An international team of researchers analyzing decades of observations from many facilities, including NASA’s Swift satellite, the W. M. Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea and the Pan-STARRS1 telescope on Haleakala, has discovered an object in space called SDSS1133, that might be a black hole catapulted out of a galaxy. Or it might be a giant star that is exploding over an exceptionally long period of several decades. In any case, one thing is certain: this mysterious object is something quite unique, a source of fascination for physicists the world over because of its potential to provide experimental confirmation of the much-discussed gravitational waves predicted by Albert Einstein.

“With the data we have in hand, we can’t yet distinguish between these two scenarios,” said lead researcher Michael Koss, an astronomer at ETH Zurich, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. “One exciting discovery made with NASA’s Swift is that the brightness of SDSS1133 has changed little in optical or ultraviolet light for a decade, which is not something typically seen in a young supernova remnant.” The study will be published in the Nov. 21 edition of Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

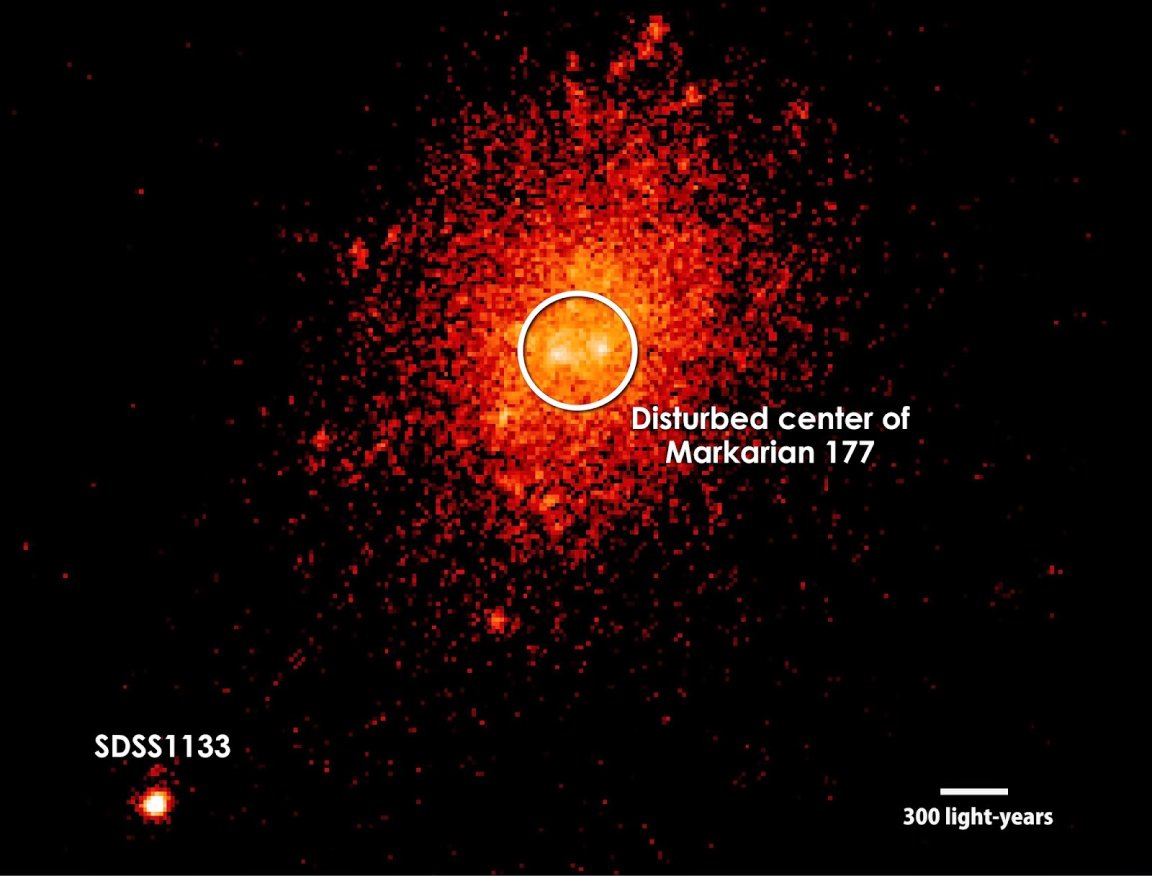

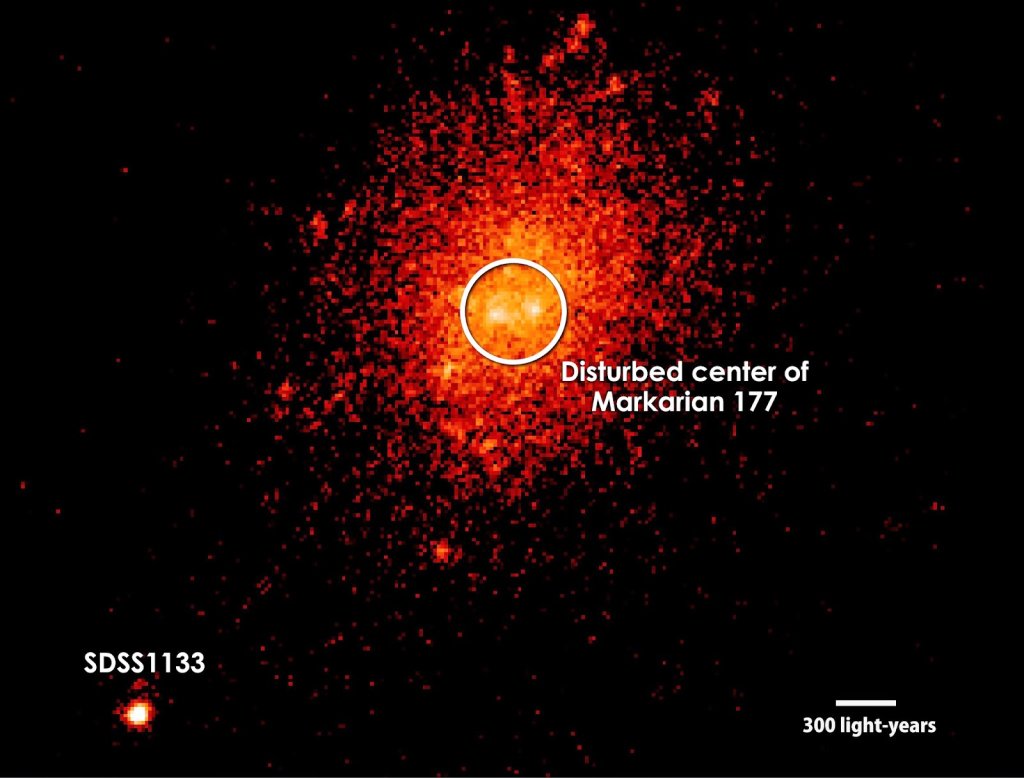

The mystery object is part of the dwarf galaxy Markarian 177, located in the bowl of the Big Dipper, a well-known star pattern within the constellation Ursa Major. Although supermassive black holes usually occupy galactic centers, SDSS1133 is located at least 2,600 light-years from its host galaxy’s core. The team was able to detect it in astronomical surveys dating back more than 60 years.

The researchers first realized that SDSS1133 was a unique object last year, while observing it with a reflecting telescope at the Keck Observatory in Hawaii. Comparisons with an astronomical map from 2001 showed that it was already ten times weaker last year than in 2001 – and although the object was visible on maps from the 1950s and 1990s, it could only be seen very weakly. SDSS1133 shone very brightly in 2001 but did not go completely dark afterwards, which showed that it cannot be a normal supernova – the life-ending explosion of a star – because supernovae tend to be detectable for only a few months before fading significantly.

“When we analyzed the Keck data, we found the emitting region of SDSS1133 is less than 40 light-years across, and that the center of Markarian 177 shows evidence of intense star formation and other features indicating a recent disturbance that matched what we expected for a recoiling black hole,” said Chao-Ling Hung, a University of Hawaii (UH) at Manoa graduate student performing the analysis of the Keck Observatory imaging in the study.

From a comparison of the wavelength spectrum of the light emitted by SDSS1133 and a nearby dwarf galaxy the scientists concluded that the object might be a black hole that belonged to this dwarf galaxy at one stage and was jettisoned out of it.

And yet the researchers are far from certain, mainly because there is a second, more exotic possibility: SDSS1133 could be a new type of long-duration outburst before a supernova within a giant star. This giant star would have lost much of its mass in a series of eruptions over the course of at least 50 years before its final explosion.

“We suspect we’re seeing the aftermath of a merger of two small galaxies and their central black holes,” said co-author Laura Blecha, an Einstein Fellow in the University of Maryland’s Department of Astronomy and a leading theorist in simulating recoils, or “kicks,” in merging black holes. “Astronomers searching for recoiling black holes have been unable to confirm a detection, so finding even one of these sources would be a major discovery.”

Scientists have already observed stars changing in this fashion: Eta Carinae, one of the most massive stars in our own galaxy, briefly became the second-brightest star in the sky in 1843. If this type of activity were also the explanation for SDSS1133, that would make it the longest continuous outbursts ever observed before a supernova.

Merging black holes release a large amount of energy in the form of gravitational radiation, a consequence of Einstein’s theory of gravity. Waves in the fabric of space-time ripple outward in all directions from accelerating masses. If both black holes have equal masses and spins, their merger emits gravitational waves uniformly in all directions. More likely, the black hole masses and spins will be different, leading to lopsided gravitational wave emission that launches the black hole in the opposite direction.

To analyze the object in greater detail, the team is planning ultraviolet observations with the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph aboard the Hubble Space Telescope in October 2015. “We found in the Pan-STARRS1 imaging that SDSS1133 has been getting significantly brighter at visible wavelengths over the last 6 months and that bolstered the black hole interpretation and our case to study SDSS1133 now with HST,” said Yanxia Li a UH Manoa graduate student involved in the analysis of the Pan-STARRS1 imaging in the study.

If SDSS1133 isn’t a black hole, then it must have been a very unusual type of star known as a Luminous Blue Variable (LBV). These stars undergo episodic eruptions that cast large amounts of mass into space long before they explode. Interpreted in this way, SDSS1133 would represent the longest period of LBV eruptions ever observed, followed by a terminal supernova explosion whose light reached Earth in 2001.

For an LBV to explain SDSS1133, the star must have been in nearly continual eruption from at least 1950 to 2001, when it reached peak brightness and went supernova. The spatial resolution and sensitivity of telescopes prior to 1950 were insufficient to detect the source. But if this was an LBV eruption, the current record already shows it to be the longest and most persistent one ever observed. An interaction between the ejected gas and the explosion’s blast wave could explain the object’s steady brightness in the ultraviolet.

“Dwarf galaxies are very common,” said Koss. “Therefore it would be highly probable that other recoil events would appear before too long. The hope is that we would be able to observe one near Earth and measure the gravitational waves.”

Whether it’s a rogue supermassive black hole or the closing act of a rare star, it seems astronomers have never seen the likes of SDSS1133 before.

Provided by NASA, ethz.ch, keckobservatory.org