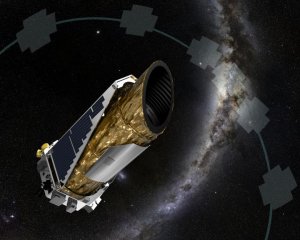

Since Kepler Space Telescope took to the skies in early 2009, it has identified more than 4,000 exoplanetary candidates, ranging from small, rocky worlds, to large gaseous bodies. For all intents and purposes, it was our best shot at finding Earth 2.0. That is, until 2013, when — around 4 years into its extended 7 year mission — a terrible fate befell the revolutionary observatory. Two of its four reaction wheels, which are used to keep the spacecraft in a fixed position, failed, putting a big question mark over the future of Kepler. However, Kepler became ‘the little telescope that could’ when it was repurposed months later, with a new prerogative.

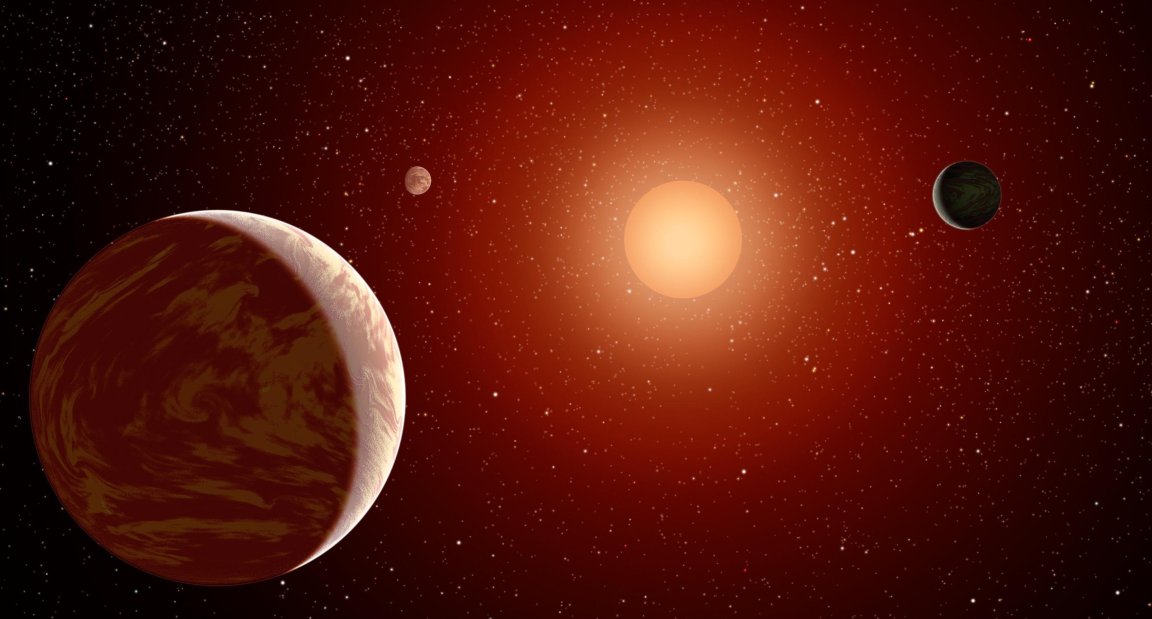

For the second time this year, Kepler has proven that it got its groove back. This time, it discovered three planets circling a nearby star. All are believed to be a little bit larger than Earth, and one even orbits its parent star from the habitable zone, defined as the region in which a planet’s surface might retain water in liquid form.

The star itself, called EPIC 201367065 (we’ll just call it EPIC), is a red dwarf about 150 light-years from Earth, with about half the Sun’s mass. It’s also drastically cooler and much more dim, which make it a suitable target for Kepler’s new mission. In fact, Kepler was able to study the atmosphere of each planet, and to deduce whether they might be suitable for life.

According to Ian Crossfield, the study’s author, “A thin atmosphere made of nitrogen and oxygen has allowed life to thrive on Earth. But nature is full of surprises. Many exoplanets discovered by the Kepler mission are enveloped by thick, hydrogen-rich atmospheres that are probably incompatible with life as we know it,”

A Closer Look at the Planets:

The smallest and most distant planet in the EPIC-201 system is around 1.5 times the size of Earth, and it orbits EPIC from a distance small enough that it receives almost the same amount of light Earth gets from the Sun. The other two are 2.1 and 1.7 times the size of Earth, and they receive 10.5 and 3.2 times the light Earth receives.

“Most planets we have found to date are scorched. This system is the closest star with lukewarm transiting planets,” remarked Erik Petigura, the UC Berkeley graduate student who found the planets after analyzing Kepler’s data, “There is a very real possibility that the outermost planet is rocky like Earth, which means this planet could have the right temperature to support liquid water oceans.”

Of course, there are a number of things other than size, starlight and a balmy surface temperature that must be taken into consideration before a planet can be deemed habitable. These things include, an appreciable atmosphere, a steady magnetic field, a mostly-circular orbit that doesn’t take it too close or too far away from its star, and a whole host of other things we probably haven’t thought about yet. So essentially, what we do know is cosmetic. One thing is clear though, we are well on our way toward finding a truly habitable world, and this system, in particular, will shed light on how Earth-like ‘Earth-like’ worlds really are.

Andrew Howard, an astronomer from the University of Hawaii, comments, “We’ve learned in the past year that planets the size and temperature of Earth are common in our Milky Way galaxy,” he continued, “We also discovered some Earth-size planets that appear to be made of the same materials as our Earth, mostly rock and iron.”

Additionally, “This discovery proves that K2, despite being somewhat compromised, can still find exciting and scientifically compelling planets,” Petigura said. “This ingenious new use of Kepler is a testament to the ingenuity of the scientists and engineers at NASA. This discovery shows that Kepler can still do great science.”

After Petigura found the planets in the Kepler light curves, the team quickly employed telescopes in Chile, Hawaii and California to characterize the star’s mass, radius, temperature and age. Two of the telescopes involved, the Automated Planet Finder on Mount Hamilton near San Jose, California, and the Keck Telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, are University of California facilities.

The next step will be observations with other telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope, to take the spectroscopic fingerprint of the molecules in the planetary atmospheres. If these warm, nearly Earth-size planets have puffy, hydrogen-rich atmospheres, Hubble will see the telltale signal, Petigura said.

The discovery is all the more remarkable, he said, because the Kepler telescope lost two reaction wheels that kept it pointing at a fixed spot in space.

Kepler was reborn in 2014 as ‘K2’ with a clever strategy of pointing the telescope in the plane of Earth’s orbit, the ecliptic, to stabilize the spacecraft. Kepler is now back to mining the cosmos for planets by searching for eclipses or “transits,” as planets pass in front of their host stars and periodically block some of the starlight.

“This discovery proves that K2, despite being somewhat compromised, can still find exciting and scientifically compelling planets,” Petigura said. “This ingenious new use of Kepler is a testament to the ingenuity of the scientists and engineers at NASA. This discovery shows that Kepler can still do great science.”

Kepler sees only a small fraction of the planetary systems in its gaze: only those with orbital planes aligned edge-on to our view from Earth. Planets with large orbital tilts are missed by Kepler. A census of Kepler planets the team conducted in 2013 corrected statistically for these random orbital orientations and concluded that one in five sun-like stars in the Milky Way Galaxy have Earth-size planets in the habitable zone. Accounting for other types of stars as well, there may be 40 billion such planets galaxy wide.

The original Kepler mission found thousands of small planets, but most of them were too faint and far away to assess their density and composition and thus determine whether they were high-density, rocky planets like Earth or puffy, low-density planets like Uranus and Neptune. Because the star EPIC-201 is nearby, these mass measurements are possible. The host star, an M-dwarf, is less intrinsically bright than the sun, which means that its planets can reside close to the host-star and still enjoy lukewarm temperatures.

According to Howard, the system most like that of EPIC-201 is Kepler-138, an M-dwarf star with three planets of similar size, though none are in the habitable zone.

[Reference: University of Arizona]

The paper that outlines their findings, “A Nearby M Star with Three Transiting Super-Earths Discovered by K2,” has been submitted to the Astrophysical Journal and can be read in full here.