The thought of there being science behind the idea of free will seems contradictory, perhaps even oxymoronic, but as science progresses, it delves deeper and deeper into questions that were once only addressed in philosophy or religion. One of them involves free will, which we, as humans, like the existence of. What are we if not completely autonomous? Human history is riddled with struggles to become self-governing individuals, and perhaps this goal is part of the human condition, but our questions still need resolution. So on to the basic question: is “free will, or choice, an illusion?” If only the answer was so simple as a yes or no. The question involves plenty of unknowns, without which, we cannot determine an absolute answer. For example: the nature of human consciousness, the inner-workings of the brain, and the immeasurable external influences on the human form; all these, if better understood, would contribute to our certainty about free will.

We can’t really get an answer out of this, so let’s change the question: can we be confident of our free will, or choice? The answer to this question is almost certainly no. The entirety of science dawned with the philosophy that the universe was predictable and followed a set of rules. Every thing in the universe as we have so far observed follows specific guidelines, and nothing is exempt from the influence of external forces. So why are we – products of the universe – exempt from environmental influence? Free will suggests that we, as an entity, should be able to make decisions free from the external. Certainly external forces play a part, but ultimately the choice is up to us. Right?

Well, Maybe Not:

I’m sure some of you are rolling your eyes right now, scoffing at this, and why wouldn’t you? Intuition tells you that you have free will, and you feel that your choices come from you alone. The reason intuition tells you that you have free will is probably because your mind cannot identify all of the factors affecting your choice, so you default, and conclude the choice came from you.

Time for a thought experiment to illustrate this point. You walk into a bakery, and available for purchase are only two items: there is a tray of chocolate-frosted donuts, and a tray of vanilla-frosted donuts. Let’s assume that you came in here specifically for the task of buying a donut, so the option of not buying a donut is unavailable to us. The choice is simple, it’s one or the other. Still, we must consider the environmental influences at play here. Perhaps you hate chocolate, and have never in your life enjoyed the flavor of chocolate. This factor is well out of your control, you didn’t wake up one day and decide to hate chocolate, you just do.

Same goes for vanilla; what if you choose chocolate instead because vanilla rubs you the wrong way? Maybe one of the trays of donuts looks much fresher than the other, or the frosting more delectable. Perhaps it rained that day and the smell of rain triggers – for whatever reason – a memory of chocolate. Perhaps you are sick to death of vanilla because you had vanilla pudding everyday for lunch this week and if you have any more vanilla flavored substance in your system you just might vomit. Or, maybe you choose the opposite of what you would normally choose, just to spite me and this article. But had you not read this, you wouldn’t feel the need to do that.

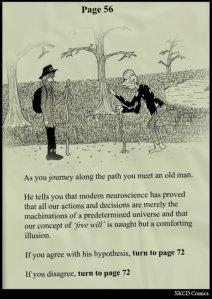

You see what I’m getting at? Many, many factors go into the simplest of choice, factors we may not even think to question, but are very real. Consider this – would you say that an individual cell has free will, or perhaps a microbe? How about a blade of grass, or a tree? How about an ant, a dog, or a chimpanzee in that order? At what point in “complexity” does free will arise? The biologist Anthony Cashmore compares a belief in free will to a belief in magic. Even psychology hinges on the idea that human behavior is predictable. Still, (in terms of how vocal they are) you are more likely to find a scientist against free will and a philosopher for it. They even interpret evidence differently.

Weighing the Evidence:

In a 2008 study, volunteers were asked to push either of two buttons, and their brain activity could predict which button they would push up to ten seconds prior to actually pushing it. Many view this study as a evidence against free will, but no philosopher Alfred Mele, who sees just the opposite. How can we reach a consensus if we don’t even view the evidence the same way? Honestly, we can’t. Not until something more solid shows up.

What we have been talking about is, in the scientific world, called Causal Determinism. Even those in the scientific world have their doubts about determinism.

Physicist Michio Kaku spoke to Big Think about the topic:

What Michio Kaku is talking about in this video is the effect of quantum physics on free will. He talks about how the uncertainty principle keeps us from certainty about an electron’s location. As Stephen Hawking said in A Brief History of Time:

“One certainly cannot predict future events exactly if one cannot even measure the present state of the universe precisely!”

This is true (and why physicists hate quantum mechanics so much.) How can determinism be true if we can’t measure certain states of the universe as it currently exists? And the question remains; how do we know that electrons have any bearing on the free will? We don’t. The alternative is that our actions are completely and totally random. If everything is random chaos, do we still have choice?

Carlo Rovelli proposes an experiment (albeit, an impossible one), in which a subject is placed in a situation, possibly one of danger, where all of the factors leading up to their choice are the same; their mental state, mood, memories, etc. Accounting for all of the factors would be tedious and probably impossible, but if we could repeat this experiment, and see what choice they make. Observing the choices made in a similar (but I will repeat, impossible and hypothetical) experiment could tell us something about free will.

In Short:

We don’t know, and we may never know whether or not free will exists. There are so many unanswered questions, and so many factors to consider. Keep thinking about it, and who knows, maybe one of you can solve the great free will debate.