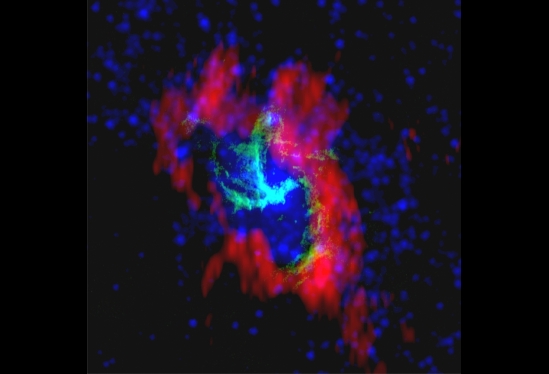

Our quaint Sun lies within the Orion spiral arm of the Milky Way (between the Perseus and Sagittarius arms), about 25,000 light-years from our Galaxy’s central core. Cosmically speaking, 25,000 light-years is a stone’s throw away, but believe it or not, this region is shrouded, figuratively and literally, in mystery. Most of this can be be chalked up to the large concentration of interstellar dust, which traps starlight, packed densely within a tight space. Now, a researcher from the UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Physics (UCSB) has set out to uncover the mysteries hiding in plain site within our galaxy’s central region using good ole astrophotography.

Carl Gwinn, the, who specifically employed the use of Russian RadioAstron spacecraft, looked at several high-resolution images of the targeted region, paying special attention to the compact x-ray source believed to harbor a supermassive black hole, called Sagittarius A*. Despite knowing it has existed for several decades now, astronomers have yet to determine whether the black hole is actively consuming material, or if material is merely being ejected from beyond its event horizon (the point at which all hope of escape is lost). Due to the nature of black holes themselves, we can’t actually stare one directly in the face. Rather, we can infer their existence based on how they affect their surroundings (including gas and dust). Additionally, these objects are also quite vivid non-optically, like at radio, x-ray and infrared wavelengths.

About the Research:

During the original gander at the region’s gas, astronomers saw something that piqued their interest, warranting additional observational time. This gas, importantly, is the only bonafide thing that makes the black hole perceptible optically. “The wavelengths that make Sagittarius A* visible are scattered by interstellar gas along the line of sight in the same way that light is scattered by fog on Earth.”

Gwinn notes, “I was quite surprised to find that the effect of scattering produced images with small lumps in the overall smooth image,” he continued. “We call these substructure. Some previous theories had predicted similar effects in the 1980s, and a quite controversial observation in the 1970s had hinted at their presence.”

Follow-up research was carried out using the Very Long Baseline Array and the 100-meter Green Bank Telescope. They revealed that indeed, there are a number of , for the lack of a better term, faint, gaseous “lumps” photobombing RadioAstron’s view of Sagittarius A*. Gas, in a nutshell, behaves strangely when faced with the crippling effects of the black hole’s gravitational pull. It is twisted and pulled by the sheer force of gravity acting against it. These forces do not typically create blobs of material, but strings (more commonly known as tidal tails when they pertain to galaxies). However, these lumps actually have nothing to do with the relationship between gas and tidal forces, but the nature of scattering itself.

“The theory and observations allow us to make statements about the interstellar gas responsible for the scattering, and about the emission region around the black hole,” one researcher said.

The Ramifications:

These unexpected lumps had additional implications. Specifically, the abnormalities could potentially be used to help derive a more precise weight for this gargantuan object, which is known to contain at least 4 million Suns.

“It turns out that the size of that emission region is only 20 times the diameter of the event horizon as it would be seen from Earth. With additional observations, we can begin to understand the behavior in this extreme environment.”

Furthermore, an even clearer picture can be painted using its scattering patterns. “From these we, can extrapolate those properties to 1 centimeter and use that to make a rough estimate of the size of the source” (Gwinn also notes that he and his team agree with the given estimate). The team’s work also proved useful in validating our ideas of how black hole fluctuations drive the scattering of interstellar gas.

Moving Forward:

All of the new variables will certainly throw embers into the all-but-stagnate firepit that represents the hope of ever fully mapping Sag A*’s emissions, thereby finally putting the age old debate — is Sag A actively consuming material, or is it merely shooting jets of material away from it — to bed for good.

“There are different ways of interpreting observations of the scattering, and we showed that one of them is right and the others are wrong,” said co-investigator Yuri Kovalev, who also happens to be RadioAstron’s project scientist. “This will be important for future research on the gas near this black hole. This work is a good example of the synergy between different modern research infrastructures, technologies and science ideas.”

WATCH: Gas cloud ripped apart by the black hole at Milky Way Center

Until then, a few things still need to be worked out.

“The character of the substructure seems to be random, so we are keen to go back and confirm the statistics of our sample with more data,” Gwinn said. “We’re also interested in looking at shorter wavelengths where we think the emission region may be smaller and we can get closer to the black hole. We may be able to extract more information than just the size of the emission region. We might possibly be able to make a simple image of how matter falls into a black hole or is ejected from it. It would be very exciting to produce such an image.”

Their findings appear in the current issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

This article is listed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. However, FQTQ does not own the rights to the images that are attached.. Learn more about our republishing policy here.