Imagine this: you’re a physician at one of the most renowned medical institutions in the world. A patient comes in with a very aggressive form of cervical cancer and you collect her cells to study them for her particular case. But while studying her cells, you notice something odd. After a certain number of cell divisions, they don’t die like other cells in the research lab. In fact, they don’t die at all.

It’s the year 1950 and it’s years before any regulations on harvesting cells from patients are mandated. In fact, there is no custom of asking permission for cell collection for research. With that said, you think about all the potential these “immortal cells” may have. You have never seen cells quite like them before in your life, and you know for a fact that your colleagues and other researchers around the world have not either.

What do you do?

To George Otto Gey, it was simple: collect the cells and propagate them for future research. His patient was a 31-year-old woman named Henrietta Lacks.

The birth of a medical revolution

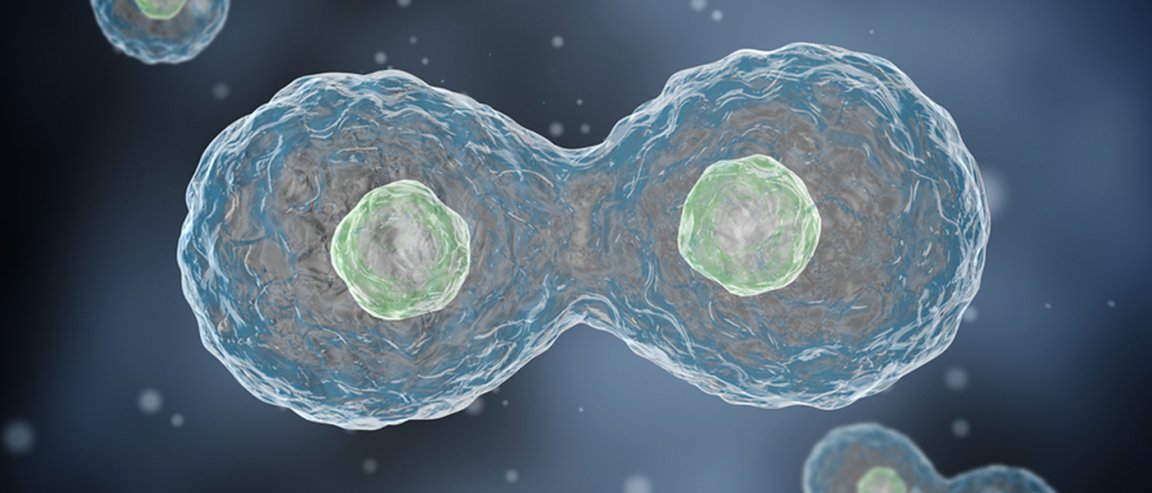

Henrietta Lacks’s cancer cells were quickly dubbed “HeLa cells” in the scientific community. Even 60 years after their collection, HeLa cells are still the most commonly-used cell line around the world, having been produced billions and billions of times now. This is because HeLa cells were the first cells to survive in vitro (in a test tube) and provided the foundation for some of the most remarkable discoveries in modern medicine.

If you have ever had the polio vaccine, you can thank Henrietta Lacks for her cells. From 1840 to 1950, Poliomyelitis was a lethal global epidemic that not even President Franklin D. Roosevelt was spared from. He declared a war on the disease. The vaccine developed by Jonas Salk in 1952 was only possible because HeLa cells were able to survive in vitro. The HeLa cells were easy to infect and study, and therefore provided the perfect subject for Dr. Salk to utilize in his research. With only 403 cases in 2014, polio has been on the run. The vaccine has prevented 650,000 deaths and 13 million cases of paralysis since 1988. All of this would not have been possible if it weren’t for Henrietta Lacks’s immortal cell line.

Henrietta Lacks’s cells were the foundation of opening the field of virology in the first place. But that’s not all: her contribution to modern medicine moves past just vaccines. Her cells have allowed us to study cancer, cell growth in space, HIV, the human genome, Tuberculosis, HPV, Parkinson’s disease, and even cosmetics.

Henrietta Lacks’s contribution to modern medicine is clear—without her cells, who knows where we would be today? While medical progress is often thought of as inevitable, it’s by chance events like the discovery of Lacks’s cells that the rate of progress is decided. Her cells were the catalyst to many medical advances that we have today.

For more information: