In a staggering find, scientists recently announced that the quasar closest to Earth is powered by two, not one, supermassive black holes.

The quasar in question lives in a galaxy dubbed Markarian 231 (Mrk 231). And although Mrk231 is the closest galaxy to Earth that hosts a known quasar, it is still rather far away, orbiting through the cosmos some 600 million light-years from our solar system.

Quasars, or “quasi-stellar radio sources” are the brightest and most distant star-like objects in the known universe. In fact, they are so bright, and they emit so much energy, some of them are believed to be producing 10 to 100 times more energy than the entire Milky Way Galaxy, and they do so in an area that’s comparable to the size of our solar system.

Imagine the energy of an entire galaxy squeezed down to a size that is equivalent to our Sun’s sphere of influence, and you will begin to understand the amazing power of a quasar.

Now, it’s generally agreed upon that quasars are produced by supermassive black holes consuming matter (perhaps devouring the equivalent mass of ten suns per year?) in an accretion disk. As the matter spins faster and faster, it heats up. Thus, giving off massive amounts of light and other forms of radiation such as x-rays, light rays, gamma rays and radio waves. This is essentially what we believe quasars are.

However, their exact mechanisms aren’t fully understood (aka, we don’t know exactly what they are).

As such, the discovery of these two black holes, which are furiously whirling about one another, indicates that, perhaps, most quasars host two central supermassive black holes. “The structure of our universe, such as those giant galaxies and clusters of galaxies, grows by merging smaller systems into larger ones, and binary black holes are natural consequences of these mergers of galaxies,” said co-investigator Xinyu Dai of the University of Oklahoma.

Thus, it is believed that these amazingly powerful objects come to orbit each other as a result of the most cataclysmic events in the known universe—galactic mergers.

Although such mergers rarely result in stellar collisions, as stars are amazingly far from one another, analyses suggest that the supermassive black holes that are generally found in the center of galaxies slowly come together as galaxies collide.

The result of such a merger?

Thanks to this research, we now have a better idea. It seems that, as they spiral in, the black-hole duo creates a tremendous amounts of energy. Ultimately, the amount of energy that is produced is so great, the core of the galaxy outshines the rest of the galaxy, meaning that this small region of space is brighter than the billions and billions of stars that makeup the rest of the galaxy, and it is this staggering amount of energy that we define as “quasars.”

In other words, black hole duos might be the mechanisms behind quasars a majority of the time.

The results were published in the August 14, 2015 edition of The Astrophysical Journal.

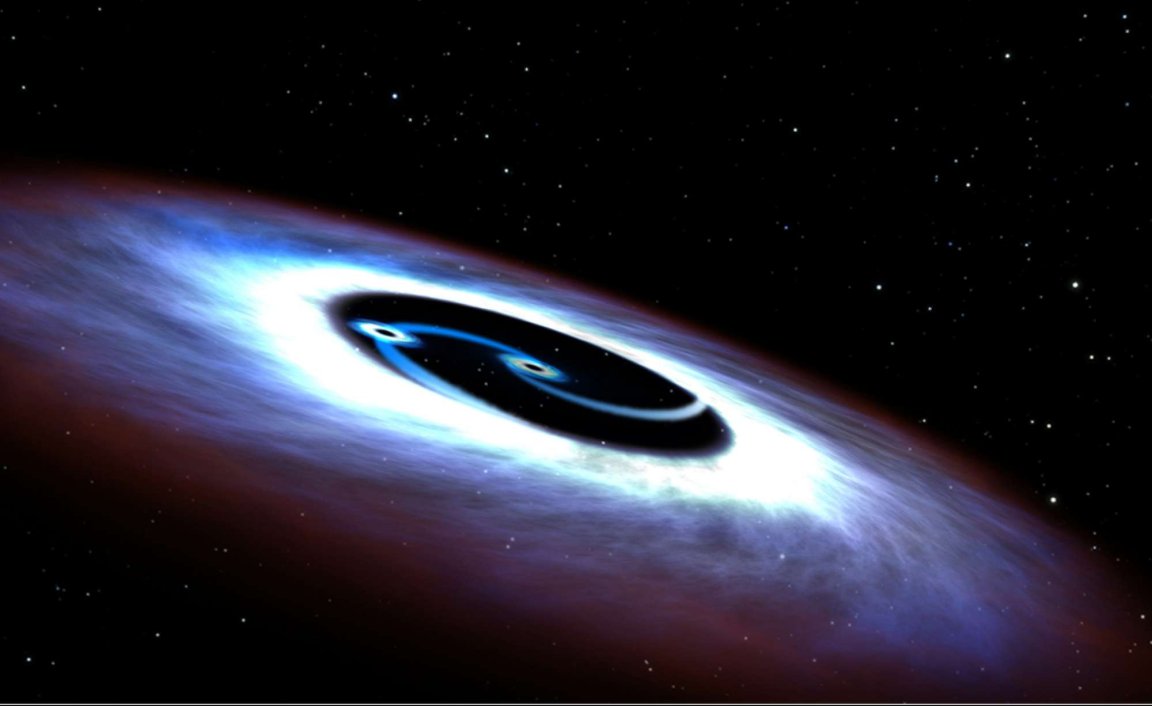

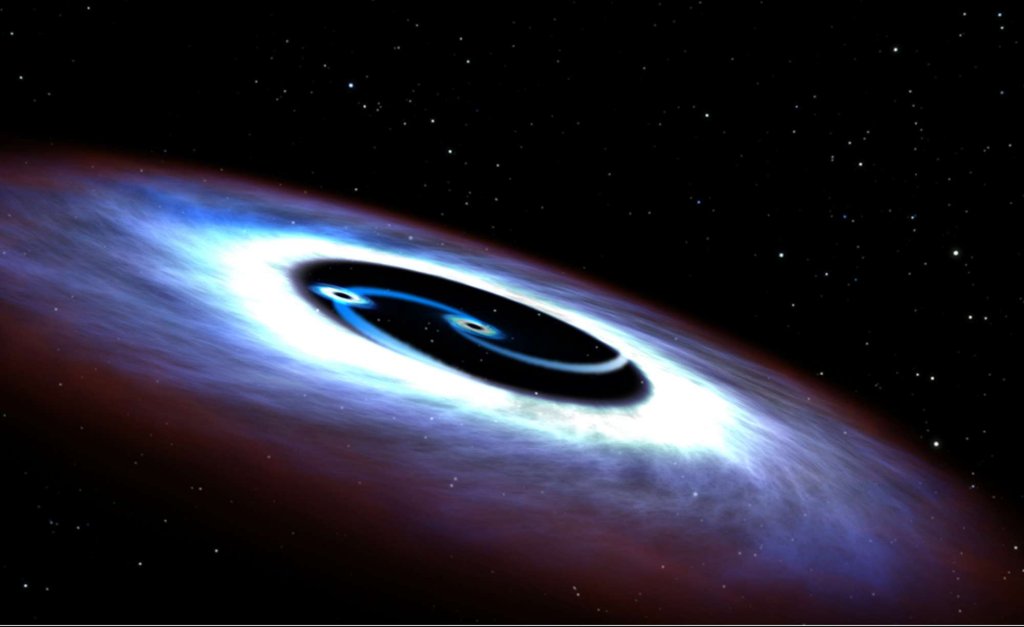

In order to uncover this find, scientists looked at Hubble archival observations of ultraviolet radiation emitted from the center of Mrk 231. If only one black hole were present in the center of the quasar, the whole accretion disk (the whirlpool of superheated gas that surrounds the black hole) would glow in ultraviolet rays. However, when scientists look at this area, they see that the ultraviolet glow abruptly ends near the central region. As such, we have observational evidence that there is a large hole surrounding the black hole.

The best explanation for this observation is that there are two black holes orbiting each other. To break this down a bit, scientists assert that the most likely solution is that there is a small black hole in orbit on the inner edge of the larger black hole’s accretion disk.

Of course, “small” is a relative term. The black hole that is in orbit is estimated to be 4 million solar masses and seems to have an orbital period of about 1.2 Earth-years. The central black hole is a rather hefty 150 million solar masses.

The binary black holes are predicted to spiral together and collide within a few hundred thousand years, which will, with any luck, provide an amazing show for any life that is still hanging about on our little planet.