has many drawbacks, being energy intensive, polluting, and its byproducts are just as hard to degrade as polyethylene itself.

The study,published in Scientific Advances, details a new approach. The method in the study degrades polyethylene at temperatures as low as 150 degrees Celsius. This method includes adding an organometallic catalyst—a small, commercially available organic molecule-doped with the metal iridium—to the reaction.

The catalyst weakens bonds responsible for polyethylene’s stiff structure, accelerating its breakdown into a liquid product. This liquid product is easier to control and can be used as a diesel fuel. It has been tested on on small samples of plastic bags, bottles, and food packaging.

Concerns

However, there are still obstacles to adoption of the method. The first is scalability. With the burgeoning problem of plastics, the method will have to work on not just grams, but tons.

According to Zheng Huang, project lead, in an interview with Gizmodo, the current process works at a plastic-to-catalyst ratio of roughly 30 to one. But the world will need ten thousand to one, or a million to one, says Huang.

There is also the problem if iridium. It is a rare and precious metal in the platinum family, that needs a cheaper alternative for the method to be adapted.

“We think that the future potential is there—as long as we can improve the efficiency and reduce the cost of the iridium,” Huang said. “Hopefully, very soon we can scale up the process from gram scale in the lab to kilogram and even ton scale.”