Habitable Worlds

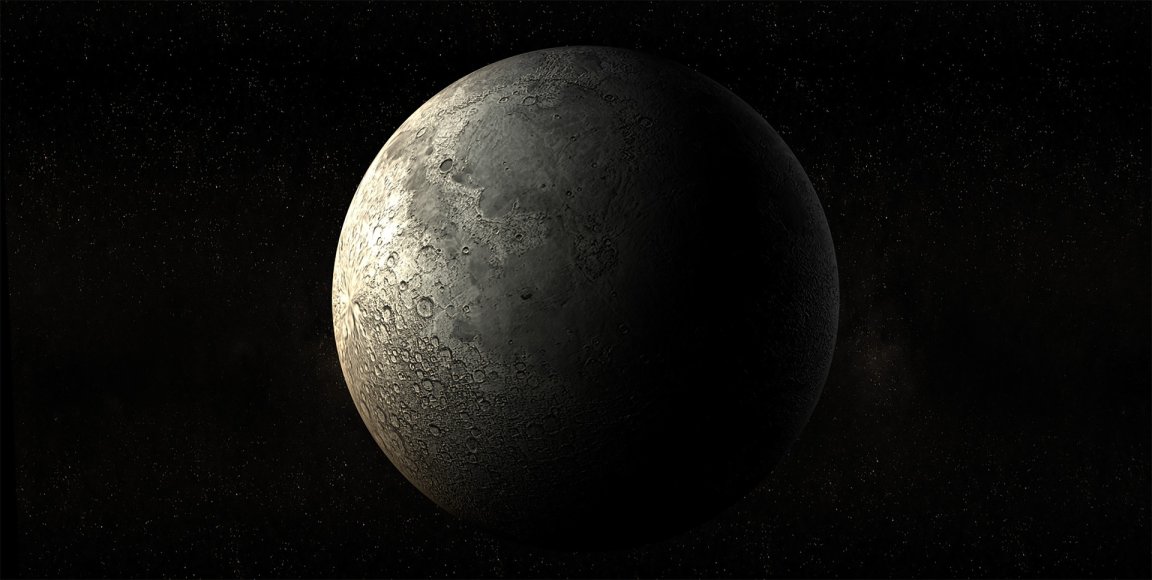

When we think of potentially habitable exoplanets, a clear picture comes to mind: a large, rocky planet orbiting a star at a distance that allows liquid water to exist — ie, something a lot like Earth. However, recent research suggests that habitable qualities could theoretically emerge as a result of moons that are ejected from their system, far from any star.

It is thought that, throughout the universe, there are former moons that were once a part of planetary systems but now wander, rogue and alone. These wandering moons can be flung into the ether when stars are orbited by massive forming planets, which exert a gravitational pull so strong they can eject objects five times as large as Earth or Mars.

A group led by Yu-Cian Hong of New York’s Cornell University and Sean Raymond at the French National Centre for Scientific Research, in Paris, recently ran simulations to test the relationship between newly forming planets and their moons. They found that ex-moons are likely often created in planetary systems that are still in the earlier stages of formation. There is so much chaos in these early systems that it is more likely that moons can be shifted out of place as planets clamor for a stable orbit.

These researchers found that in such chaotic environments, 80 to 90 percent of primordial moons are flung out into interstellar space. Raymond suggested to New Scientist that, for every star in the Milky Way, there could be between 1 and 100 of these rogue moons.

Ex-Moons

However, a graduate student at Columbia University in New York recently added a twist to this story. Alex Teachey, who researches exomoons, has found that moons that are closer to their planets are both more common and stable than those that are farther away. In these strange but surprisingly common circumstances, it is possible for planets and moons to remain tethered as both cosmic objects are hurled together out into space.

We already know that rogue planets are out in our universe — and that they could potentially support life through volcanic activity. Teachey’s work found that having a moon could also help. Because of the chaos of being flung from the system, moons and planets can get close enough to not only become more stable, but to increase tidal heating through gravity. This heating can make wandering moons surprisingly habitable, despite not orbiting a star. In Raymond’s words, “It doesn’t seem like the worst place for life.”

While this is certainly not concluding evidence of life outside of Earth, it opens up an enormous number of less-explored worlds that could have the potential to host life. We’re already planning to explore the potential for life in moons of our own sunny solar system, like Enceladus, Jupiter’s icy ocean-covered satellite. But it seems we also need not look for a star to discover our interstellar neighbors.