Astronomers examining data from the James Webb Space Telescope say they’ve spotted what might be the oldest black hole in the universe, born less than a second after the Big Bang.

Their findings, published in a new study awaiting peer review, could offer the best evidence yet of the existence of what’s known as a primordial black hole, a hypothetical object that’s divided scientists for decades.

Potentially far smaller than their modern counterparts — perhaps as tiny as a planet or even an atom — this class of black hole is thought to only have been able to form in the earliest moments of the universe, long before stars and galaxies could come together. That defies our typical understanding that singularities are born from the collapse of large structures, like in a supernova, the violent implosion of a star. And that has huge implications for our understanding of how the universe evolved.

“This black hole is nearly naked,” coauthor Roberto Maiolino, a cosmologist at the University of Cambridge, told The Guardian. “This is really challenging for the theories. It seems that this black hole has formed without being preceded by a galaxy around it.”

Though the findings are stunning, Andrew Pontzen, a cosmologist at University of Durham, cautions that it’s not a smoking gun. They haven’t actually spotted the object existing moments after the universe was formed — since that’s impossible — but some 700 million years after the fact.

“The researchers behind this study use new JWST observations to strengthen the case for primordial origins, but it’s an indirect argument and it will take time for the debate to be settled,” Pontzen told the newspaper.

The typical understanding is that black holes are born from the collapse of massive objects like stars. Some feed on nearby matter and grow to unbelievable sizes, becoming the supermassive black holes found at the center of galaxies. This tidy picture has run into complications, however. We’ve spotted numerous black holes that are so large and ancient that they wouldn’t have had enough time to gain their size simply by starting as the humble byproduct of a star’s death that gradually accretes matter.

That’s led astronomers to speculate about other means of black hole formation. A popular one is that they could be born from the “direct collapse” of incredibly dense clouds of gas, called heavy seeds, that coalesced together through the influence of invisible clumps of dark matter “halos.”

Primordial black holes are considered an even more exotic and disruptive within our current cosmology, because proponents argue that they could only form in the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang, before matter had a chance to spread out evenly and cool down, with some regions being significantly denser than others. Given how early they form in this scenario, it’s possible they could explain how some ancient black holes grew to their impossible sizes — they simply got a headstart. They’re also a potential dark matter candidate, locking away loads of matter in objects too small for detection, the thinking goes.

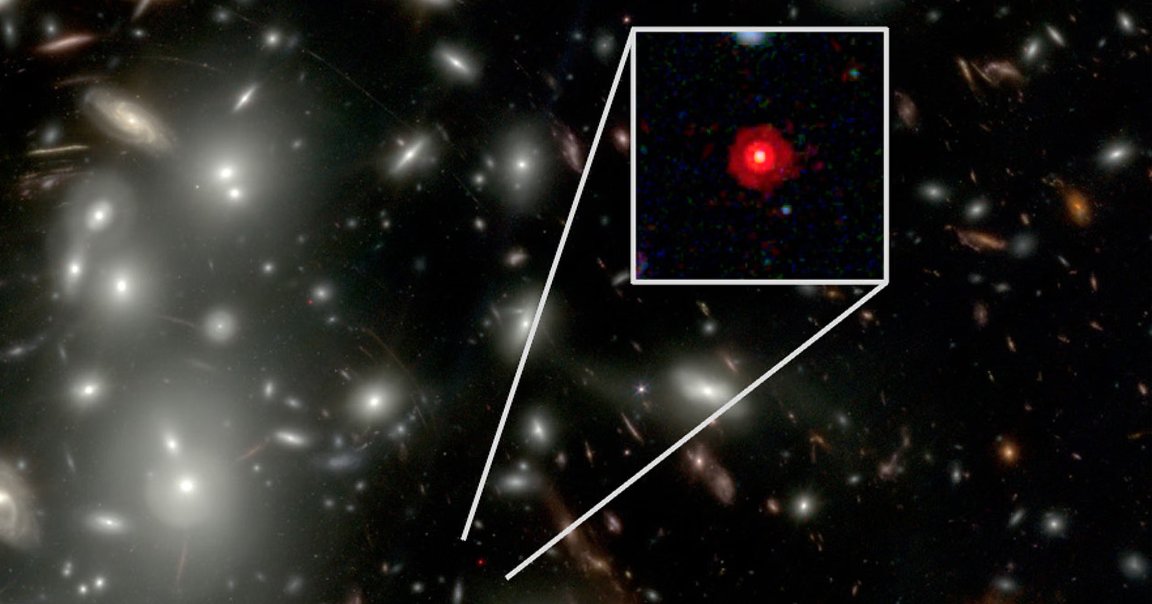

Clues of this latest suspected primordial black hole’s existence lie in a “little red dot” dubbed QSO1, one of a puzzling family of objects that were only spotted when the James Webb first came online nearly four years ago, originating from when the universe was less than a billion years old. Astronomers don’t agree on what the little red dots are, but the leading theories are that the dots, which appear faint to us but must be bright to be visible at all, are an extremely compact form of galaxy, or that they’re active supermassive black holes devouring matter at the center of one.

But the researchers’ observations suggests there’s practically no “galaxy” to speak of here. With the help of gravitational lensing — a magnifying glass-style effect caused by the gravity of a massive object in the foreground — they were able to observe the speed of the material swirling within the dot, a measurement known as a rotation curve. From there, the astronomers calculated that the black hole at the center must be around a staggering 50 million solar masses, or fifty million times heavier than the Sun. Bizarrely, it also contains twice as much mass as its surroundings.

“This is in stark contrast with what we observe in our local universe, where the black holes at the centre of galaxies [like the Milky Way] are about a thousand times less massive than their host galaxy,” Maiolino told the Guardian.

Maiolino previously published another study showing that the matter surrounding the black hole consisted of only hydrogen and helium, the newspaper noted, the first elements that emerged from the Big Bang. Heavier elements were formed later by the collapse of stars, so the fact that we’re not seeing any suggests that the black hole resides in lonely, starless territory.

“Here we’re witnessing a massive black hole formed without much of a galaxy, as far as we can say from the data,” Maiolino told the Guardian. “These results are a paradigm change.”

Again, it’s too early to call it proof of primordial black holes. But it’s tantalizing evidence that could be borne out in the near future.

“A decade from now the next generation of gravitational wave detectors, perfect for sniffing out black holes across the entire universe, will settle the matter,” Pontzen told the newspaper.

More on black holes: Scientists Say Black Holes Could Form Inside Planets, Leading to Absolute Catastrophe