Studying Heart Failure

A team of researches from the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas have discovered a way to reverse severe heart failure, one of the leading causes of death from heart disease. The discovery, which involves “silencing” the Hippo pathway in the heart, could lead to better treatments for those at risk of heart failure — potentially ones that could eliminate the condition entirely.

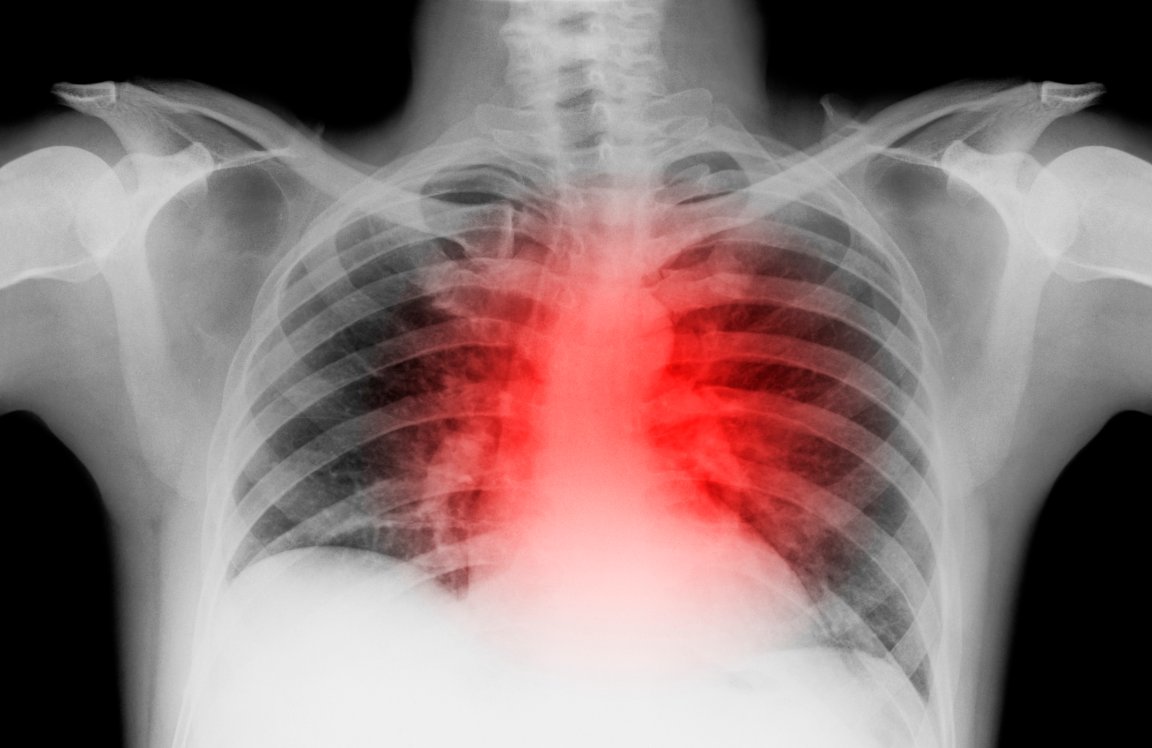

Contrary to its name, heart failure (also known as congestive heart failure) is not a condition in which the heart suddenly stops beating. Instead, it’s a condition in which the heart is unable to pump enough blood and oxygen to the rest of the body. It’s most likely to occur in those who have experienced a heart attack, during which blood and oxygen cease to flow to the heart. This lack of oxygen causes part of the heart muscle to die and be replaced by dead scar tissue, known as fibroblasts. Over time, the heart weakens to the point of being completely unable to support the body.

To study the condition, the team from Baylor College started by creating a mouse model that could be substituted for a human heart suffering from heart failure. Animals models are often used to study the same/similar diseases and conditions that can affect people. In the case of heart failure, the hearts of mice and humans are incredibly alike, making the former perfect for studying the heart and testing potential treatments.

“One of the interests of my lab is to develop ways to heal heart muscle by studying pathways involved in heart development and regeneration,” explained Dr. James Martin, Vivian L. Smith Chair in Regenerative Medicine at Baylor and corresponding author of the research. “In this study, we investigated the Hippo pathway, which is known from my lab’s previous studies to prevent adult heart muscle cell proliferation and regeneration.”

Improving the Heart

The decision to hamper the Hippo pathway came as a result of the increased activity that occurs within it during heart failure. According to John Leach, primary author and graduate student of molecular physiology and biophysics at Baylor College, the team believed if they could turn it off, the heart may improve. Turns out they were right.

“Once we reproduced a severe stage of injury in the mouse heart, we inhibited the Hippo pathway,” said Leach. “After six weeks we observed that the injured hearts had recovered their pumping function to the level of the control, healthy hearts.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that over 5.7 million people in the U.S. live with heart failure, with about 50 percent of people diagnosed expected to die within five years. While Dr. Martin and Leach’s research yields favorable results, there is more work that needs to be done with regards to hindering the Hippo pathway.

Specifically, turning off the Hippo pathway has two effects: one is increased muscle cells capable of surviving inside the damaged heart, while the second is the altered fibrosis. Fibrosis plays a key role in the dead scar tissue that forms during a heart attack. Before any test can be done on people, the team will need to ascertain a better understanding of the changes in fibrosis. Hopefully that leads to a positive discovery that can save more people sooner, rather than later.