Giving Sight to the Blind

Visual impairment is still rather rampant, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Some 285 million people worldwide are considered visually impaired, and 39 million of them are blind. Thankfully, 80 percent of all visual impairment can now be treated or cured, except in cases of total loss of sight, particularly those due to severe retinal degeneration.

But what if it’s possible to restore visual function to blind patients? Laboratory tests in the University of Oxford demonstrate how this may be possible. In a study published in the journal of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the Oxford researchers led by Samantha de Silva showed how it’s possible to restore the sight of people suffering from blindness previously considered untreatable.

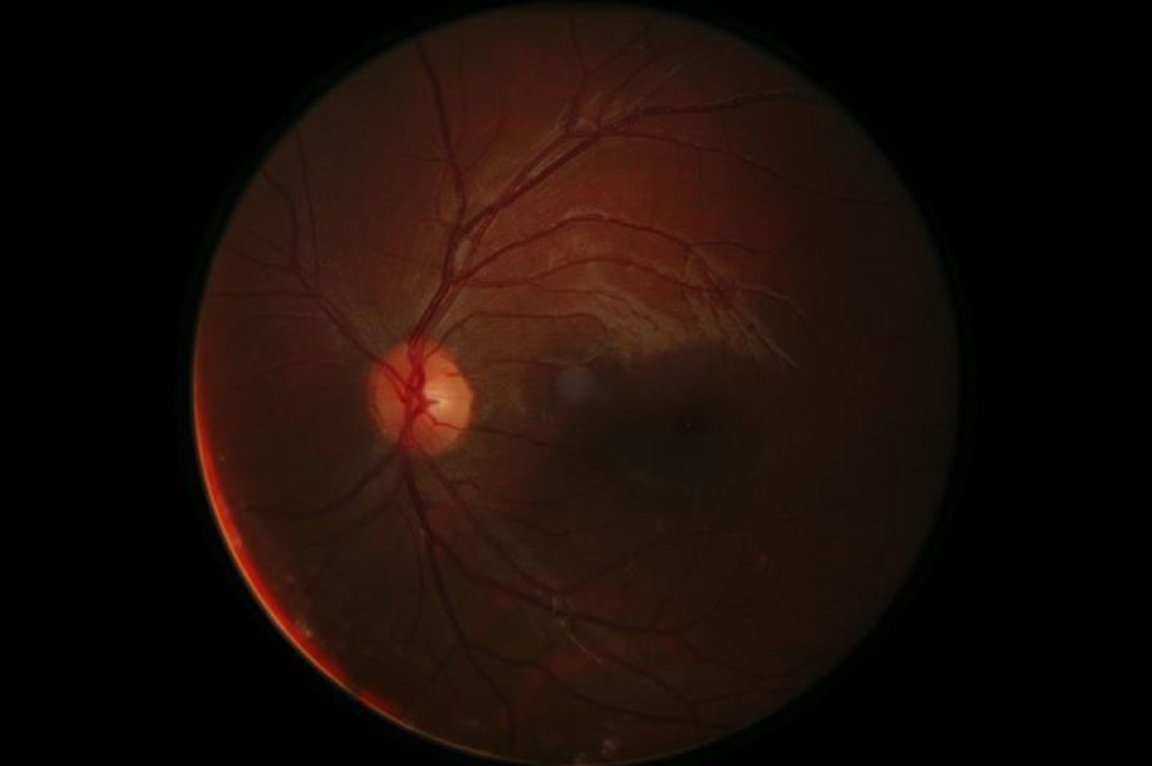

“Inherited retinal degenerations may result in blindness due to a progressive loss of photoreceptor cells,” the researchers wrote. “We assess subretinal delivery of human melanopsin using an adeno-associated viral vector to remaining retinal cells in a model of end-stage retinal degeneration.”

Light Sensitivity

Using gene therapy, the researchers introduced a viral vector in retinal cells found at the back of the eyes that weren’t originally sensitive to light. The viral vector introduces a light-sensitive protein called melanopsin, which enables these residual retinal cells to respond to light and send visual signals to the brain. In lab tests with mice suffering from retinitis pigmentosa, the most common cause of blindness in young people, the researchers were able to maintain sight in the mice for over a year. The mice demonstrated high levels of visual perception, recognizing objects in their environment.

It’s worth noting that de Silva and her colleagues have also been successfully trialing an electronic retina. However, they observed that gene therapy may be simpler and easier to administer. Similar work has been done by others involving age-related blindness, while an FDA-approved gene therapy seeks to cure hereditary retinal blindness.

The results are quite promising, and de Silva noted how much hope this treatment gives to patients suffering from blindness. “There are many blind patients in our clinics and the ability to give them some sight back with a relatively simple genetic procedure is very exciting,” she said in a press release. “Our next step will be to start a clinical trial to assess this in patients.”