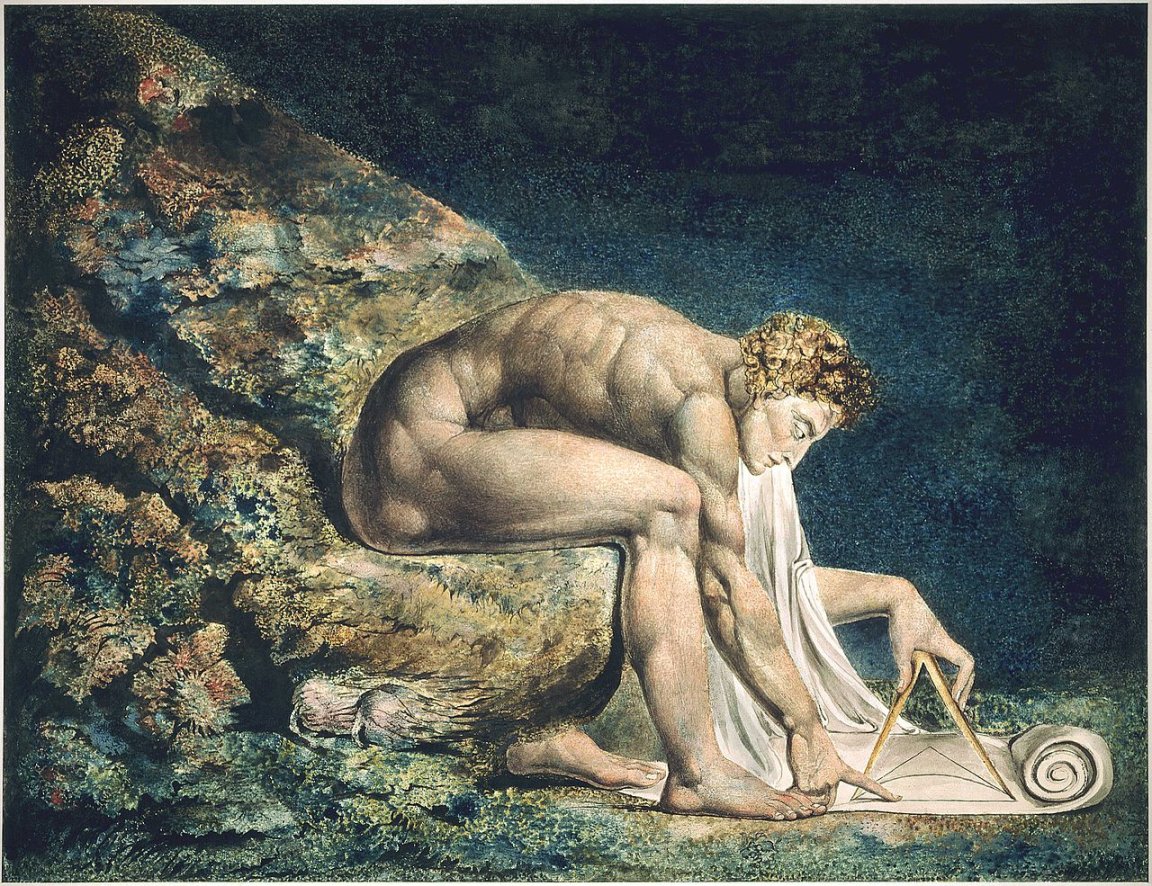

In his painting ‘Newton’, the British poet and painter, William Blake, represents Newton as a divine geometer. He is sitting naked on a rock at the bottom of the ocean leaning over a scroll, and measuring the symbol of the Trinity.

Blake’s depiction of Newton’s persona is symbolic, but it is closer to the real Newton than any other artistic rendition. Much of what we know about Newton is based on his extraordinary contributions to science such as the three major laws of motion (the principles of inertia, force, action and reaction), the law of gravitation, and his discoveries in optics, astronomy, and mathematics. Newton’s laws enabled measurements of actual distances, speeds, and weights to be calculated, laying the foundation of modern inventions from the steam engine to the space rocket. In large part because of Newton, the empirical approach, based on the rule that you must try out ideas by testing them, became the norm.

However, there is a part of Newton’s life that is less talked about, the part that concerns his character and its connection to his discoveries.

Newton’s biography is a catalog of the symptoms of bipolar (or manic depressive) disorder, an illness he suffered from most of his life. Romantic writers often called manic depression ‘a disease of men of genius’, while others considered it an essential element for creativity. It was argued that depression made one a perfectionist and mania led to intense periods of productivity, faith in ones own talent, and the need to prove oneself right.

This may be partly true, but no matter how many creative inspirations one gets from the manic state and how extraordinary the achievements are as a result of it, one thing is clear to all who suffer from it – this is an illness that can destroy lives and cause tremendous pain for all connected to the sufferer.

Newton exhibited signs of bipolar disorder early in life; he was a solitary child who didn’t engage in games with other children. He spent most of his time alone, building miniature mills, machines, carts, and other inventions. He was high strung, egotistical, and dominant. He experienced attacks of rage, which he directed toward his friends and family. He later recalled ‘threatening my father and mother to burn them and the house over them.’

Newton also had intense moments of remorse, when he made long lists of his ‘sins’ or wrongdoings. His list recorded ‘striking many’, ‘punching my sister’, ‘peevishness with my mother’. His violent temper made him unpopular and his peers and the servants rejoiced when Newton left home for Cambridge.

At Cambridge, Newton made only one friend among his fellow students. His notebooks on his college years document anxiety, sadness, fear, a low opinion of himself, and suicidal thoughts.

After his appointment as Fellow of the University in Cambridge, Newton continued to have manic episodes, often forgetting to eat. Such events were usually followed by a collapse into depression, and he would become enraged by any criticism of his work. As a result, he would withdraw from the scientific community and refuse to continue his research.

Despite his success and recognition, Newton was afraid to expose his work to the criticism of fellow scientists. He kept his calculus secret until Leibniz made a claim of discovering it first. And if it wasn’t for his astronomer-friend, Edmund Halley’s encouragement, he probably wouldn’t have published his most important work, the Principia.

Newton avoided the company of others. When he had to interact with people, he contributed little to conversations. His relationships with other scientists were tyrannical. He would refuse to speak to those who dared to disagree with him. Newton sought quarrels with friends and foes alike.

There were two people in Newton’s life whom he loved. One was his niece, Catherine Barton, who became her uncle’s housekeeper in London, and the other was a Swiss mathematician – Fatio de Duillier, who was only 25 years old when he met Newton. Because of the great emotional intensity of their relationship, and the fact that neither man ever married, some of Newton’s biographers suspect their relationship was homosexual in nature, but there is no proof.

Newton had a strong aversion to fame and requested that his papers be published anonymously. This is what Jane Jakeman writes about Newton’s tendency for secrecy and anonymity in her book ‘Newton’:

‘In 1696 Leibniz and a Swiss mathematician, Johann Bernoulli, set up a mathematical problem as a challenge to any European mathematician to try to solve. Other famous mathematicians were unable to even come near an answer. Newton was sent the problem when he was in the throes of his busiest time at the Mint and came home exhausted from a hard day’s work. But he had solved it by four o’clock the following morning. He published the answer anonymously, but Bernoulli guessed who had solved it: he said that he recognized ‘the lion by its claw.’

At times of depression, Newton hallucinated and had conversations with absent people. He became obsessed with religion and immersed himself in alchemy. He spent 25 years in the study of alchemy in secret, searching for mysterious elixirs and writing thousands of pages on the subject.

Like many people with bipolar disorder, Newton developed grandiose delusions. In his notes on alchemy and religion he wrote that he was appointed by God to bring His truth to the world.

The scientific truths that Newton uncovered during his lifetime have raised him to demigod status, but it was at a price. He suffered immense pain and torment due to his mental disorder. William Blake wrote, ‘Without contraries [there] is no progression. Attraction and repulsion, reason and energy, love and hate, are necessary to human existence.’ This reminds us that the great Sir Isaac Newton was human too.