If we ever hope to leave the Earth, we will obviously need to have a destination in mind. Currently, the most likely candidate for colonization is Mars; however, this world isn’t exactly Earth-like. Ultimately, this dry and dusty world would make habitability exceedingly difficult (if not downright impossible). With the right technology, we may be able to establish long-term colonies, but it would be far better if we could find a world that is a bit more like our own.

Finding Earth’s Twin

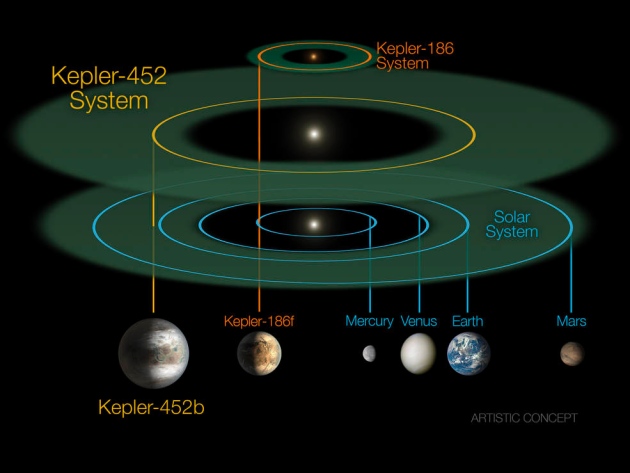

To date, the most Earth-like planet that we’ve discovered is Kepler 452b. It has an orbit that is 385 days long, which is remarkably close to our own 365 day year. Its sun is also nearly the same size as our own (both are classified as “yellow dwarfs”), and it falls in almost the exact same place as the Earth does in our own solar system.

However, the planet is five times as massive as the Earth (nearly 60% larger). That sounds like a lot, but keep in mind that a vast majority of the planets that we’ve discovered are “hot Jupiters,” supermassive planets that orbit remarkable close to their parent stars. Thus, in the grand scheme of things, the size of Kepler 452b is rather similar to Earth’s. Yet, the size does spell bad things for us. With a gravity that it twice as strong, it would be hard to adapt to live on this planet.

True, this size means that the planet is likely a rocky world (this is a very good thing, as we really don’t want to try and live on a gas giant), but the planet’s sun, Kepler 452, is a little older than our own. As a result, it has a higher energy output. So in the end, the planet receives about 10% more energy than the Earth does.

That also spells bad things for habitability.

So. That’s it. The most Earth-like planet is, in reality, not too Earth-like. At least, it’s unEarth-like enough that habitability would be a significant problem (of course, it would take us well over 26 million years to get there, so habitability may be the least of our concerns).

However, space is big. Given its sheer immensity, there should be a number of other earth-like planets out there, yes?

Well, based on information from the Kepler survey, scientists predict that there are around 1 billion Earth-sized worlds in the Milky Way galaxy alone. And there are some 100 billion galaxies in the observable universe, meaning that there are literally trillions of (at least somewhat) Earth-like planets out there.

And the numbers just got even more exciting. According to new data from the Hubble Space Telescope and the Kepler Space Observatory, 92% of Earth-like planets haven’t been born yet.

In essence, the data reveals that, while star birth is happening at a much slower rate than what it was previously, there is enough material left in our cosmos that the universe will be able to produce a plethora of new stars and planets.

As co-investigator Molly Peeples states, “There is enough remaining material to produce even more planets in the future, in the Milky Way and beyond.”

So it seems that our planet sprang up rather early in the game. According to the study, when our solar system was born, there existed just eight percent of the potentially habitable planets our universe (hence, where the “92% have yet to be born” comes from).

It is comforting to know that the difficulties that we’ve encountered finding Earth-like planets (and alien life) may not be due to our own failings, but be because the worlds simply don’t exist yet. Perhaps, they are on their way.

And although the universe may be lonely, ultimately, our early birth has proven to be invaluable to our understanding of the universe.

As NASA notes, “A big advantage to our civilization arising early in the evolution of the universe is our being able to use powerful telescopes like Hubble to trace our lineage….the observational evidence for the big bang and cosmic evolution, encoded in light and other electromagnetic radiation, will be all but erased away 1 trillion years from now due to the runaway expansion of space. Any far-future civilizations that might arise will be largely clueless as to how or if the universe began and evolved.”

The results will appear in the October 20 Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.