A Tale of Two Diseases

One of the greatest tragedies of our modern times is a disease that we are helpless against. It goes without saying that a single diagnosis is a harbinger of despondency to a litany of loved ones. But from these diagnoses, though bittersweet, there may be clues to the most bewildering of all conditions: neurodegenerative diseases.

A neurodegenerative condition that most of us are aware of is Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s presents itself in three stages, preclinical, mild cognitive impairment(MCI), and finally dementia. While the first stage is symptomless and the second presents mild symptoms, the final stage is what most of us imagine when we think of the disease—an utter loss of memory and mental faculty.

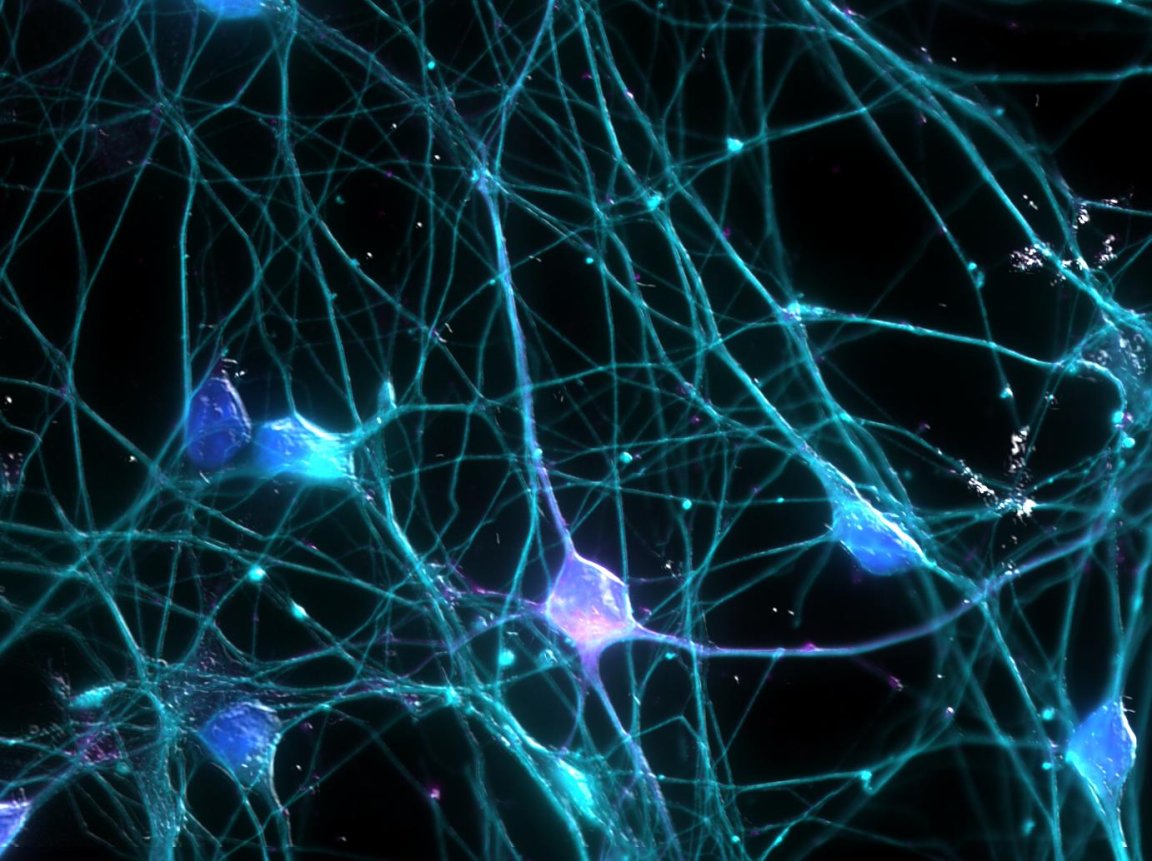

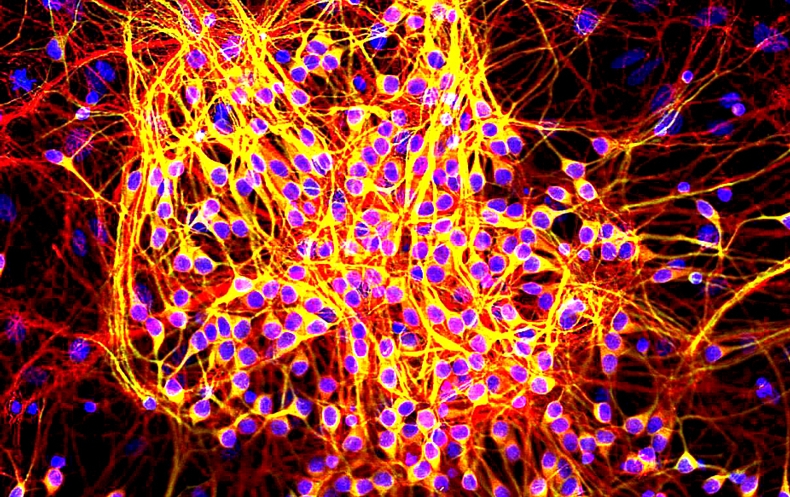

A believed progenitor of the condition is a mutation that deposits clusters of the amyloid-β-protein in regions of the brain involving memory over time—eventually affecting day-to-day processes such as speech, coordination, and recall. There currently is no cure or treatment for the disease, even though we have seen progress.

Yet, a lesser known disease may get us on the path to something viable. Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a disease that is undocumented two times out of three in the fewer than twenty thousand people in the US that have it. While both PSP and Alzheimer’s affect similar faculties in patients, PSP differs noticeably.

And it could be the key to Alzheimer’s.

What’s the hubbub with PSP?

PSP is a condition that is derived primarily from the build-up of Tau proteins —unlike Alzheimer’s, which is derived from the involvement of both amyloid-β-protein and Tau protein. Even though we can’t identify the genetic component of the tau protein in Alzheimer’s patients, we can find the genetic component in PSP patients, with a 5.5 fold increase in susceptibility to PSP if a mutated tau sequence is found.

So what does all of this really even mean?

With a strong genetic component, smaller population size, and an uncanny similarity to Alzheimer’s: PSP might give us a good shot at understanding the monster that is Alzheimer’s in an unconventional way. While PSP patients are difficult to find, the disease is easier to predict and therefore makes running clinical trials faster and less expensive.

Trials that take thousands of people and over a year in Alzheimer’s patients only requires a few hundred people with PSP and takes less than a year.

At the end of the day, every diagnosis, case, and story may just help us build a better future for the families of tomorrow.