A ROCKY ROAD TO A ROCKY PLACE

The European Space Agency’s (ESA) lander Philae has had a rough ride…and that’s putting it mildly. Almost two years after it first landed on Comet 67 P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, the ESA is now declaring an end to the lander’s mission.

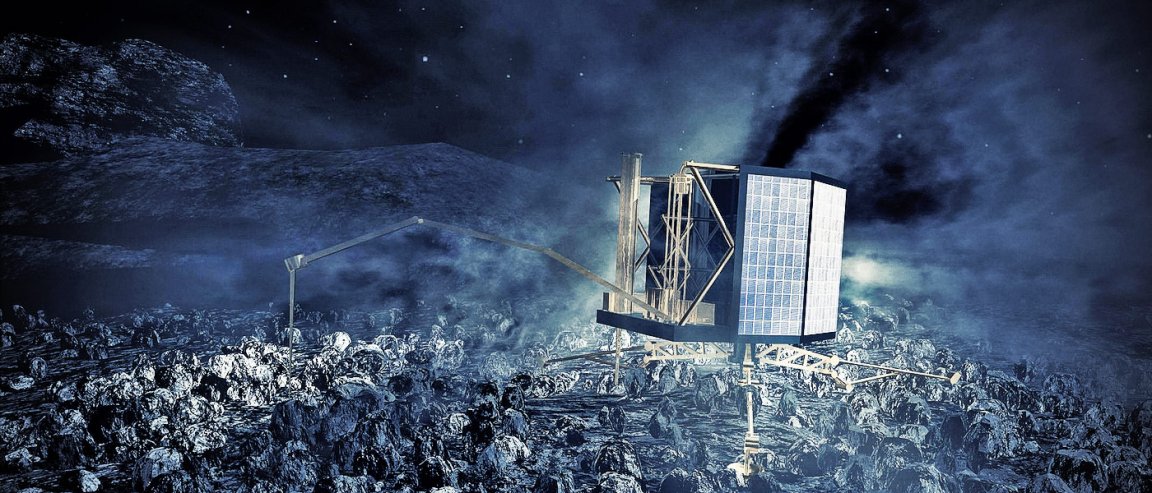

Philae’s mission was to achieve the first landing on a comet and take measurements of the composition of the comet. Accomplishing this task was a feat that challenged the technical and engineering capabilities of the ESA (and again, that’s putting it mildly).

The ESA launched Rosetta, the probe carrying Philae, back in November 2004 so that it would be in the right place at the right time to intercept Comet 67P’s orbit. When Rosetta was in a prime position to carry out its goals, it then launched Philae. The lander hit the comet awkwardly and bounced across the 67P’s surface on November 12, 2014.

After landing, it was scheduled to operate only for three days before it would run out of energy and hibernate. During this period, it was able to give scientists on Earth a truly closeup look at a comet.

Philae’s successful landing allowed scientists to discover that oxygen was present on the comet and realize that frozen water existed on the surface. But all wonderful things must come to an end.

Last year, the ESA was able to reestablish contact with the lander after the solar-powered spacecraft was able to recharge its batteries, but communication was sporadic and was eventually lost after 26 days. The ESA tried to restart the lander and regain contact with the vehicle, but was sadly unsuccessful, forcing the ESA to officially end Philae’s mission.

LOOKING BACK: DEFYING ALL ODDS

Philae’s journey to Comet 67P was a shot in the dark. Unlike the moon landing and NASA’s Curiosity rover on Mars, ESA engineers had no idea what the landing site would look like.

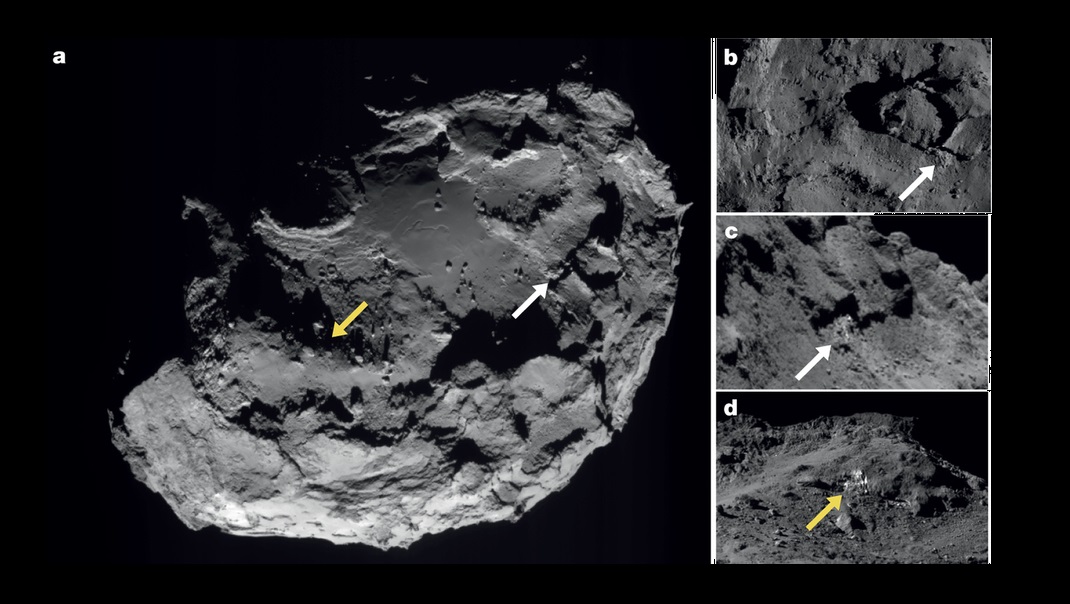

Prior to Rosetta’s mission, little was known of what comets truly looked like, as no spacecraft has ever imaged one up close…or landed on one. When Philae was launched, its landing site was only selected days prior, after Rosetta was able to provide surface images of the comet.

To ensure that Philae would survive the trip, various redundancies had to be built into the lander to account for the possible conditions encountered on the comet. These redundancies showed their worth when Philae ended up bouncing across the surface during it’s landing.

Fortunately, it settled without harm. Unfortunately, it settled in Abydos, an inhospitable region on the comet.

Philae was unable to secure itself to its landing spot because its harpoons were unable to anchor to the ground. Furthermore, ice screws designed to penetrate soft material were unable to penetrate due to the hard surface. As a result, the lander bounced to a location where it was shadowed from the Sun, preventing it from taking advantage of its solar panels.

This is where the engineering team’s planning really paid off. Despite the circumstances the lander was placed in, it was able to operate for a few days using its backup battery. It took measurements of the composition of the comet, surface strength, and magnetic properties while simultaneously imaging the comet and its internal properties. During this operating period, it was able to accomplish nearly 80 percent of the goals set for the project.

Stephen Ulamec, Philae’s lander manager, is proud of their achievement, despite ESA’s decision to declare an end to the project. “What was a bit disappointing was reaching contact again last summer and feeling there was a real chance at getting additional data,” Ulamec says. “The fact that we have a limited lifetime, that’s just how these missions have to be.”

Meanwhile, the Rosetta probe remains in orbit around the comet and will likely enter a lower orbit. Once this occurs, scientists will soon be able to get an image of the lander. So while it seems there will no longer be any communication from the lander, we’ll still be seeing the robotic explorer around.