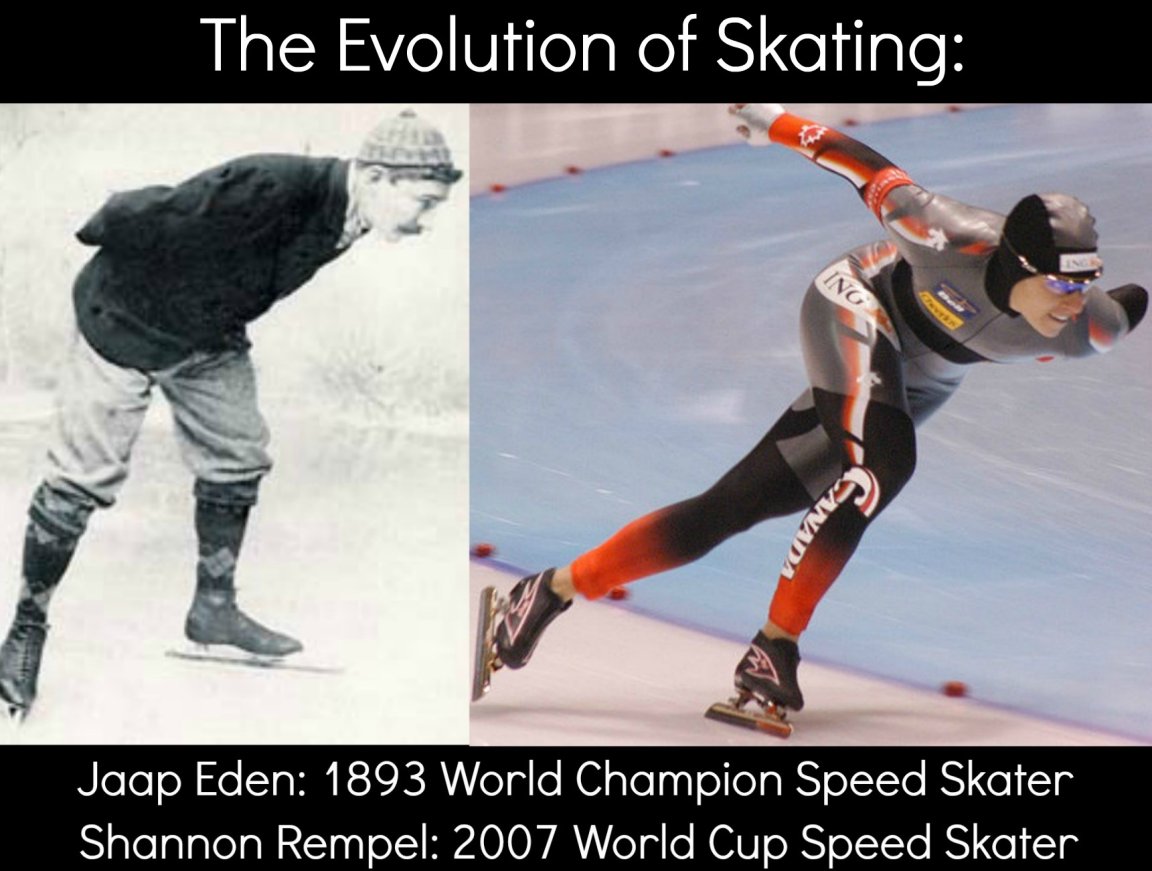

As the Olympics draw to a close, it is a good time to check out the science behind the key equipment in long track speed skating – the skate! There is a long history to the ice skate, about 4000 years of it; however, any truly scientific development is more recent. Let us have a look at a particularly interesting time in the 1980s and 1990s. For almost a century, skates were not much more than a pair of simple, sharp, iron strips. Major improvements were made – improvements that would change the world of speed skating forever!

The Idea

In 1981 a study was started by Gerrit Jan van Ingen Schenau, of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, into the apparent problem with skaters not being able to properly extend their ankles for fear of digging the tips of the skates into the ice. The digging would force the skater to slow down, causing them to fall and even cost them the race. Ankle movement is a large part of gaining speed in most other leg-powered sports and allowing skaters to do the same would be an enormous benefit.

In the next few years, van Ingen Schenau studied the leg and the ankle movements in top level skaters as well as other athletes. High jumpers in particular, as they have a very typical ankle extension at the last stage of their push off the ground. As the leg extends, the knee will straighten naturally. However, this straightening will make the foot move “slower” near the end of the stroke, moving parallel to the intended motion when the knee is bent at 90° and as the knee straightens (approaching 180°) the foot will be at nearly a right angle. To compensate, high jumpers will extend the foot down when the leg is nearly straight, again adding a more vertical component to the force that is pushing them up. Unable to do this, skaters lose contact with the ice before the knee is entirely straight, resulting in energy loss.

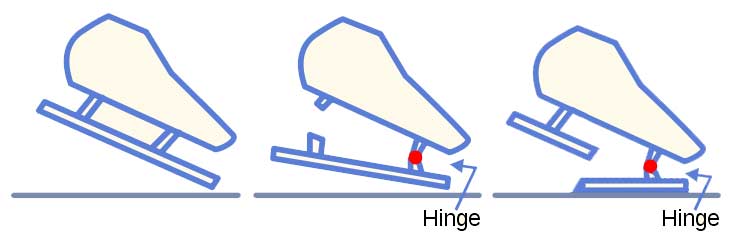

How is this corrected? By making the blade on the skate able to pivot under the ball of the foot, allowing the skater to extend the ankle while the blade stays more parallel to the surface of the ice. So the front strut of the blade was given a hinge, the back strut cut in two and thus the Clap Skate was born.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons / Author: Max Dohle

That name is not, as you might expect, because of the noise the skate makes, but derived from the original Dutch name “Klapschaats“, which roughly translates to “clap on extra speed”.

The Results

The group around van Ingen Schenau had the skates ready for the 1984/85 season and the first official time was set in February ’85 in a 500 meter race. In 1987 the skates went into production and quite a few test skaters started using them. They all immediately realized the benefits of the new skates but surprisingly all fell back on their old techniques in important races; the skates falling to the wayside.

Originally the test skaters were all over 25 years old, so new skates were handed out to 11 junior riders. They trained with them and competed for placement in national championships in the Netherlands for the 1994/95 season. The skaters using the standard Nordic skates with the fixed blade, improved on average 2.5% compared to their previous season. The group with the clap skates improved over 6%Of the 11 juniors in the test group, 10 advanced to the championships.

The results for the juniors finally got a number of the top-level women skaters interested. Of those women, Tonny de Jong won the 1997 European Championships. She beat Gunda Niemann, the East German skating legend, who was pretty much unbeatable. Gunda Niemann, in turn, called for a ban on the clap skates. She did not succeed (much to her own advantage). The next year, in Nagano, Japan, the winter Olympics saw one world record after world record being shattered. Right in the thick of it was Niemann, now sporting clap skates.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons / Author: McSmit

Clap Skates, as of Late

At the moment a manufacturer is working on skates with the blades consisting of two separate halves, the duoschaats (duo skate, linked article in Dutch). Only the front half hinges, which should (hypothetically) gain the skater some extra bite on the ice and several tenths of a second on the start. Sure, gaining a few tenths at the start it great, but the skates will not do the job if that is the only benefit. Any misalignment between the two blades will throw an elite skater off his or her game.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons / Author: Stijn Veeger

As for the science behind the principle of the clap skate, a few years ago a new study (article in Dutch) was done, financed by the Dutch Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). As it turns out, the original hypothesis was not correct even though it seemed to pan out. Researchers invited the ten top skaters for a study where they compared the power generated by them while skating on the classic Nordic skates versus on the clap skates. Indeed the tips of the classic skates scratched through the ice but that did not cause a significant loss of power. The actual difference was measured in the point around which the foot pivots. With clap skates this point is transferred to the ball of the foot instead of out in front of the toes, at the tip. Meaning, the skater can make the ankle extension easier and faster, much like using a smaller gear on a bicycle.

A Few Final Tidbits

The clap skate has revolutionized the sport of speed skating. Today, it is inconceivable that anyone could win a championship without them. Clap skate pioneer, Van Ingen Schenau, was able to enjoy the success of his hard work, but only for a short time. A little over a month after the games in Nagano (1998) he died. One of the obituaries read “In the last two winters of his life he brought 46 world records to his name.”