Turning Mice into Hulks

Traditionally, mice are the hunted animal. But scientists have discovered that by just pushing the right buttons in the brain, it’s possible to turn these meek mice into aggressive predators. This is what a team of scientists from Yale University were able to accomplish. They detail their work in a paper published in the journal Cell. The study gives us a glimpse into how predatory/hunting behavior has evolved over hundreds of millions of years.

The secret is in two sets of neurons found in the brain’s amygdala, which is the part that controls motivation and emotion. When these two sets of neurons were activated in mice using optogenetics — i.e., light stimulation — by shining a laser into them, the team observed changes in the behavior of the mice.

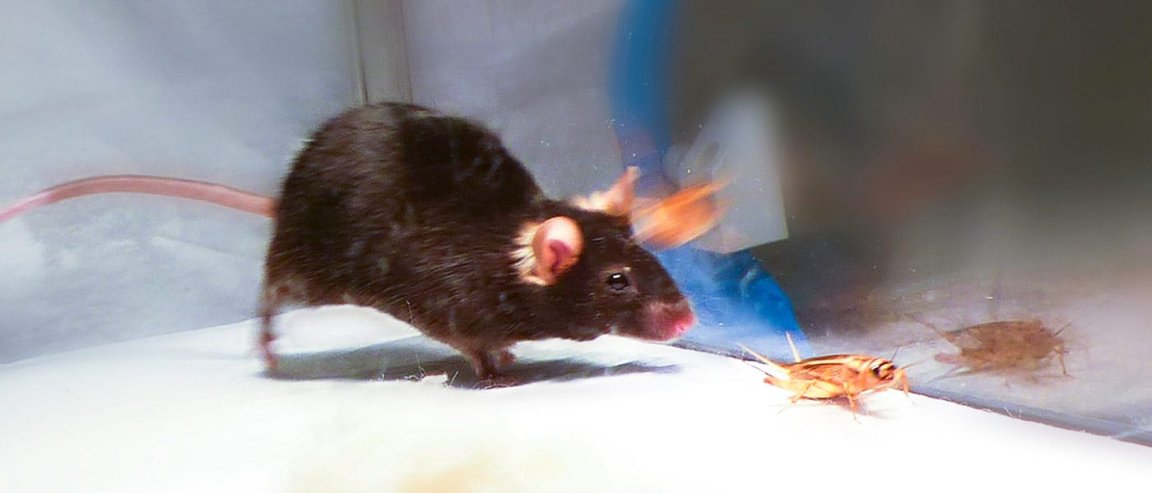

Specifically, it turned the mice aggressively predatory, with increased use of its jaw and neck muscles to bite anything on their path. It’s like they got furious, snapping even at innocuous objects like stick, bottle caps, and toys. Additionally, the hungrier the mice were, the more aggressive their behavior became. Except, they didn’t attack other mice, which was rather curious. When the laser light is off, the mice went back to normal behavior.

“The animals become very efficient in hunting,” explained researcher Ivan de Araujo, a Yale University associate professor of psychiatry and an associate fellow at The John B. Pierce Laboratory in New Haven. “They pursue the prey [a live cricket] faster, and they are more capable of capturing and killing it,” De Araujo said.

Brain Kill Switch

This aggressive behavior triggered by these activated neurons, however, seems to be reserved only for prey. The researchers take this as a clue that could explain how predatory behavior evolved some millions of years ago. The development of hunting circuits that coordinate how a predator’s jaw and neck muscles move is one thing, and it all “must have influenced the way the brain is wired up in a major way,” De Araujo said. “This is a very complex and demanding task.”

Before the experiment, the researchers already expected to find these circuits in mice, because there is inherent predatory behavior in them, usually in attacking insects or — in the case of the killer mouse — eating live prey, even other mice. That’s when they stumbled upon the two sets of neurons in the amygdala.

“When we stimulate [both sets of] neurons it is as if there is a prey in front of the animal,” De Araujo explained. “They assume the body posture and actions usually associated with real hunting.”

This is a peek at the complexity of the brain, and some say that these same hunting instincts are found in other species, including humans. It seems that the brain’s circuitry can be turned on and off to activate particular behaviors. Clearly, a great deal more of research is needed to explore the possibilities this kind of knowledge possesses.