A common skin bacteria could be the next tool against cancer, scientists have discovered.

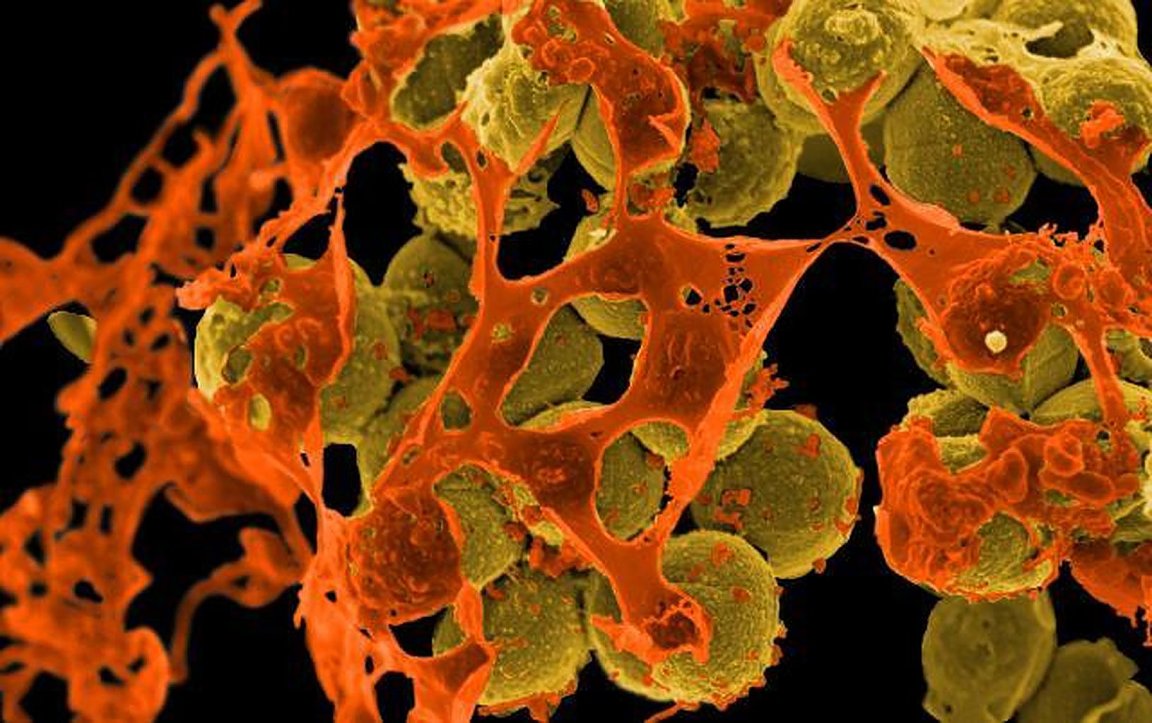

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) were screening a strain of the familiar bacteria Staphylococcus epidermidis, to explore its ability to attack harmful bacteria — and found it has the potential to do much more than that.

This particular skin microbe fights off its enemies by producing a substance — called 6-N-hydroxyaminopurine (6-HAP for short) — that prevents its target’s DNA from replicating, the researchers observed. Fascinated by the these properties, they decided to test whether it could be put to other uses.

Study co-author Richard Gallo from UCSD told the The Guardian, “[…] When we identified the nature of the chemical produced by this strain, we proceeded with experiments to determine if it might have activity against tumors.”

Gallo added that the bacteria strain might be used therapeutically to inhibit the growth of various forms of cancer.

His team, which recently published its findings in the journal Science Advances, tested the hypothesis on animals, administering the 6-HAP substance for two weeks to a group of mice affected by a type of skin cancer.

The treated mice developed tumors that were roughly 60 percent smaller than their counterparts that had not received the treatment. 6-HAP also seemed to protect the animals from the damages associated with exposure to ultraviolet light — they developed smaller tumors, and a greater number of mice didn’t get sick at all. Gallo and his team were also encouraged by the fact that the substance also did not seem harmful to the animals.

“This unique strain of skin bacteria produces a chemical that kills several types of cancer cells but does not appear to be toxic to normal cells,” he told MedicalNewsToday.

According to the American Academy of Dermatology, skin cancer is the most common form of cancer in the U.S. One in five Americans will develop the disease in their lifetime; 9,500 people that are diagnosed with the condition every day in the U.S. alone. Gallo’s work adds to a growing body of research that provides medical professionals with inroads to additional options for skin cancer treatment.

Julian Marchesi, professor of human microbiome research at Cardiff University, who was unaffiliated with the study, was excited by these findings. He told The Guardian, “The next stage of this exciting work will be to translate it to human clinical trials and show that this bacterially produced chemical can protect the host from skin cancer.”