One of the trickiest parts of tracking the COVID-19 pandemic is how good the coronavirus is as hiding out undetected in the human body.

In some cases, it can take as many as five days for people infected by the coronavirus to start showing symptoms. During that time, they could be further spreading the disease to new people, without realizing that they themselves are sick.

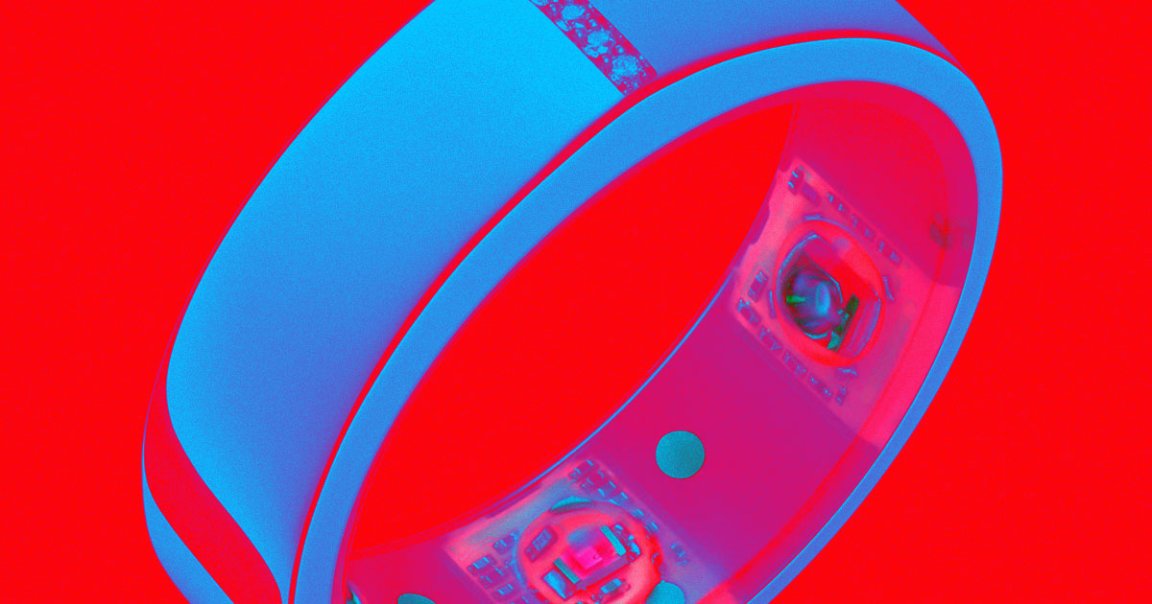

One team of scientists and doctors is trying to detect the disease earlier than ever before, by examining data recorded by a wearable smart ring that they say they can spot a budding COVID-19 case before noticeable symptoms begin.

“There’s a large number of people out there, whether they’re on the front lines, wherever that is, that have this and they don’t know about it,” Dr. Ali Rezai told Futurism.

“Subjects wear the ring, they get our app, they get a questionnaire in the morning,” Rezai added. “Five minutes in the morning, they play some games. It’s a gamified app. We’re asking content-specific questions for COVID.”

Rezai, who’s leading the new project, is a neurosurgeon at West Virginia University Medicine and the head of the WVU Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute. He and his team partnered with the wearable company Oura Health, which manufactures a smart ring that constantly records temperature, sleep patterns, activity levels, and heart rate variability.

By training an artificial intelligence algorithm with all of that data — collected from tens of thousands of users and sorted by whether subjects were shown to be infected by coronavirus-detecting nasal swabs — Rezai says he’s already seeing clear correlations between changes in temperature and the onset of COVID-19.

Right now, his team is running a trial in which about 1,000 doctors, nurses, and other hospital workers on the front lines constantly monitor their biometrics by wearing an Oura ring and logging cognitive and psychological data on an accompanying app.

So far, Rezai says his AI model can predict a case 24 hours in advance 90 percent of the time, and with more data he hopes to add an extra day or two of the warning time.

“The goal is to use the Oura technology and our framework and app to predict the onset of symptoms and identify frontline healthcare workers before they become symptomatic,” Rezai said, “and limit the spread.”

Oura Health CEO Harpreet Rai told Futurism he’s heard from customers who were warned by their rings that they were developing a flu or would have a fever in the next two days, laughed it off, and then found themselves bedridden right around when the ring predicted.

One Oura Ring user wrote an extensive account on Facebook about how his ring warned him that he was likely going to be sick soon based on fluctuations in his temperature. He went and got a nasal swab test for COVID-19, which came back positive, and he was able to quarantine sooner than if he had waited for the telltale flu-like symptoms to begin.

But aside from users occasionally reaching out to share their biometric data, Rai says Oura, as a company, doesn’t typically conduct research studies and isn’t involved in the day-to-day of the ongoing COVID-19 project

“What you’ll see with independent companies is you can pick and choose your data, and that ends up being biased,” Rai said. “So that’s why we think it’s important to partner with academics, to really make sure there’s a good scientific process in place.”

It’s difficult to reckon with the privacy implications of constant biometric monitoring like what can be done with Oura’s smart ring. But aggressive monitoring with voluntary, active participation may be necessary to finally kick this pandemic, according to Brown University epidemiologist and surgery professor Dr. Simin Liu, who’s unaffiliated with the Oura and WVU study.

“The idea of syndromic surveillance using wearable such as this one has been around for some time,” Liu told Futurism. “To improve precision medicine and public health, we do need more work and data concerning the validity and cost-effectiveness of these new technologies.”

He pointed toward research and an editorial published Friday in the journal JAMA arguing that because there are no known pharmaceuticals to treat COVID-19, public health experts are left exploring non-pharmaceutical interventions like surveillance and quarantines. Many of these techniques, he said, have been deployed in China, especially Wuhan, to prevent a resurgence of the coronavirus.

“In my view, active surveillance is definitely the future when these types of wearables will be integrated simply as a way of life,” Liu added, “particularly for those of us who live in an open society.”

Until we have a vaccine, Rezai told Futurism, COVID-19 isn’t going to go away for good. In the meantime, he feels it’s crucial to develop tools that will keep people safe. Technological interventions, whether it’s data from a wearable or updates from an app, will be an essential part of that.

“There is no one silver bullet. That’s something I’ll just say. I think we all need to talk together to solve a pandemic like this,” Oura CEO Rai told Futurism. “I do think wearable data, biometric data from wearables as a whole is valuable as a warning sign. We’re excited to do our part.”