Once an incredibly massive star reaches the end of its lifetime, it goes out in a blaze of glory that culminates in the star exploding as a supernova. Other than gamma ray bursts, supernovae are the most energetic events we are aware of. In just a fraction of a second, these stars release more energy than our Sun will over the course of its entire lifetime. However, there are various types of stellar explosions, Naturally, some are generated in ways that don’t include a core collapse.

Now, astronomers from Georgia State University’s ‘Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy’ (CHARA) have, for the first time, witnessed the thermonuclear fireball expanding away from a nova in unprecedented resolution. The nova itself, called Nova Delphinus 2013, lurks in the constellation of Delphinus about 14,800 light years from Earth. Found by a Japanese amateur astronomer back in 2013, it was originally believed to be a star.

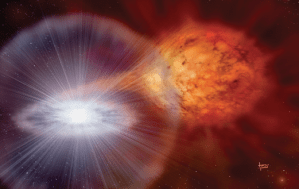

Now, however, we know that the “star” was actually two stars — a large star with an expansive halo of gaseous material, along with a dense white dwarf (a remnant of a Sun-like star that has passed beyond the main-sequence threshold, into one of the final stages of stellar evolution) — from a binary star system. When two are located in such a close proximity, orbiting a common center of mass, the smaller one tends to siphon material from the larger companion, slowly building up its own hydrogen envelope. Once enough gas has accumulated — by some estimates, 650 feet (200 meters) will do — it ignites a chain reaction within the white dwarf itself

In the grand scheme of things, a few weeks isn’t a lot of time, but considering how quickly such events unfold, astronomers must take the first chance they can to investigate before their window of time passes. With this binary star system, 15 hours after it was found — and less than 24 hours after the explosion itself — researchers already had their telescopes pointed toward the source of the nova (though it’s important to remember that, due to the fact that the star is more than 15,000 light-years from Earth, it took just as long for the light to travel all the way to Earth. Therefore, the nova itself ignited 15 thousand years ago). Over 27 days of the 8 subsequent weeks, the telescopes that comprise the CHARA Array observed and measured the fireball expanding away from the nova.

From the press release:

The CHARA facility is on the grounds of historic Mount Wilson Observatory in the San Gabriel Mountains of Southern California and is operated by Georgia State. The CHARA Array uses the principles of optical interferometry to combine the light from six telescopes to create images with very high resolution, equivalent to a telescope with a diameter of more than 300 meters. This makes it capable of seeing details far smaller in angular extent than traditional telescopes on the ground or in space. It has the power to resolve an object the size of a U.S nickel on top of the Eiffel tower in Paris from the distance of Los Angeles, Calif.

During the first CHARA observation, the physical size of the fireball was roughly the size of the Earth’s orbit. When last measured 43 days after the detonation, it had expanded nearly 20-fold, at a velocity of more than 600 kilometers per second, to nearly the size of Neptune’s orbit, the outermost planet in our solar system.

Images of the fireball were created from the interferometric measurements using the University of Michigan Infrared Beam Combiner (MIRC), an instrument that combines all six telescopes of the CHARA Array simultaneously to create images. The observations reveal the explosion was not precisely spherical and the fireball had a slightly elliptical shape. This provides clues to understanding how material is ejected from the surface of the white dwarf during the explosion.

The CHARA observations also showed the outer layers became more diffuse and transparent as the fireball expanded. After about 30 days the researchers saw evidence for a brightening in the cooler, outer layers, potentially caused by the formation of dust grains that emit light at infrared wavelengths.

[Reference: GSU]

To summarize, “The observations produced the first images of a nova during the early fireball stage and revealed how the structure of the ejected material evolves as the gas expands and cools. It appears the expansion is more complicated than simple models previously predicted,” scientists said.

Moving forward, astronomers hope to measure the fireballs surrounding various other novae. By comparing and contrasting, they can have better insight into the nature of novae themselves. Additionally, they can use this information to adjust their models accordingly.

The findings have been published in a recent issue of Nature.