Living on Earth is pretty cool. Here, we have several defense mechanisms to help keep the bad energy — such as gamma rays and cosmic rays — out , while letting the good energy, — like visible light — in. For scientists who like to study these more dangerous forms of energy, Earth is a party pooper. This is why some scientists at the University of Southampton in England are turning to Earth’s closest cosmic neighbor; the Moon.

These scientists are looking to study Ultra High Energy (UHE) cosmic rays. These cosmic rays are very exotic and very mysterious. They have incredible amounts of energy, and nobody knows where it comes from. Their kinetic energy is insane, with energy that is several orders of magnitude greater than other types of cosmic rays. On Earth, we can detect these particles at an average rate of less than one particle per square kilometer per century. This is fantastic news for life, since these UHE cosmic rays would be very bad for us. Daredevil scientists, on the other hand, need to figure out another way to study these particles.

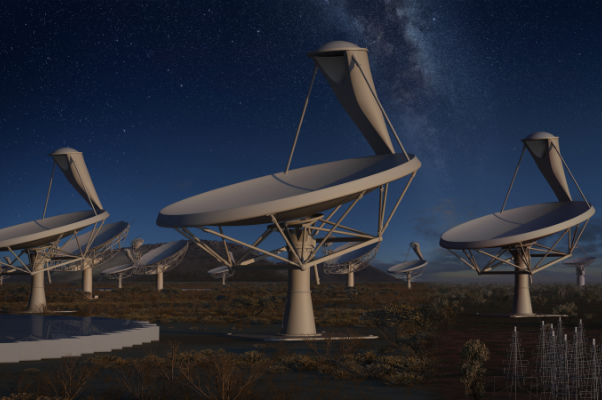

This is why Dr. Justin Bray, who is a research fellow at Southampton in the field of Cosmic Magnetism, has created a proposal to use the Square Kilometer Array (SKA), which will be the largest and the most sensitive radio telescope in the world, to monitor the Moon allowing us to detect many more UHE events than we can here on Earth. Currently, the only way to study these cosmic rays is to watch their remnants after they are destroyed in the upper atmosphere.

This is very hard to find because these cascading events happen really close to our Earth bound radio telescopes, they have a hard time monitoring an area large enough to see these events with any type of regularity. When observing the visible surface of the moon, scientists have an area millions of square kilometers to play with. Only problem is, the incomplete SKA is the only telescope that’s sensitive enough to actually detect the cascade of secondary particles that come from a UHE cosmic ray hitting something.

When the SKA is complete, researchers will have the ability to observe many more UHE events, about 165 events per year (as compared to the current 15 or so events per year). By observing these events, scientists hope to answer some of the questions revolving around these cosmic rays, such as, where do they come from?

The SKA is scheduled to be complete and operational in the early 2020s and it will help advance our understanding of the universe’s evolution.