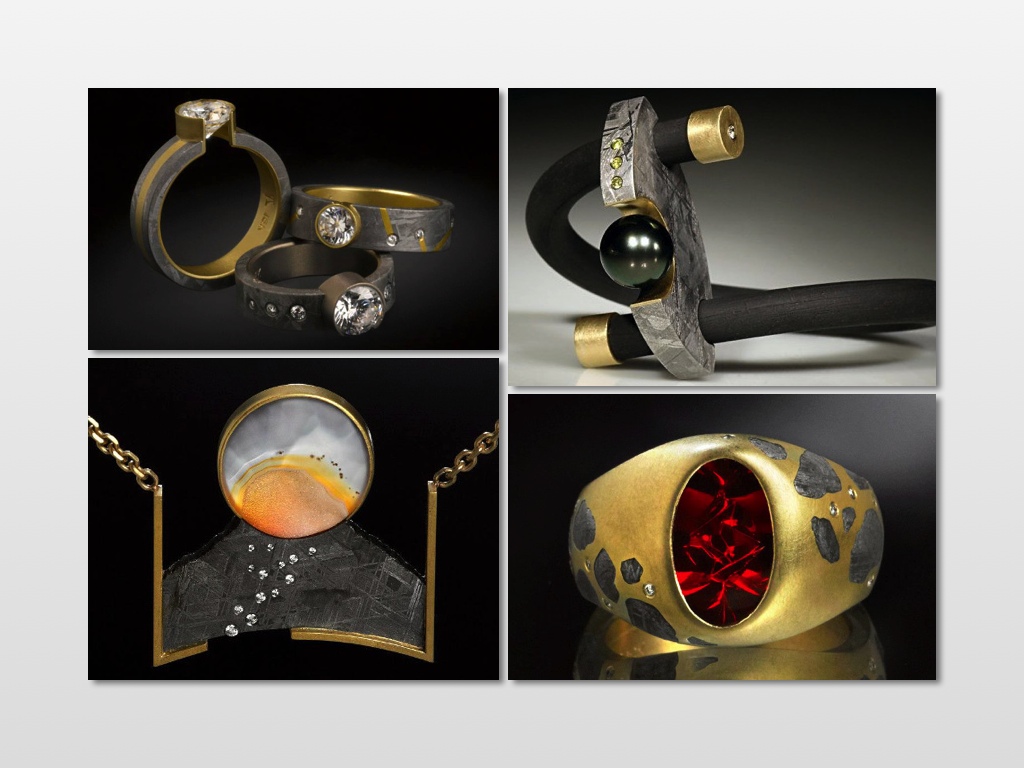

Meteorites have been incorporated into jewelry for at least 5,000 years. Beads on an Egyptian necklace are in fact the very first use of iron on record, and their source almost certainly fell from space. The meteorite beads were strung alongside gold, agate, and other gemstones—a combination of materials much like what’s on display above in a collection of jewelry produced by Jacob Albee.

I recently asked Albee how he came to work with such an unusual material: I was gifted a piece of Gibeon meteorite when I was working for another jewelry designer who saw it at a gem show. I thought it was the coolest thing I had ever seen.” He had been given part of a massive meteor* that fell over prehistoric Namibia, fragmenting into thousands of pieces as it plowed through the atmosphere. The fragments were dispersed over 20,000 square kilometers, an area known as a “strewn field”, near the town of Gibeon. An astounding 26 tonnes of material has been recovered from this single fall.

Iron-Nickel Crystals:

Gibeon meteorite is popular among jewelers because of its nickel-iron crystals, referred to as Widmanstätten patterns or, less commonly, Thompson structures. Thompson actually made the discovery first by 4 years in 1804, but he died shortly thereafter and the Napoleonic wars prevented his work from becoming widely known until much later. Since Widmanstätten also has a lunar crater and an asteroid named for him, I’m going to stick with Thompson from here on.

Thompson structures are interleaving bands of two different iron-nickel alloys that differ in their respective nickel contents—lower for kamacite (~10%) and higher for taenite (20%+). If a meteoroid* forms with an intermediate level of nickel and cools over millions of years (no less!), the two alloys will separate into the crystalline pattern seen in Albee’s jewelry. The extent to which Thompson structures are visible is actually the basis of the original classification scheme for meteorites:

- Hexahedrites (H): less common, not enough nickel for Thompson structures to form.

- Octahedrites (O): most common, further differentiated based on crystal thickness.

- Ataxites (D): rarest, too much nickel for Thompson structures to form.

Gibeon meteorites are classified as a “fine” octahedrites because their crystals are on the thin side, between 0.2 and 0.5 millimeters. This, along with their relative abundance, makes them ideal for jewelry.

Becoming Jewelry:

Before becoming a lovely adornment, the meteorites start as thin slabs or blocks on Albee’s workbench. These are generally smaller than a postcard or a brick, sometimes with and sometimes without the natural edge. The jewelry-to-be dictates how the meteorite is shaped. “Surface curves like domed rings are done by removing material, but the bodies of the rings and bracelets are annealed and bent, sometimes cold-forged, and occasionally even rolled.”

These processes can be more difficult with meteorite because of its increased hardness compared to traditional fine metals. Shaping and stone setting require more effort, which can sometimes cause the inhomogeneous material to crack. “Meteorite is also filthy compared to gold, so heating, cleaning, and finishing are much more involved than with fine metal pieces.” Once the meteorite has been properly shaped and cleaned, it’s finished with an acid treatment (etched) to reveal the Thompson structures. This works because one of the iron-nickel alloys in the meteorite (kamacite) is less resistant to erosion from acid than the other (taenite).

A Personal Note:

Albee is among a fairly small number of people that do high-quality work with meteorite. I came across his website 3 years ago via a Google search for “meteorite engagement ring.” I must admit that I’m not overly fond of the engagement ring concept or the history behind it. That industry has a poor ethical and environmental track record, to say the very least, and I wasn’t enthusiastic about contributing to it. So in addition to getting an awesome space ring, it was important to me that Albee was willing to set a non-traditional gemstone (Moissanite) and that he uses recycled materials. (He also uses ethically sourced diamonds, but I was intent on avoiding them either way.) I didn’t know it when he made my wife’s ring (pictured on the right), but this ethos stems in part from a love of the natural sciences.

In addition to a fine arts degree, Albee holds a B.S. in wildlife biology. He was headed for a post-graduate degree in raptor biology before a summer job turned jewelry design into a long-term pursuit. His outlook on the environment was well put in a radio interview with PRX:

“I’m concerned about species loss, I’m concerned about climate change, I’m concerned about overpopulation. To leave the house and go to work, and have work be, ‘I’m going to go take $2,000 worth of gold that came out of a giant destructive hole in the ground, and then I’m going to set some diamonds that came out of another giant destructive hole in the ground into that gold, and then I’m going to sell it…’ It can taste a little bitter. The other side of that is, you know, it’s great to put pressure on me to be the most ethical businessperson I can. Jewelry is not just an expression of someone’s vanity. It is a viable art form. It enjoys a rich history and a history I’m proud to be a part of.”

Visit JacobAlbee.com for further information and their Facebook page for more pictures and new additions. The slideshow photographs were taken by Alex Williams, Michael Snipe, and Rick Levinson (see captions for individual credits).

*Space rock jargon can be confusing. Click here to learn about the distinction between meteor, meteorite, and meteoroid.