Jupiter’s moon, Europa, has long fascinated scientists. They believe it’s covered in a massive salty ocean, holding almost twice as much water as all of Earth’s oceans combined, making it one of the best places to look for extraterrestrial life in our solar system — but covered by a formidable icy shell.

Now, NASA Jet Propulsion Lab scientists —drawing on data from the agency’s Juno mission, which performed a flyby of Europa in 2022 — have determined that this particularly heavenly body is seriously thick, measuring an average of 18 miles in the region observed by the spacecraft.

It’s the first time we’ve been able to hone in on a specific measurement. Previous estimates have ranged from half a mile to tens of miles, highlighting how much there’s still to learn about Jupiter’s icy moon.

The estimated thickness of the shell could also have major implications for future efforts to study Europa’s habitability. For one, nutrients and other building blocks like oxygen would have a very long way to travel.

“If an inner, slightly warmer convective layer also exists, which is possible, the total ice shell thickness would be even greater,” said Juno project scientist and co-investigator Steve Levin, coauthor of a paper published last month in the journal Nature Astronomy, in a statement. “If the ice shell contains a modest amount of dissolved salt, as suggested by some models, then our estimate of the shell thickness would be reduced by about three miles.”

Even more intriguingly, the scientists suggested in their paper that the “ice shell may contain subsurface cracks, faults, pores or bubbles,” which could “provide pathways for habitability by facilitating the transport of oxygen and nutrients between the surface and the ocean.”

After examining data from Juno’s microwave radiometer, the team found evidence of the “presence of cracks, pores or other scatterers extending to depths of hundreds of metres below the surface,” supporting the tantalizing hypothesis.

These cracks, they suggest, may only measure a few inches across, but they could extend hundreds of feet below the moon’s surface.

Nonetheless, that would still make them a poor pathway for oxygen and nutrients.

“How thick the ice shell is and the existence of cracks or pores within the ice shell are part of the complex puzzle for understanding Europa’s potential habitability,” said Juno principal investigator and Southwest Research Institute scientist Scott Bolton in the statement.

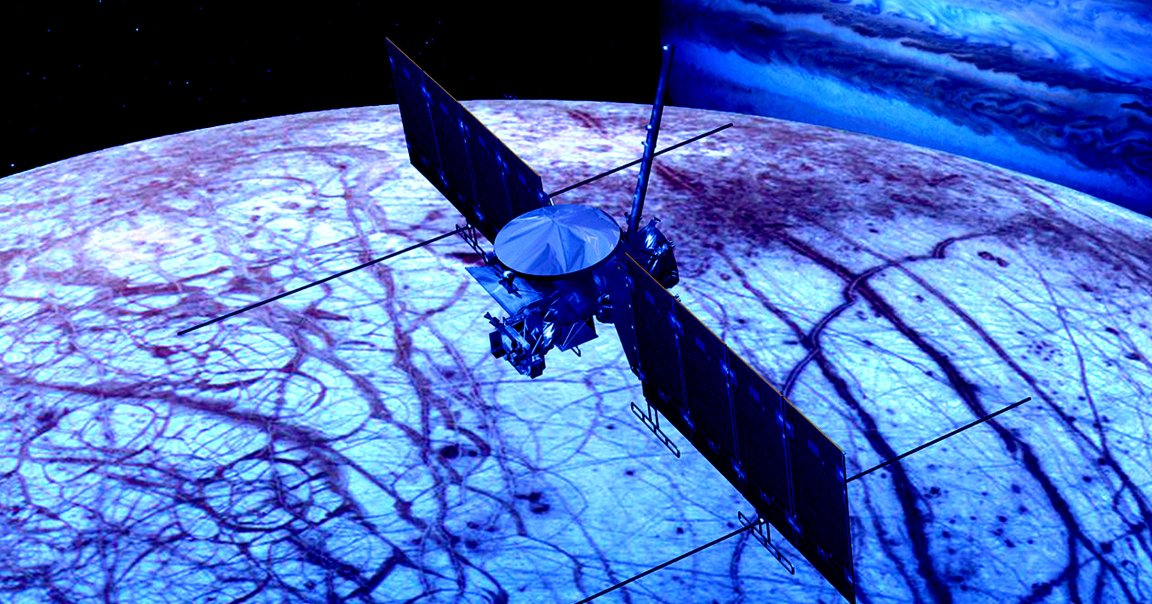

Fortunately, we’re already planning to have another look with the help of NASA’s Europa Clipper and the European Space Agency’s Juice (JUpiter ICy moons Explorer) spacecraft, both of which are already on their way to Jupiter and its enormous system of almost 100 known moons. The Europa Clipper is expected to arrive at Jupiter in 2030, and will then attempt to conduct almost 50 flybys of Europa. The ESA’s counterpart, on the other hand, is expected to arrive in 2031.

Perhaps then we can have another glimpse of Europa’s thicker-than-a-bowl-of-oatmeal crust.

More on Europa: Scientists Intrigued by Large Spider-Like Blob on Europa