“Life is not a miracle. It is a natural phenomenon, and can be expected to appear whenever there is a planet whose conditions duplicate those of the Earth.”

Such were the words of Harold Urey, physical chemist famed for his contributions to our understanding of organic matter. Indeed, ever since humanity’s search for extraterrestrial organisms began, we have found thousands of planets which may have the right criteria to support life, and astronomers predict that there are several billion planets situated in their circumstellar habitable zone – also known as the ‘Goldilocks Zone’.

Although many have heard of the Drake Equation, a formula estimating the number of intelligent civilisations currently alive in the universe, the more relevant measure in our endeavour to find alien life is the Earth Similarity Index (ESI). This scale, which takes into account several factors including radius, density, escape velocity, and surface temperature, seeks to quantify how similar any given planet or moon’s physical characteristics are to our Earth. Whilst some exoplanets have ranked remarkably high, such as Kepler-438b with an ESI of 0.89 out of 1.00, and Gliese 667 Cc with an ESI of 0.84, most of these are several hundred light years away – well out of our reach for modern technological standards.

What about inside our very own solar system? Well, there are three candidates which have been regarded as serious prospects for extraterrestrial life in recent years: Jupiter’s moons Europa and Ganymede, and Saturn’s moon Enceladus. In fact, just last month, NASA announced the exciting news that it had requested $255 million in funding for an exploration mission to Europa. However, according to the ESI, none of these moons rank any higher than 0.3 on the scale; so why are they deemed to hold such potential for life? The answer lies in oceans, geysers, and hydrothermal vents.

Europa

Out of all the factors it takes for a planet to support life, the presence of liquid water has always been considered one of the most vital. Many will remember the discovery of water on Mars, which suggested much about the red planet’s distant past. Although many alternative theories propose that other biochemical environments, such as the methane lakes found on Saturn’s moon Titan, could also hold the necessary hydrocarbons to harbour living organisms, our only real precedent for life is what we observe right here on Earth.

According to latest research, under its thick icy crust, Europa is likely to have a vast sub-surface ocean which is kept in liquid form due to tidal heating from Jupiter. Based on information from NASA’s Galileo satellite, it contains up to 3 times as much water as found on Earth, even despite Europa’s smaller overall size.

“Europa’s ocean, to the best of our knowledge, isn’t that harsh of an environment” says astrobiologist Kevin Hand. Indeed, although its ocean could be as deep as 100km, living organisms have been found in places with equally difficult conditions on Earth, such as the famous Mariana Trench. Unlike the outdated view that photosynthesis from sunlight is an absolutely essential component of life, scientists in the last couple decades have concluded that microbial life can survive via chemosynthesis by processing chemicals from hydrothermal vents.

“Europa is a very challenging mission operating in a really high radiation environment, and there’s lots to do to prepare for it” said Beth Robinson, NASA’s chief financial officer. The exploration mission, named Europa Clipper, is set to be launched in the mid 2020s. It will seek to observe the moon’s topography, examine the thickness of its ice crust, and analyse the sub-surface ocean’s ability to sustain life. If NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) is finished on time, it will allow Europa Clipper to be sent from Earth to Jupiter in only 3 years rather than the conventional travel time of 8 years.

Perhaps the most unconventional opportunity to obtain a sample from Europa’s ocean will come from its water-rich geysers which can reach 200km in height – twice as high as Earth’s atmosphere. If NASA is able to plan Europa Clipper’s orbital trajectory in a way that allows it to pass by the moon’s southern pole, it could fly directly through a jet of water vapour, collecting water particles and thus avoiding the difficult task of having to land on Europa’s surface altogether.

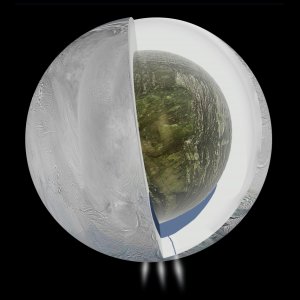

Enceladus

Saturn’s sixth-largest moon was recently found to be one of the most promising places for life in our solar system outside of Earth, perhaps even surpassing Europa in its prospects for habitability.

In 2005, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft found plumes of water vapour emanating from Enceladus’s southern pole, reaching heights of 200km, just like those observed on Europa. In 2014, it discovered the existence of a warm sub-surface ocean with an estimated depth of only 10km. Now, in 2015, astrophysicists working on the Cassini mission have just announced that they detected ongoing hydrothermal activity in Enceladus’s ocean – the first of its kind ever to be found besides Earth.

Surprisingly, the scientists behind this discovery explained that they collected this data not by examining Enceladus itself, but by observing the dust found in Saturn’s majestic rings. “We’ve known from quite early on that Enceladus was the source of the material in Saturn’s outermost ring […] based on the ring’s composition” said Sean Hsu, researcher at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Using Cassini’s mass spectrometer, they were able to identify a type of silicon particle which, as far as we know, can only be formed by hydrothermal vents.

According to Andrew Coates, Head of Planetary Science at UCL, the vital chemistry for life involves carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulphur. Evidence suggests that Enceladus’s ocean contains many of these, with nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane having already been identified. This leaves little doubt that the moon could harbour microbial organisms, and maybe even small aquatic animals.

However, unlike Earth’s hydrothermal vents which are fuelled by the planet’s hot core, Enceladus’s warmth is a result of tidal heating from Saturn, just like that which is observed on Europa. What this means is that Enceladus may not have had the same timeframe of hydrothermal activity as seen on Earth. As we know, life takes millions of years to form, and so it is unclear whether Saturn’s moon would have had enough time to develop and sustain its own organisms. Nonetheless, with an ocean holding about as much water as Lake Superior, Enceladus’s small size makes it a truly exciting place to explore.

Jonathan Lunine, planetary scientist from Cornell University, is currently drafting a proposal to update the Cassini mission by sending a new spacecraft to Saturn with better technology and tools designed specifically to find any signs of life. “If we go back to Enceladus and build upon the Cassini results with the instruments of today, the short answer is, we know that we’ll be able to look for life frozen in the geyser particles, and really nail this habitability question”.

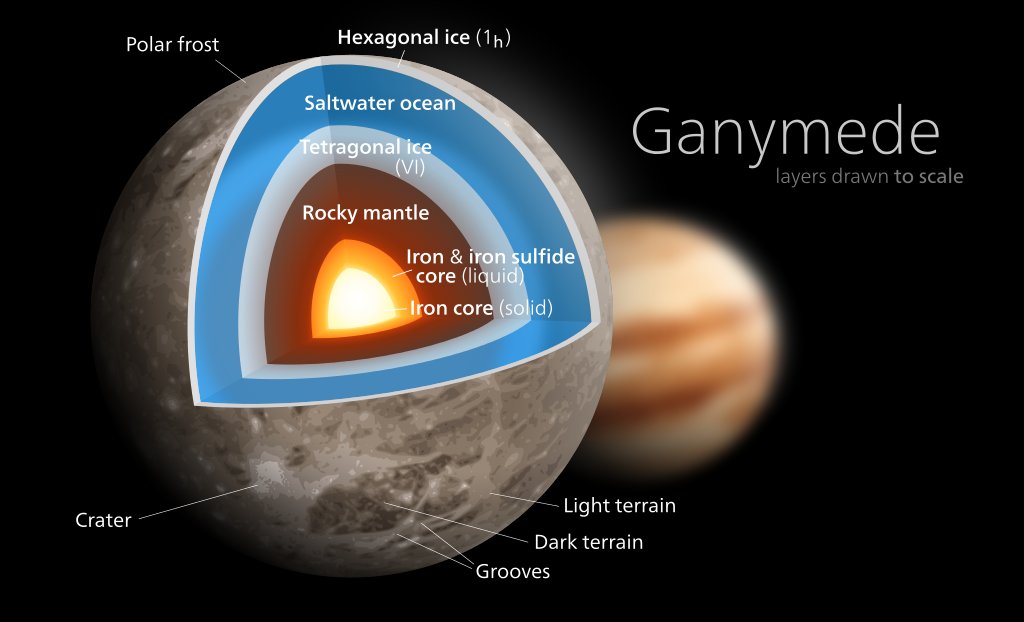

Ganymede

“The solar system is now looking like a pretty soggy place” says Jim Green of NASA. In breaking news last week, Jupiter’s largest moon Ganymede was also found to have a sub-surface ocean, putting it up on the same ranks as Europa and Enceladus.

These findings came about from observations of the moon’s aurora, which are the equivalent of the Northern Lights phenomenon seen here on Earth. Having noticed an unusually low shift in the aurora’s magnetic interactions with Jupiter, Joachim Saur, along with his colleagues from the University of Cologne, found that this was the result of Ganymede’s saltwater ocean which was acting as a separate magnetic source. Just like Europa, Ganymede’s ocean is also predicted to be around 100km in depth. Evidence suggesting the existence of a sub-surface ocean had been spotted in 2002 by NASA’s Galileo probe, but the data was not yet conclusive at the time.

Despite being a moon, Ganymede is around 5,268 kilometers across, making it only 30% smaller than Mars. In fact, if it had formed around the sun instead of Jupiter, it would be massive enough to be classified as a planet. Whether or not life exists on Ganymede will have to be examined in the next decade, but, just like Europa and Enceladus, its potential for habitability is substantial. “Every observation we make takes us one step closer to finding a truly habitable environment” says Heidi Hammel, planetary scientist at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

The European Space Agency (ESA) plans to send a specialised probe to examine Jupiter’s moons in 2022, the Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer – also known as JUICE. It aims to collect data from Ganymede, Europa, and Callisto, with emphasis on determining whether or not extraterrestrial organisms could thrive in their respective environments. The mission would take over 8 years and enter Ganymede’s orbit around 2033.

The meaning of life

Whilst many of these exploration projects may seem to be decades away from finding alien life, their importance cannot be overstated. Discovering living organisms outside of Earth would be the single most revolutionary event in the history of mankind.

From a scientific viewpoint, it would allow us to observe life which is completely unfamiliar to us here on Earth, giving immense insight into the possibility of survival in alternative biochemistries. So far, astrobiologists have conventionally assumed that Earth-like conditions, as reflected by the ESI, are the most likely to harbour life. This view could soon be completely overhauled and replaced by a more flexible outlook in our future search for extraterrestrials.

More importantly, the philosophical significance of such a discovery would be immeasurable. Many of our religions, politics, and theories about the meaning of life are based on the assumption that we are alone in this vast universe. Detecting alien organisms within our very own solar system would dramatically change the underpinning structure of our philosophy and directly challenge the teachings of major faiths around the world. As an Epicurean like myself would say, it would prove that we humans are neither special, nor divinely entitled to the nature of our planet that we so often take for granted.

All we can do for now is be patient and wait for the day that every newspaper will print the historic headline “Scientists find alien life”. With many exploration missions in their planning phase this decade, several of which are ready to launch in the 2020s, that day may just come sooner than we all expect.

Provided by Bartu Kaleagasi at The Social Humanist.