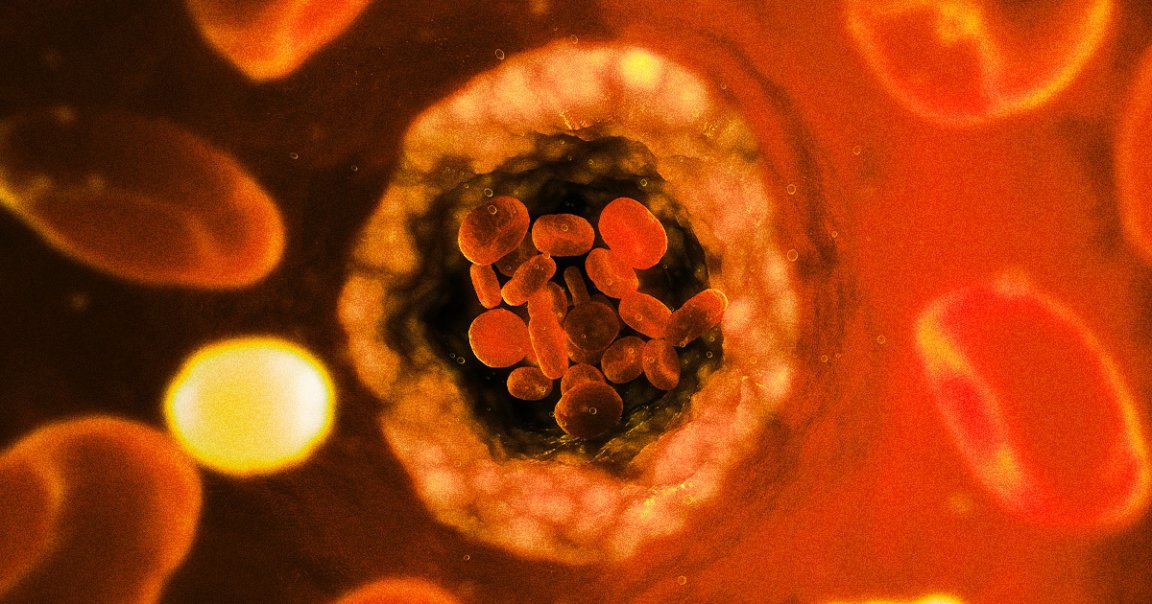

A new study has linked the presence of microplastics in artery-clogging plaque to a higher risk of heart disease and even death.

From remote regions of Antarctica and layers of sediment untouched by humans to human hearts and even newborn human babies, microplastics are everywhere. But while it stands to reason that microscopic shards of chemical-laced fossil fuel polymers finding their way into every imaginable corner of life probably wasn’t great, there hadn’t yet been an established link to its measurable impacts on the human body.

Until now, that is. Published this week in The New England Journal of Medicine, the “landmark” study, conducted by a team of Italian researchers, is the first of its kind to establish a connection between the presence of microplastics in the human body and its impact on human health.

According to the research, this was also the first time that microplastics were discovered in artery-clogging plaque at all.

“This is a landmark trial,” Robert Brook, a physician-scientist at Wayne State University who studies the relationship between cardiovascular disease and the environment, told Nature. (Brook was not involved in the study.) “This will be the launching pad for further studies across the world to corroborate, extend, and delve into the degree of the risk that micro and nanoplastics pose.”

The study followed 257 participants, all of whom had fatty plaques removed from their carotid arteries — in short, the blood vessels in the neck that carry blood between the head and the heart — between the years 2019 and 2020. Polyethylene, the most widely-used plastic in the world, was detected in the “carotid artery plaque of 150 patients,” according to the study.

“Electron microscopy revealed visible, jagged-edged foreign particles among plaque macrophages,” it continues, “and scattered in the external debris.”

The scientists continued to follow the patients for 34 months, ultimately finding that those with microplastics present in their arteries were nearly five times more likely to suffer a heart attack, stroke, and in the most serious cases, even death.

“It’s extraordinary,” cardiologist Eric Topol, who was not involved in the study, told USA Today of the findings. “I’m a cardiologist for three decades plus and I never envisioned we’d have microplastic in our arteries and its presence would accelerate arteriosclerosis.”

To be clear, this study is still observational. It doesn’t prove a solid correlation between the presence of microplastics and incidents of cardiovascular emergency or death, though some doctors believe that microplastic-induced inflammation — long-term inflammation is considered a major driver of cardiovascular disease — may play a role.

“This is as good a smoking gun for plastics as we’ve seen,” Topol told USA Today. “They basically connected the dots — the presence of the plastic in the arteries, profound inflammation and then events such as stroke, heart attack and death. They had it all.”

To that end, researchers across the board seem to concur that the results of this study are more than enough to warrant further research into the influence of microplastics on the human body, not to mention further grappling with questions of humanity’s relationship with petroleum products and their impact on the environment around us — and, it seems, their impact on our bodies in turn.

“Although we do not know what other exposures may have contributed to the adverse outcomes among patients in this study,” Philip Landrigan, a Boston College pediatrician and epidemiologist, wrote in an editorial that accompanied the study’s release, “the finding of microplastics and nanoplastics in plaque tissue is itself a breakthrough discovery that raises a series of urgent questions.”

More on microplastics: Scientists Puzzled to Find Plastic Fragments Inside Human Hearts