Ask virtually anybody in the world what species dominates the Earth, and you will likely hear the common answer: Humans beings. But how do we define our success?

Undeniably, humans are unique among the Earth’s species. Mostly, this is due to the way in which we change our environment to suit us (as opposed to changing to suit our environment). We’ve built massive cities to occupy millions of people, and we harvest immense fields to feed billions. We have philosophical, theological, mathematical, and logical understandings of the world and universe around us. We have a large quantity of very complicated languages, which we use (via technology) to communicate rapidly over long distances and record accurate information. And right now, other members of our species are orbiting above our planet. The list of our accomplishments goes on, and it is quite a resume. Of course, we also have a list of failures and set backs. But today, let’s look at how we managed to so successfully utilize technology and overcome over environment.

Most of our success has been in becoming a technological civilization, but why? There are two major evolutionary factors that contribute to our technological success.

The first is our brain. Humans have one of the highest brain-to-body ratios in the animal kingdom: 1/40. We’re tied with mice, and small birds have a larger brain with a 1/12 ratio. This is likely not, however, a factor in our success. Our brain size appeared on the evolutionary timeline long before we began to use it the way we do today. Also, brain size does not correlate to intelligence. Whales have brains that are simply massive. Yet, that is not reflected in their intelligence.

Of course, the brain is a difficult organ to study in a living subject, so much is left to be understood. However, despite this, we notice that it is our cerebral cortex, and how we use it, that comprises most of what makes our minds unique.

Credit: University of Utah

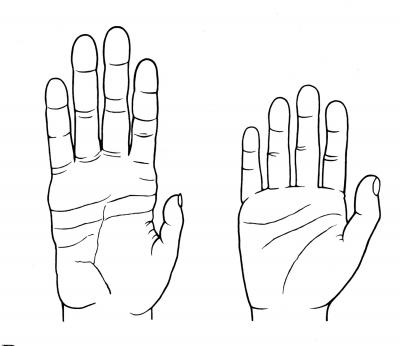

The second factor is our hands. When compared to that of our chimp cousins, our opposable thumbs are much more effective, and our hands are more adapted to the use of tools.

The combination of these two factors allowed us to begin to interact with our environment in a unique way. Our hands initially gave us the ability to adapt to our surroundings, and then we used them to adapt our surroundings to suit us (think permanent shelter and agriculture). It seems obvious that these two traits (complex brain and motor functions) needed one another in order for us to evolve in the way that we did.

Of course, evolution is complex, and a multitude of minuscule factors throughout our timeline could have produced a much different product than the homo sapiens, and many other factors came together to make us into the creatures that we are. Along with other inherited gifts (such as upright posture, long childhood, and endurance), we can be grateful that everything lined up perfectly for us to literally change the face of the Earth.

Credit: wikimedia commons

But this is only a description of our particular features, it does not describe what it means to be an accomplished species. I invite you to try a thought experiment about what it is to be prosperous. We measure ourselves by our intelligence, not only in relation to other species, but in relation to each other. This begs the question of what intelligence is. Intelligence, from a scientific standpoint seems fairly arbitrary, and it is difficult to measure. Qualia provides us with an insurmountable barrier when measuring the understanding of others (for more on quaila, I highly recommend this video from Vsauce.)

So let’s look at another way to measure success: population. Recently, the amount of humans living on Earth surpassed 7 billion, the highest it’s ever been at any one time. But even considering how large the number of people is, we are outnumbered by chickens. The population of domestic chickens around the world is 18.6 billion, more than twice our own. Surpassing both us and chickens is the Euphausia Suberba– Antarctic Krill, with a staggering population of 500 trillion.

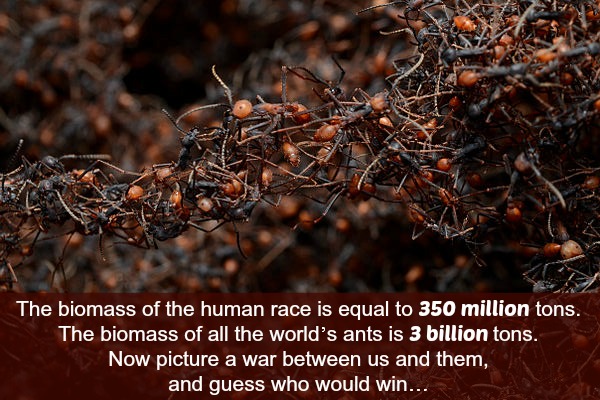

Well okay, but we’re bigger than them, right? Individually, yes, but is our species? The total biomass, the collective weight of the entire human race’s biological material, is 350 million tons. This does beat chickens (40 million tons) and even the krill (150 million tons). We don’t have the largest collective biomass, though. Cattle has a population of only 1.4 billion, but has a biomass of 520 million tons, so one of our own food sources as a species is bigger than us. Surpassing that is ants; however, “ants” include many species. If we took a census of all the ants in the world though we would get 10 billion billion ants. (I hope you don’t mind bugs). And their collective biomass is 3 billion tons; picture a war between us and them. (source)

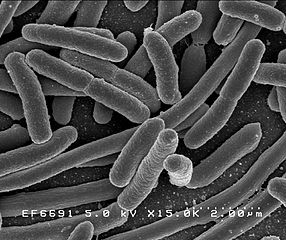

None of these can compare to the biomass of all of the bacteria in the world: 1 million million tons, with a population of 4 quadrillion quadrillion. They dwarf us in population and in biomass. Unfortunately, bacteria are often seen as bad gusy in the animal kingdom, but bacteria are very important. If all the bacteria in the world, most of which is helpful to us, disappeared, so would the rest of life on Earth. There is not a role reversal here.

So humans are unique, but so are all species (in their own way). And we’re also dependent on our fellow creatures for survival. Right now, microbes and bacteria are digesting your food and eating your dead skin, and this is nothing but helpful to you. We have the unique privilege of being able to see the universe in a way that other animals do not see, but instead of putting ourselves on a pedestal, we should see ourselves as part of our natural environment, alongside intricate creatures all with unique contributions to the survival of our mossy home world.