As mysterious as the Big Bang that gave birth to the universe is the brief but tumultuous period that immediately followed it. How did the cosmos transform from a uniform sea of darkness into a chaotic swirl brimming with radiant stars? What were these first stars like, and how were they born?

So far, we have very strong suspicions, but no hard answers. One reason is that the light from this period, called the cosmic dawn, is extremely faint, making it nearly impossible to infer the traits of these first cosmic objects, let alone directly observe them.

But that’s about to change, according to a team of international astronomers. In a new study published in the journal Nature Astronomy, the astronomers argue that we’re on the verge of finally decoding a radio signal that was emitted just one hundred millions years after the Big Bang. Known as the 21 centimeter signal, which refers to its distinct wavelength, this burst of radiation was unleashed as the inchoate cosmos spawned the earliest stars and black holes.

“This is a unique opportunity to learn how the universe’s first light emerged from the darkness,” said study co-author Anastasia Fialkov, an astronomer from the University of Cambridge in a statement about the work. “The transition from a cold, dark universe to one filled with stars is a story we’re only beginning to understand.”

After several hundred thousand years of cooling following the Big Bang, the first atoms to form in the universe were overwhelmingly neutral hydrogen atoms made of one positively charged proton and one negatively charged electron.

But the formation of the first stars unbalanced that. As these cosmic reactors came online, they radiated light energetic enough to reionize this preponderance of neutral hydrogen atoms. In the process, they emitted photons that produced light in the telltale 21 centimeter wavelength, making it an unmistakeable marker of when the first cosmic structures formed. Deciphering these emissions would be tantamount to obtaining a skeleton key to the dawn of the universe.

And drum roll, please: employing the Radio Experiment for the Analysis of Cosmic Hydrogen telescope, which is currently undergoing calibration, and the enormous Square Kilometer Array, which is under construction Australia, the researchers say they’ve developed a model that can tease out the masses of the first stars, sometimes dubbed Population III stars, that are locked inside the 21 centimeter signal.

While developing the model, their key revelation was that, until now, astronomers weren’t properly accounting for the impact of star systems called x-ray binaries among these first stars. These are systems where a black hole or neutron star is stripping material off a more ordinary star that’s orbiting it, producing light in the x-ray spectrum. In short, it appears that x-ray binaries are both brighter and more numerous than what was previously thought.

“We are the first group to consistently model the dependence of the 21-centimeter signal of the masses of the first stars, including the impact of ultraviolet starlight and X-ray emissions from X-ray binaries produced when the first stars die,” said Fialkov. “These insights are derived from simulations that integrate the primordial conditions of the universe, such as the hydrogen-helium composition produced by the Big Bang.”

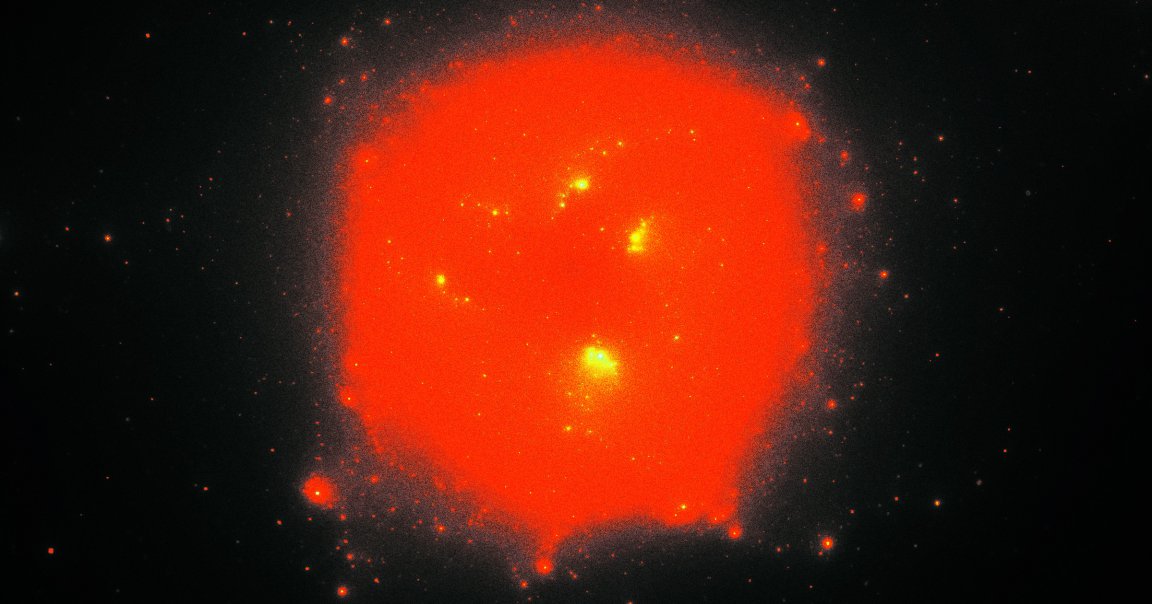

All told, it’s another promising leap forward in the field of radio astronomy, where recent advances have begun to reveal an entire “low surface brightness” universe — and a potentially profound one as well, with the promise to illuminate our understanding of the cosmic dawn as never never before.

“The predictions we are reporting have huge implications for our understanding of the nature of the very first stars in the universe,” said co-author Eloy de Lera Acedo, a Cambridge astronomer and a principal investigator of the REACH telescope. “We show evidence that our radio telescopes can tell us details about the mass of those first stars and how these early lights may have been very different from today’s stars.”

More on astronomy: Scientists Investigating Small Orange Objects Coating Surface of the Moon