Black holes are some of the most powerful and perplexing objects in the known universe. They are infinitely dense objects that warp spacetime so much, nothing (not even light itself) can escape their grasp. But of course, black holes aren’t the only strange objects that we know of. If there’s anything that can rival the power and quantum craziness of black holes, it’s pulsars.

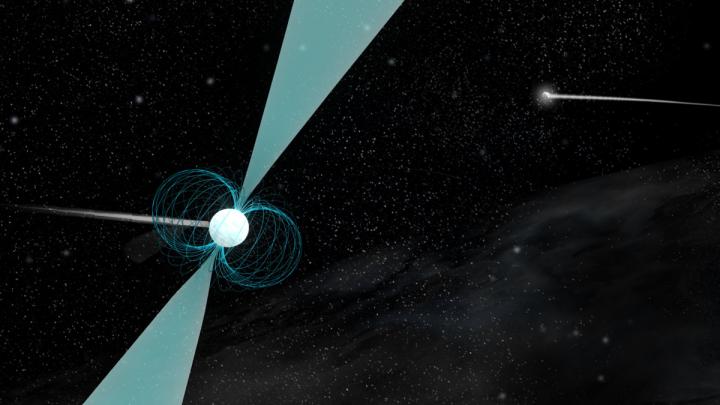

Pulsars are a kind of star. Specifically, they are neutron stars that are rotating at amazing speeds and pointing right at us. Many spin up to 700 times per second (though other, more extreme pulsars have been found to go even faster). And though they are only 6 miles in diameter (10 km), they are generally about 1.5 times more massive than our own sun.

One of the strangest pulsars that we’ve ever discovered is one that shares its space with a fellow star.

The pulsar, which has since been dubbed PSR J1930-1852, was discovered back in 2012 by a team of high-school amateur astronomers from Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Baltimore, Maryland. According to NRAO, “These students were participating in a summer Pulsar Search Collaboratory (PSC) workshop, which is an NSF-funded educational outreach program that involves interested high school students in analyzing pulsar survey data collected by the GBT.”

After the object of interest was noted, the group joined a team of researchers from Green Bank Observatory to confirm the discovery, and to determine what characteristics it may have.

This closer look revealed that its spin frequency changed between the original viewing and those that were carried out at Green Bank. Ultimately, this suggests a companion is part of the equation. The researchers were able to immediately rule out a main-sequence star, as they are much larger and more prominent than stellar corpses (like white dwarfs), so if it did have a companion that was a main sequence star, we be able to clearly see it.

Joe Swiggum, a student from West Virginia University, noted in the press release, “Given the lack of any visible signals, and the careful review of the timing of the pulsar, we concluded that the most likely companion was another neutron star.”

To delve into this a bit more, pulsars are siblings to neutron stars…they form in the exact same manner—when a massive star reaches the end of its life, its core collapses in on itself and triggers a supernova event (one of the most powerful events in the universe). The only real difference between a pulsar and neutron star is how we perceive them from Earth.

The magnetic axes of pulsars are aimed right at us, allowing us to see their pulsating radio emission (they also emit other forms of radiation). However, neutron stars, unlike pulsars, are positioned in such a manner that we are unable to see any activity happening at their poles.

When two highly dense objects are in close proximity, some seriously strange things follow. In their press release, NROA explains:

Some pulsars in double neutron star systems are so close to their companion that their orbital paths are comparable to the size of our Sun and they make a full orbit in less than a day. The orbital path of J1930-1852 spans about 52 million kilometers, roughly the distance between Mercury and the Sun and it orbits its companion once every 45 days.

“Its orbit is more than twice as large as that of any previously known double neutron star system,” said Swiggum. “The pulsar’s parameters give us valuable clues about how a system like this could have formed. Discoveries of outlier systems like J1930-1852 give us a clearer picture of the full range of possibilities in binary evolution.”

Studies involving Pulsar Search Collaboratory discoveries are ongoing; as the PSC program continues, astronomers expect the 130 terabytes of data produced by the 17-million-pound GBT will likely reveal dozens of previously unknown pulsars.

[Reference: Eurekalert!]

Astronomers have cataloged well over 2,000 pulsars over the years. Usually, these stars are isolated and alone, just 10 percent lurk within binary systems, and the companion is usually a less massive white dwarf. Very rarely do we ever happen across a pulsar that has another pulsar, a neutron star, or a Sun-like star as a companion.

“When a massive star goes supernova at the end of its normal life, the explosion can be a little one-sided, imparting a “kick” to the remaining stellar core. When this happens, the resulting neutron star is sent hurtling through space. These kicks—and the corresponding mass loss from a supernova explosion—mean that the chances of two such stars remaining gravitationally locked in the same system are remarkably slim.”

From Quarks to Quasars is two people, Jaime and Jolene. We want to make the world a more sciencey place. We’re doing that, but with your help, we can do even more.

FQTQ takes a lot of time, money, and effort. Here, you can support us, get to know us, and access extra content: