Lots of sleep. Vitamin C. Chicken soup.

Yes, having a cold sucks. But after roughly 3,000 years, that’s the best treatment we’ve come up with.

Soon, though, we might not be so defenseless against the nasty viruses that leave us achy, stuffy, sniffly, and sneezy.

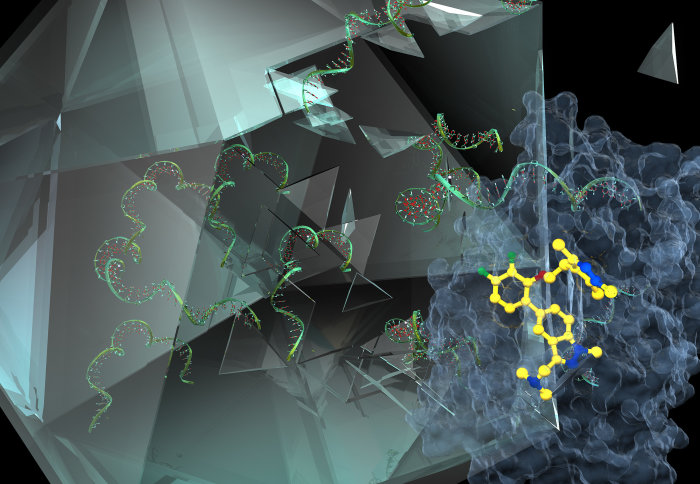

Researchers at Imperial College London (ICL) have developed a new molecule that doesn’t target cold symptoms or even the virus itself: it affects the cells in our bodies that betray us when we catch a cold. They published their research yesterday in Nature Chemistry.

The common cold is notoriously difficult to treat because hundreds of different viruses can cause it. A treatment that works against one strain might not work against another. As if that’s not bad enough, the viruses are evolutionary ninjas. Even if we figure out a way to treat one strain, it will inevitably evolve until the treatment is no longer effective.

That’s almost as annoying as the cold itself.

Today, we can’t treat the actual virus — we’re left trying to nurse the symptoms. We essentially throw up our hands and let the virus do what it will, counting on our immune systems to take its time to knock it out while we down NyQuil and gargle saltwater to feel better.

The ICL team decided to take a unique approach to the problem: If we can’t directly take down every cold virus (and every potential cold virus), maybe we can make the human body inhospitable for those viruses.

When a cold virus enters the body, it commandeers a human protein cell called N-myristoyltransferase (NMT). The virus uses this protein to construct a capsid, a shell that protects the virus so it can replicate.

The ICL team developed a molecule, IMP-1088, that completely blocked several strains of rhinovirus, the primary cause of the common cold, from reaching the NMT protein.

Since all viruses use NMT in the same way, the team expects IMP-1088 would translate to any other strains as well.

This isn’t the first attempt to tackle the cold by targeting the human cells that make colds possible. The only problem? Those approaches proved toxic to human cells. So far, in experiments done on human cells in the lab, IMP-1088 has shown no negative effect on the human cells, so the team hopes to move to trials in animals, and then in humans.

The researchers don’t note how long these trials could take, but we’ve waited roughly three millennia for an effective cold treatment. It’s gotta be less time than that.