The very concept of black holes seems improbable. Albert Einstein infamously refused to believe they could exist, even though his theory of general relativity was instrumental in predicting them.

Now, scientists have witnessed evidence of something about these baffling cosmic monstrosities that further stretches the boundaries of both physics and credulity: a titanic collision of two already enormous black holes so utterly extreme that it has scientists wondering if the event they seem to have detected is even possible.

As detailed in a new yet-to-be-peer-reviewed paper by a consortium of physicists, the resulting black hole, whose signal has been designated GW231123, boasts an astonishing mass about 225 times that of our Sun — easily making it the largest black hole merger ever detected. Previously, the record was held by a merger that formed a black hole of about 140 solar masses.

“Black holes this massive are forbidden through standard stellar evolution models,” Mark Hannam at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), which made the detection, said in a statement about the work. “This is the most massive black hole binary we’ve observed through gravitational waves, and it presents a real challenge to our understanding of black hole formation.”

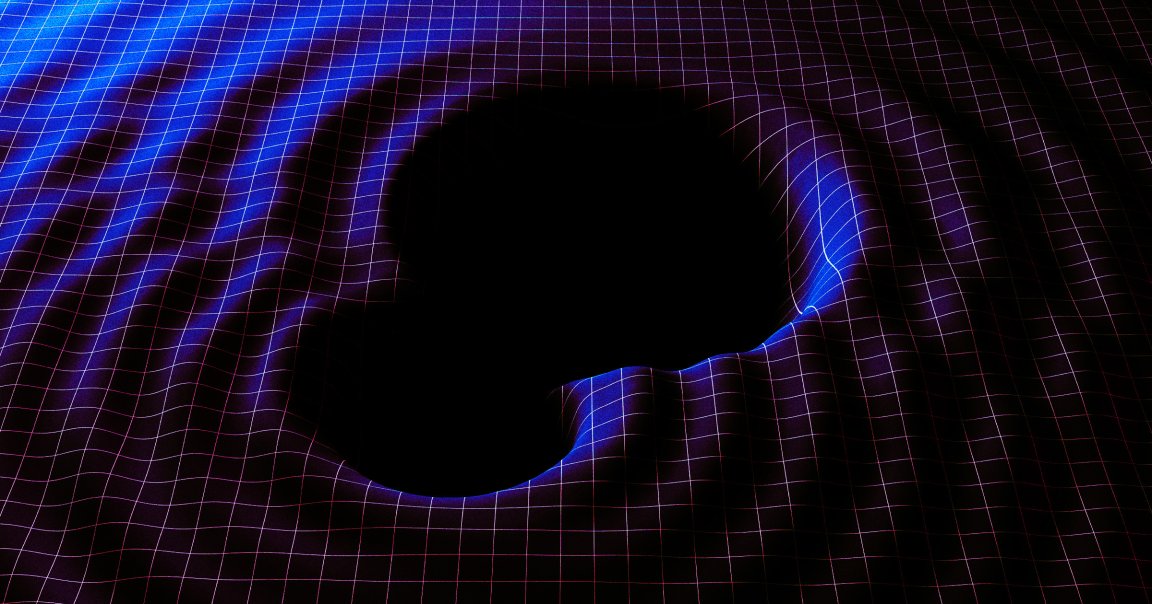

Black holes can produce huge, propagating ripples in spacetime called gravitational waves, which were predicted by Einstein back in 1916. Nearly 100 years later, LIGO — which consists of two observatories on opposite corners of the US — made history by making the first ever detection of these cosmic shudders.

The merger was first spotted in November 2023 in a gravitational wave, GW231123, that lasted just a fraction of a second. Even so, it was enough to infer the properties of the original black holes. One had a mass roughly 137 times the mass of the Sun, and the other was around 103 solar masses. During the lead up to the merger, the pair circled around each other like fighters in a ring, before finally colliding to form one.

These black holes are physically problematic because it’s likely that one, if not both of them, fall into an “upper mass gap” of stellar evolution. At such a size, it’s predicted that the stars that formed them should have perished in an especially vicious type of explosion called a pair-instability supernova, which results in the star being completely blown apart, leaving behind no remnant — not even a black hole.

Some astronomers argue that the “mass gap” is really a gap in our observations and not the cause of curious physics. Nonetheless, the idea is “a hill at least some people were willing to get wounded on, if not necessarily die on,” Cole Miller of the University of Maryland, who was not involved in the research, told ScienceNews.

But perhaps the black holes weren’t born from a single star.

“One possibility is that the two black holes in this binary formed through earlier mergers of smaller black holes,” Hannam said in the statement.

Equally extreme as their weight classes are their ludicrously fast spins, with the larger spinning at 90 percent of its maximum possible speed and the other at 80 percent, both of which are equal to very significant fractions of the speed of light. In earthly terms, it’s somewhere around 400,000 times our planet’s rotation speed, according to the scientists.

“The black holes appear to be spinning very rapidly — near the limit allowed by Einstein’s theory of general relativity,” Charlie Hoy, a member of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration at the University of Portsmouth, said in the statement. “That makes the signal difficult to model and interpret. It’s an excellent case study for pushing forward the development of our theoretical tools.”

The researchers will present their findings at the GR-Amaldi meeting in Glasgow, which takes place this week.

“It will take years for the community to fully unravel this intricate signal pattern and all its implications,” according to LIGO member Gregorio Carullo at the University of Birmingham — so, tantalizingly, we’re likely only scratching the surface of this mystery.

More on space: James Webb Space Telescope Spots Stellar Death Shrouds