Fighting Fear

Fear is something basic and primal in all of us. And it can have a very real impact on our lives—just ask people with severe phobias or PTSD. That’s why we go to great lengths, therapy, medication, or even using AI, in order to purge the source of the fear from our bodies.

Now, a new study may help in eliminating certain fears. Chinese scientists have been able to reduce fear response times by combining traditional fear extinction training and transplantation of embryonic interneurons into the brain.

In their study, the researchers first conditioned fear into mice by exposing them to sound and then shock. This creates fear when the sound is heard, exhibited by freezing behavior. Researchers then conducted fear extinction training, basically playing the sound without delivering the shock. The freezing response times were reduced.

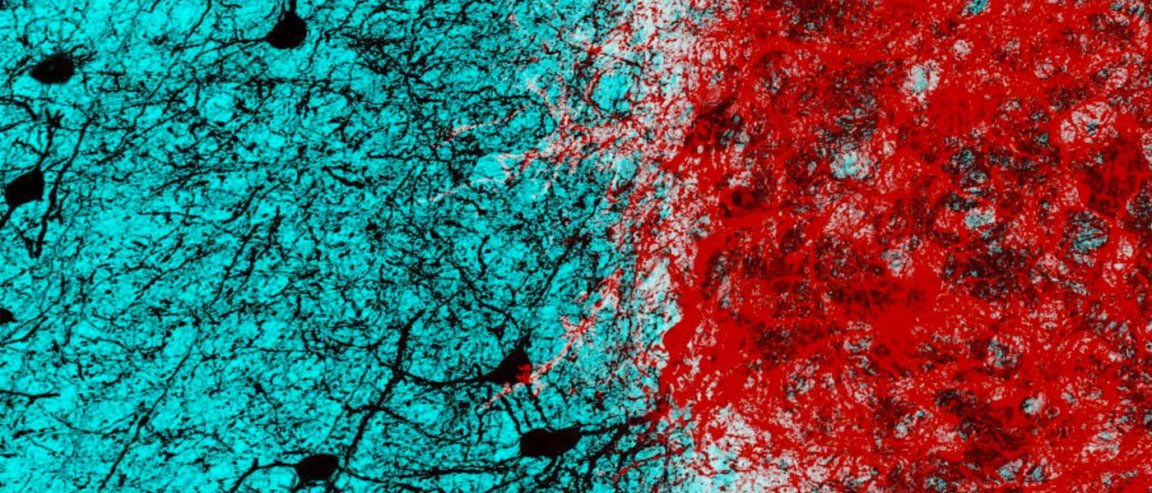

The researchers then inserted immature interneurons into the structure of the brain responsible for fear and emotion— the amygdala. They found that the interneurons can help with the extinction training. But instead of preventing the formation of new fear memories, they help reduce that training time. The embryonic interneurons induce plasticity into the mature amygdala, allowing it to “reset” to a more juvenile state.

The Unknown

This new study presents exciting possibilities in understanding how fear works. But we still have a long way to go in studying this particular method. “We still don’t know the mechanism by which these immature neurons modulate the fear extinction behavior in the mice,” says senior author Yong-Chun Yu in a statement.

That means any human trials for similar treatment are a long way off. If it does prove safe and effective, this research could help in treatments and therapies for anxiety and fear-related disorders, like PTSD. There are current treatments and methods, but they do have their shortcomings.

“Pharmacological and behavioral treatments of PTSD can reduce symptoms, but many people tend to relapse. There’s a pressing need for new strategies to treat these refractory cases,” says Yu.