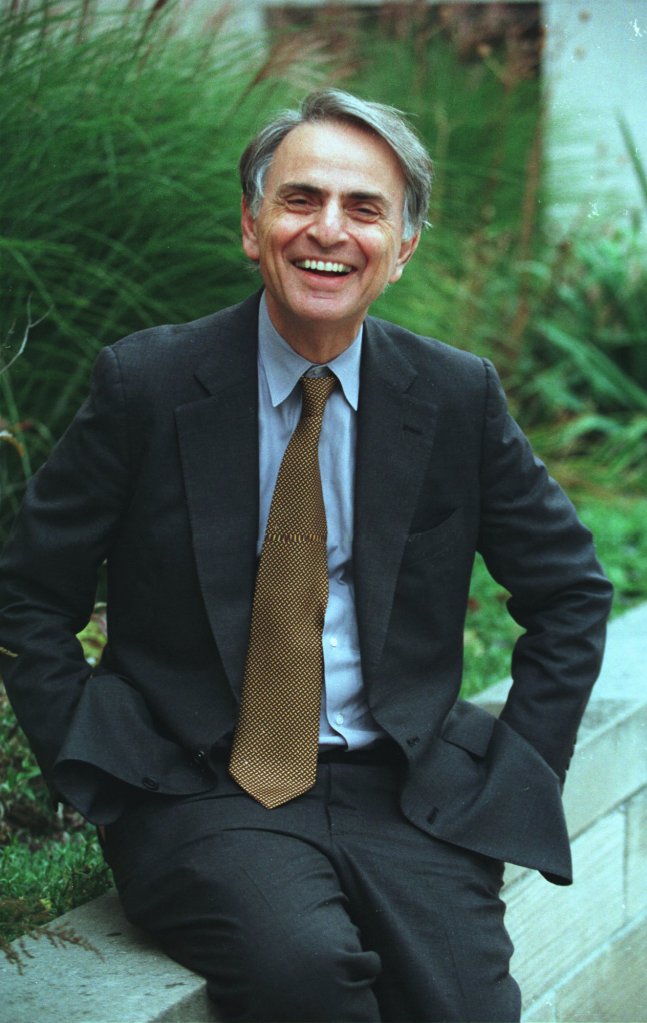

If you have even the most remote interest in astronomy, it’s likely Carl Sagan’s name has came up an uncountable number of times in your research on the subject. Though he passed away years ago, his words are splashed on letterheads, his quotes inked into the skin of science enthusiasts all over the globe, and his influence can still be seen floating on the outskirts of our solar system, in two golden records that are destined to be the first man-made objects to break free from the sun’s influence, allowing the discs to roam freely in the spaces between stars for eternity, perhaps.

A Brief Biography:

Carl was born in Brooklyn, New York to an immigrant from Russia (which is where he inherited his inane curiosity of all things from) and a housewife from New York. Spending most of his childhood in a small town in New Jersey, he set out for Illinois where he attended the University of Chicago.

There, he was a participant in the Ryerson Astronomical Society. During this period, he explored a number of different fields including the arts, astronomy, physics, and planetary science before he ultimately moved to Ithaca, New York to direct the Laboratory for Planetary Studies at Cornell University.

Beforehand, he was heavily involved in NASA’s space program, where he worked as an adviser. His duties included briefing the Apollo astronauts that were to be the first people to step foot on an extraterrestrial body, contributing towards the construction and subsequent experiments done by robotic spacecrafts sent to explore the solar system, investigating radio emissions from Venus to accurately determine its surface temperature and taking part in the research, management and development of the first Mariner mission to Venus in the early 1960’s.

A Brief Summary of his Many Accomplishments:

Despite his grocery list of accomplishments, Carl Sagan is primarily known for his devout passion for science, and he dedicated much of his life to advocating science literacy whilst making complex topics interesting and fun to children as well as the general public.

His most prominent contribution to science literature is his award, winning thirteen-part PBS television series, “Cosmos: A Personal Voyage” (which is available on Netflix’s Instant Watch, among other video sites. Cosmos was remade with Neil deGrasse Tyson as the host and released in 2014).

Cosmos was wildly popular, which eventually led to him writing a book on the topic, which was one of the best selling science books in history, selling more than 5 million copies whilst remaining on the New York Times’ Best Seller list for 70 consecutive weeks.

Besides “Cosmos,” he also wrote several other books including (but not limited to): “Pale Blue Dot,” “Contact,” “The Demon Haunted World,” “Dragons of Eden,” “Billions and Billions,” “Broca’s Brain” as well as writing the introduction to Stephen Hawking’s best selling book, “A Brief History of Time.”

Death and Legacy:

Carl passed away on December 20th, 1996 after a vicious bout of pneumonia. He was just 62 years old. He had three bone marrow transplants in the years leading up to his death after suffering from myelodysplasia. At the time of his death, he was father to five children born from three of his wives. At the time, he remained married to Ann Druyan. Several years after Carl passed on, she had this to say about him, and I believe it summarizes how much he meant– not only to the world, but to his family as well.

When my husband died, because he was so famous and known for not being a believer, many people would come up to me-it still sometimes happens-and ask me if Carl changed at the end and converted to a belief in an afterlife. They also frequently ask me if I think I will see him again. Carl faced his death with unflagging courage and never sought refuge in illusions. The tragedy was that we knew we would never see each other again. I don’t ever expect to be reunited with Carl. But, the great thing is that when we were together, for nearly twenty years, we lived with a vivid appreciation of how brief and precious life is. We never trivialized the meaning of death by pretending it was anything other than a final parting.

Every single moment that we were alive and we were together was miraculous-not miraculous in the sense of inexplicable or supernatural. We knew we were beneficiaries of chance. . . . That pure chance could be so generous and so kind. . . . That we could find each other, as Carl wrote so beautifully in Cosmos, you know, in the vastness of space and the immensity of time. . . . That we could be together for twenty years. That is something which sustains me and it’s much more meaningful. . . . The way he treated me and the way I treated him, the way we took care of each other and our family, while he lived. That is so much more important than the idea I will see him someday. I don’t think I’ll ever see Carl again. But I saw him. We saw each other. We found each other in the cosmos, and that was wonderful.

Fun Fact: A “Sagan” is defined as a unit of measurement that’s equal to at least four billion. Carl frequently used “billions and billions” in his literature, and he stressed the “b” when saying “billions” in his speech. So much, in fact, that the phrase landed him a tribute that’s still used today. [As an example: It is estimated that the Milky Way galaxy has 100 Sagan (400,000,000,000) stars.]