Ever since the first “test-tube baby” was born in 1978, hopeful parents-to-be have turned to in vitro fertilization (IVF) to help them get past difficulties conceiving. Almost four decades later and an estimated 5 million babies have been born through assisted reproduction technology.

While the thought of all those happy families is heartwarming, IVF is a controversial practice complicated by legal, moral, and technological limitations. Now, one of those technological limitations is being challenged, and it’s forcing both legislators and society at large to rethink their own boundaries.

The Birds and the Bees and the Lab

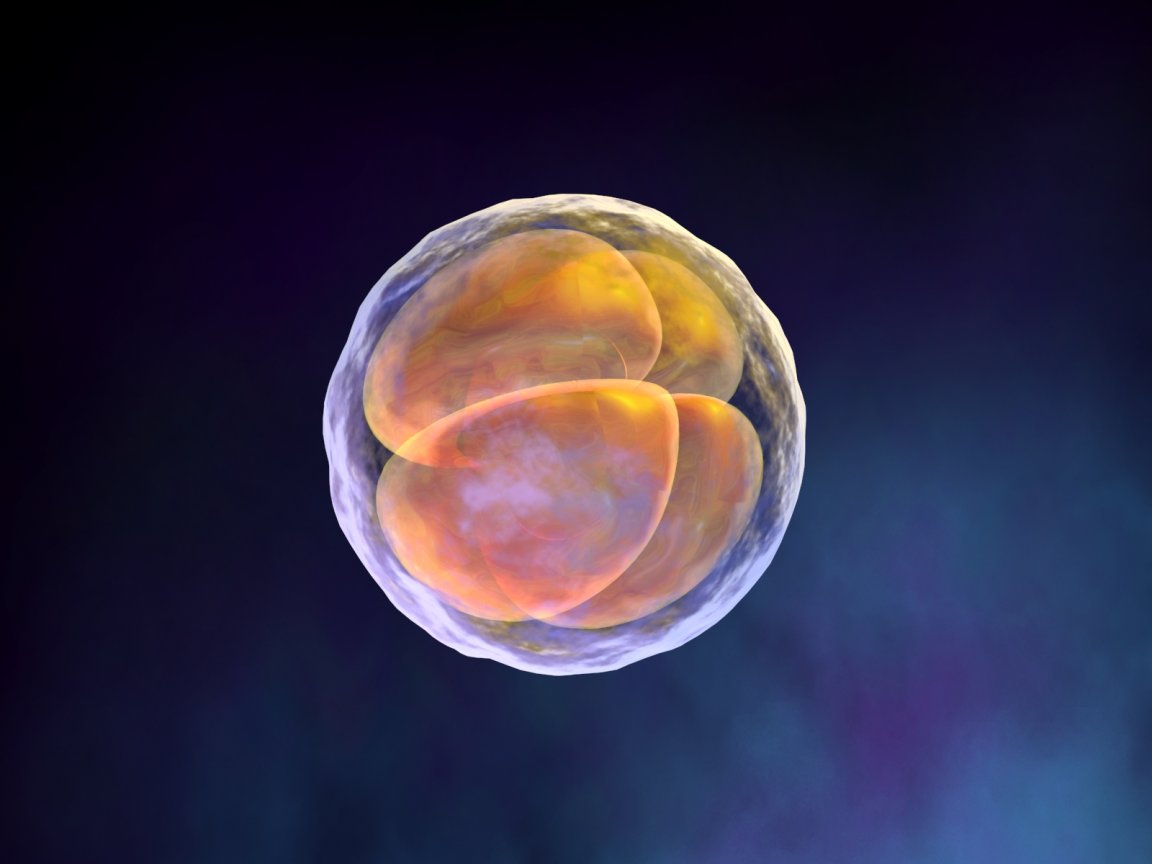

At the center of this debate are embryos. During the process of IVF, sperm and eggs are brought together in a laboratory dish so that the sperm can fertilize the egg to create an embryo. Those embryos are then incubated in that dish for 48 to 120 hours, at which point the doctor chooses the fertilized eggs most likely to result in a pregnancy. Those eggs are implanted in the patient’s uterus and, if all goes well, nine months or so later a baby is born.

To improve the chances of getting a viable embryo, doctors typically start the process by fertilizing more eggs than they plan to implant. After IVF, those extra eggs can be frozen for future use by the same patient or donated to another patient who may not have viable embryos of their own. The embryos can also be donated for research purposes. That’s where the controversy heats up.

14 Days to a Better Embryo

At this stage, the embryo is a cluster of cells roughly 0.1 – 0.2 millimeters in diameter, and they have been bestowed certain rights due to the controversy surrounding the point at which human life actually begins. Unlike medical trials involving adult humans, embryos cannot consent to research experiments, so others have stepped up to ensure that the line between humane scientific research and human experimentation isn’t crossed.

In 1982, four years after the birth of that first test-tube baby, the British government assembled a committee to investigate embryonic research related to IVF, and determine how to best regulate it. That committee concluded that researchers should be allowed to conduct research on embryos up until they are 14 days old. The reasoning? At that stage of development, an embryo would definitely not have a spinal cord or central nervous system. Without a nervous system, there’s no way the embryo can feel pain.

The 14-day limit on embryonic research was soon adapted by other countries and has remained in place as the standard for the last several decades, during which embryonic research has allowed scientists to learn much about human development. It’s also greatly improved IVF technology. Early success rates for the procedure were about 12 percent, but according to the American Pregnancy Association, roughly 42 percent of women younger than 35 who begin IVF treatment now give birth to a live baby as a result of the treatment. Even among the higher-risk demographic of women over the age of 40, the success rate is 15.5 percent.

New Development, New Controversy

Embryonic research would still be business as usual if not for one new development. While the 14-day time limit imposed on embryonic research did have a moral reasoning behind it — no spinal cord, no pain — it had a bit of a practical one as well: at the time of the rule’s establishment, no one could keep an embryo alive for even close to 14 days anyway. In fact, most researchers hit a wall at around day five.

In March, researchers at Cambridge University published a study in Nature showing that they could keep an embryo alive in a lab setting for 13 days. Not only that, the embryo didn’t die at 13 days. “When we reached the 13th day, we stopped the experiment because we were so near the legal limit,” lead researcher Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz told The Guardian. “We could have gone to the limit, but I don’t know how much longer the embryo would have survived.”

Which Path To Take?

And now, just like in 1982, legislators, researchers, and the rest of the world’s citizens find themselves at a fork in the road with respect to embryonic research: keep the 14-day limit in place and take one path, or extend it in light of this new development and take another.

Either path will no doubt lead to remarkable innovations. Prior to this breakthrough, researchers were unable to learn much about how embryos develop outside the womb between days seven and 14. This extra week could be enough time for biological information to surface that would help doctors choose the very best embryos for implantation, potentially improving IVF rates even more drastically without having to revisit the legal and moral implications of embryonic research.

The other path, however, the one in which we extend the time limit on research, brings all those messy questions back to the forefront. Do we know for sure that a spinal cord would mean the embryo could actually feel anything? Do we even know that an embryo has a spinal cord at, say, day 21? What about day 28? That latter milestone has been proposed as a potential replacement for the current two-week limit as it contains the human embryo’s gastrulation period, the time during which the embryo’s cells reorganize from being a cluster of cells into a multi-layered organism.

The amount of information we could learn about human development from studying that period would be enormously significant. “Certain tumors, developmental abnormalities, miscarriage: there is a whole raft of issues in medical science that we could start to understand if we could carry out research on embryos that are up to 28 days old,” IVF expert Professor Simon Fishel, told The Observer. But does it cross the moral line into human experimentation?

Made-To-Order Embryos

Complicating matters is the fact that researchers don’t need to rely on unused IVF embryos for research anymore, nor are they limited to traditional embryos. They can now create embryos that don’t include a donor egg, are half human and half animal, are clones of other embryos, and ones that contain DNA from three parents. If they’ve been able to do all that with the current limit in place, what will they be able to do if it is extended?

For now, the 14-day limit is in place and will remain so for the time being. However, the same way the U.K. helped the world reconcile its ethical and practical concerns so that we could more forward with embryonic research back in the 1980s, it’s only a matter of time before someone steps up to help us choose which path to take now that the landscape has changed once again.