First Response

In 2010, researchers discovered that humans are born with innate lymphoid cells (ILCs). They’re a crucial part of the body’s ability to fight off infections and are highly concentrated in parts of the body that are more likely to come under the threat of infection, such as the gut, lungs, or skin.

Now, a new study published in Nature has offered up additional insight into how they work in tandem with our nervous system.

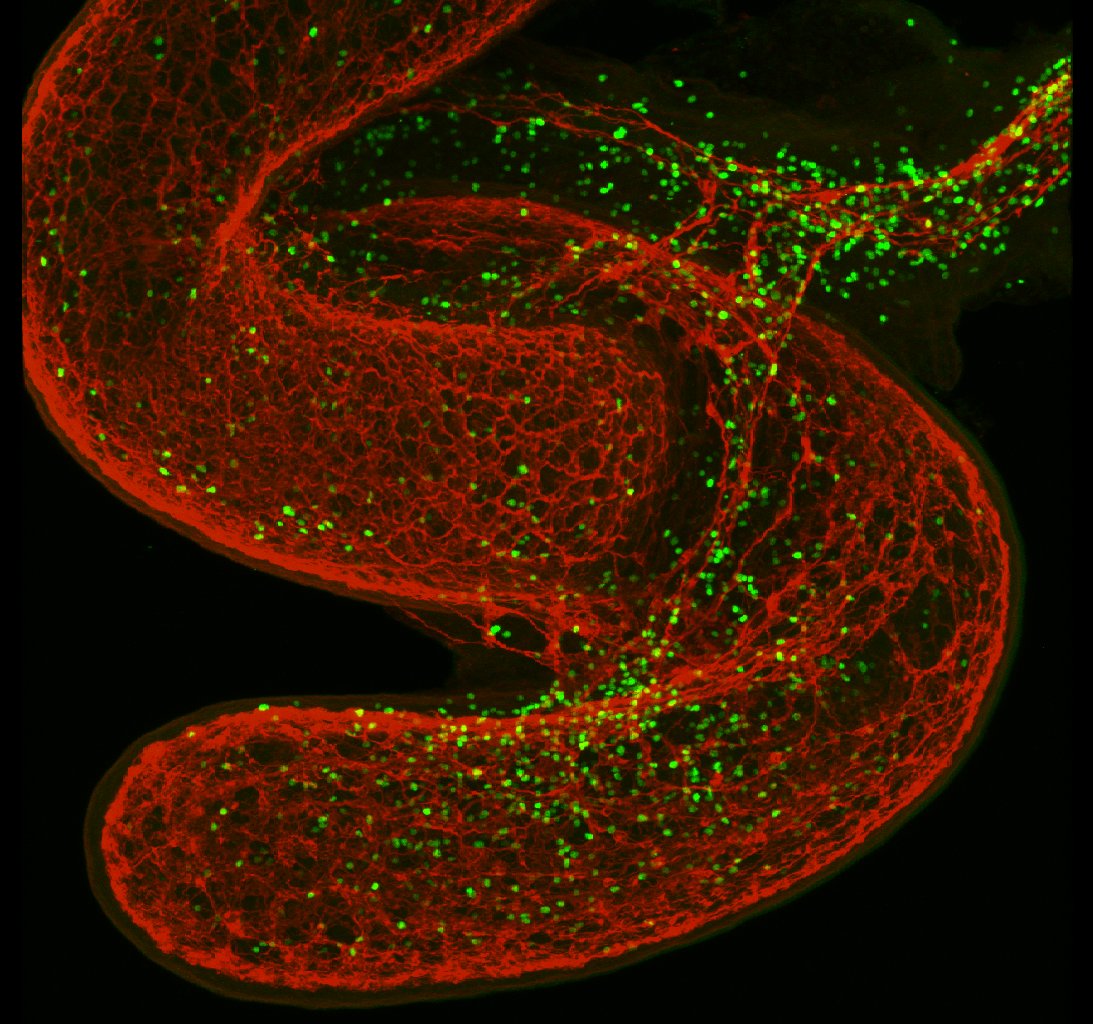

Researchers from the Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown (CCU) and the Instituto de Medicina Molecular (IMM) in Lisbon, Portugal, noticed that a specific type of ILC referred to as an ILC2 could be found along the axons of neurons in the lungs and gut of mice. As a result, they decided to see whether the two tissues could communicate with one another.

Through their analysis, the researchers determined that ILC2s were outfitted with a defined “receptor” for a neuronal messenger known as neuromedin U (NMU). NMU is only produced in large quantities by neurons, so the researchers knew that it was those cells that were communicating with the ILC2s.

This hypothesis was tested by infecting two groups of mice with a parasite. One group was the control, while the other had been modified to removed the NMU receptors from their ILC2s. While the first group’s ILC2s could trigger a response to the infection, the second group’s could not.

The researchers concluded that the neurons were essentially providing the immune cells with an “adrenaline rush” that prompted them to take immediate action against the infection.

“[N]eurons define the immune cells’ function. Nobody could have imagined that the nervous system coordinates, commands, and controls the immune response throughout the whole organism,” IMM researcher Henrique Veiga-Fernandes told AR Magazine. “It’s one of the fastest and most powerful immune reactions we have ever seen.”

More to Know

While we’ve known about ILCs for a while, new research like this study out of Portugal can help us understand exactly how they interact with the nervous system.

Scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine just published a similar study on ILC2s, and senior author Dr. David Artis is optimistic that this knowledge of how the nervous system responds to infections could one day be used to develop new therapies to treat inflammatory diseases.

“Where we are most excited is thinking about multiple chronic inflammatory diseases that might be related to this neuronal-immune axis and where we might be able to intervene,” he explained in a press release published by the school.

Eventually, we may be able to use what we learn about ILCs and NMU to help people affected by asthma, food allergies, inflammatory bowel disease, and numerous other conditions, but right now, more research is needed.

“In humans, ILC2s also have NMU receptors,” noted Veiga-Fernandes. “But we are still very far from understanding how we could safely use this neuro-immunological ‘bomb’; for now, we are at the fundamental research level.”