The Mona Lisa may very well be one of the most recognizable faces in the history of humankind. And no small thanks are owed to Leonardo da Vinci (one of the most talented and celebrated painters of all time) for choosing to plaster her face on a canvas, which had an insurance assessment value of US$100 million in 1962 (US$740 million in today’s dollars). Now, Mona Lisa has gone ET. Not physically of course, but digitally.

Team members from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, MD, sent a digitized copy of Mona Lisa approximately 240,000 miles (390,000 kilometers) from Earth in orbit around the Moon, using a series of laser pulses, which are routinely sent to track the position of the Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter (LOLA) on NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO). The LRO has been collecting data from the lunar poles since 2009.

In order to accomplish this feat, the image was divided into 30,400 pixels, arranged as an array of 152 pixels by 200 pixels. Each pixel was converted to a shade of corresponding to a number between 0 and 4,095. At that point, each pixel was transmitted to LOLA by a laser pulse, with each pulse being fired in one of 4,096 possible time slots over the course of a brief time window, allotted for tracking the laser beams. The data was transmitted at a rate of approximately 300 bits per second, until the complete image had been sent. Then, LOLA reconstructed it using the arrival times of each of the corresponding laser pulses from Goddard.

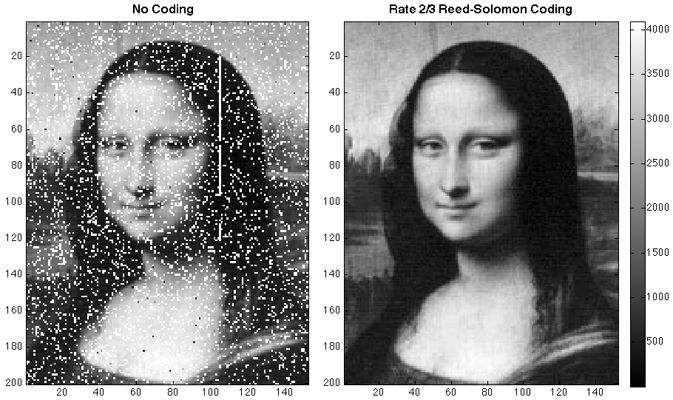

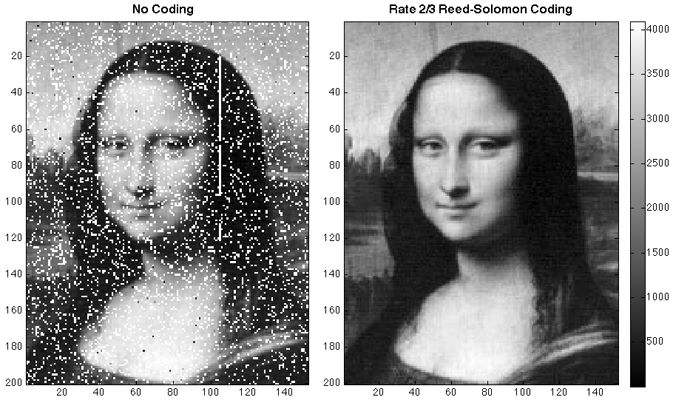

As you can see in the first image of the Mona Lisa, portions of the transmissions we received back on Earth by radio telemetry are off; this is due in large part to unexpected turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere (the large white stripe running down the first image was created during a brief transmission pause). So the team employed Reed-Solomon coding, an error-correction algorithm often used in both CDs and DVDs to overcome some of these fluctuations (which can be seen in the second image).

Let me go ahead and mention the proverbial elephant in the room. Why do this? Why waste any time or perceived resources beaming an image to the Moon? It might sound kind of silly, but this experiment may wind up being very important in developing lasers that may be used as a backup to our current communication technology. This was the first instance that scientists have successfully achieved one-way laser communication at planetary distances, according to principal investigator David Smith of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Perhaps in the future, this technology may lead the way to developing some sort of a “live” high-definition feed of distant planetary bodies in our Solar System. I don’t know about you, but I would definitely subscribe to a Jupiter-cam. She has a pretty decorated atmosphere which is always up to all kinds of interesting things.