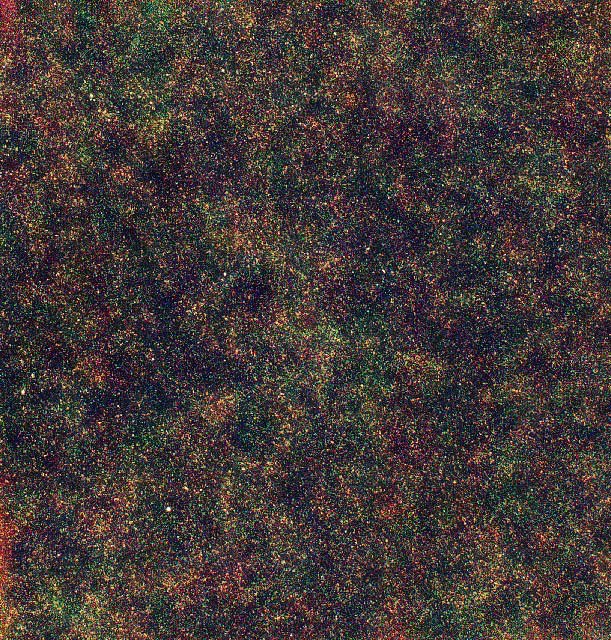

This picture is arguable one of Herschel’s most profound images. If you are tired of seeing the same old sky day after day, take some time to gaze at this beauty. It is sure to give you a different perspective. Similar to the Hubble Ultra-Deep Field, in this image, every speck of light is an entire galaxy, each containing billions of stars billions of light-years away.

In this photo, the telescope shows us the very distant universe. It is the cosmos as it existed some 10 billion years ago (meaning that the light from these glittering beacons took 10 billion light-years to get here). In other words, these tiny specks are extremely young galaxies that appeared shortly after the Big Bang. But of course, keep in mind that “young” is a relative term, but applicable when talking about a universe that is some 14 billion years old.

One of Herschel’s primary mission objectives was to resolve the hazy background seen in the Hubble Ultra Deep Field image – that is where this picture comes in. This resolution helps scientists to peel back the curtain on the early universe and answer important questions. The problem with looking at galaxies that are so young and so distant is that, at this epoch in the universe’s history, galaxies were rather close together. To understand the problem, consider the following:

Our Galaxy, the Milky Way, exists as a part of a large supercluster that is centered about 60 million light-years away. And of course, we aren’t the only supercluster in the universe. There are others. Many others. Yet, the closest neighboring supercluster of galaxies is an astounding around 300 million light-years away (it would take us billions and billions of years to get there using modern technology). However, for comparison, 10 billion years ago, galaxies were only 20 to 30 million light-years apart on average. That makes them rather difficult to image accurately because it is hard to differentiate one from the other.

Herschel used SPIRE, one of its wide field mapping instruments, to take these images. You’re looking at an area covering about 15 square degrees, which is about 60 times the apparent size of the full moon. Professor Asantha Cooray, of the University of California, commented on the significance of this image, stating, “Thanks to the superb resolution and sensitivity of the SPIRE instrument on Herschel, we managed to map in detail the spatial distribution of massively starforming galaxies in the early universe. All indications are that these galaxies are busy. They are crashing, merging, and possibly settling down at centers of large dark matter halos.”