Scientists as eminent as Stephen Hawking and Carl Sagan have long believed that humans will one day colonize the universe. At least, that this is theoretically possible (and even imperative if we are to survive). But how easy would it be, why would we want to, and why haven’t we seen any evidence of other life forms making their own bids for universal domination?

Dr Stuart Armstrong and Dr Anders Sandberg from Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute (FHI) attempted to answer these questions. But to begin, we must start at the the Fermi paradox – the discrepancy between the likelihood of intelligent alien life existing and the absence of observational evidence for such an existence.

Dr Armstrong says: “There are two ways of looking at our paper. The first is as a study of our future – humanity could at some point colonize the universe. The second relates to potential alien species – by showing the (relative) ease of crossing between galaxies, it makes the lack of evidence for other intelligent life even more puzzling. This worsens the Fermi paradox.”

The paradox, named after the physicist Enrico Fermi, is something of particular interest to the academics at the FHI – a multidisciplinary research unit that enables leading intellects to bring the tools of mathematics, philosophy and science to bear on big-picture questions about humanity and its prospects.

Dr Sandberg explains: “Why would the FHI care about the Fermi paradox? Well, the silence in the sky is telling us something about the kind of intelligence in the universe. Space isn’t full of little green men, and that could tell us a number of things about other intelligent life – it could be very rare, it could be hiding, or it could die out relatively easily. Of course it could also mean it doesn’t exist. If humanity is alone in the universe then we have an enormous moral responsibility. As the only intelligence, or perhaps the only conscious minds, we could decide the fate of the entire universe.”

READ NEXT: 10 Solutions to the Fermi Paradox

According to Dr Armstrong, and a number of other scientists, one possible explanation for the Fermi paradox is that life destroys itself before it can spread. “That would mean we are at a higher risk than we might have thought,” he says. “That’s a concern for the future of humanity.”

Dr Sandberg adds: “Almost any answer to the Fermi paradox gives rise to something uncomfortable. There is also the theory that a lot of planets are at roughly at the same stage – what we call synchronized – in terms of their ability to explore the universe, but personally I don’t think that’s likely.”

As Dr Armstrong points out, there are Earth-like planets much older than the Earth – in fact most of them are, in many cases by billions of years.

Dr Sandberg says: “In the early 1990s we thought that perhaps there weren’t many planets out there, but now we know that the universe is teeming with planets. We have more planets than we would ever have expected.”

A lack of planets where life could evolve is, therefore, unlikely to be a factor in preventing alien civilizations. Similarly, recent research has shown that life may be hardier than previously thought, weakening further the idea that the emergence of life or intelligence is the limiting factor. But at the same time – and worryingly for those studying the future of humanity – this increases the probability that intelligent life doesn’t last long.

Ultimately, the scientists ask, if we can get out into the cosmos, just how far and wide a civilization like humanity could theoretically spread.

Could We Do It?

Dr Sandberg says: “If we wanted to go to a really remote galaxy to colonize one of these planets, under normal circumstances, we would have to send rockets able to decelerate on arrival. But with the universe constantly expanding, the galaxies are moving further and further away, which makes the calculations rather tricky. What we did was combine a number of mathematical and physical tools to address this issue.”

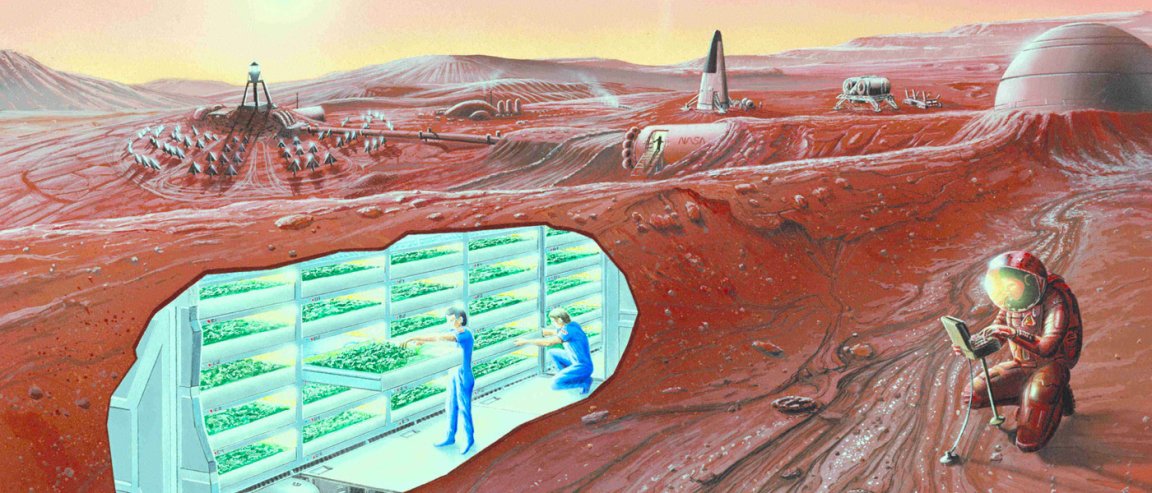

Dr Armstrong and Dr Sandberg argue that, given certain technological assumptions (such as advanced automation or basic artificial intelligence, capable of self-replication), it would be feasible to construct a Dyson sphere, which would capture the energy of the sun and power a wave of intergalactic colonization. Yes, this would be an amazing feat, one of engineering genius. But the scientists argue that humanity could do it, and that the process could be initiated on a surprisingly short timescale.

Why Would We Want To?

But why would a civilization want to expand its horizons to other galaxies? Dr Armstrong says: “One reason for expansion could be that a sub-group wants to do it because it is being oppressed or it is ideologically committed to expansion. In that case you have the problem of the central civilization, which may want to prevent this type of expansion. The best way of doing that Is to get there first. In short, pre-emption is perhaps the best reason for expansion.”

Dr Sandberg adds: “Say a race of slimy space aliens wants to turn the universe into parking lots or advertising space – other species might want to stop that. There could be lots of good reasons for any species to want to expand, even if they don’t actually care about colonizing or owning the universe.”

He concludes: “Our key point is that if any civilization anywhere in the past had wanted to expand, they would have been able to reach an enormous portion of the universe. That makes the Fermi question tougher – by a factor of billions. If intelligent life is rare, it needs to be much rarer than just one civilization per galaxy. If advanced civilizations all refrain from colonizing, this trend must be so strong that not a single one across billions of galaxies and billions of years chose to do it. And so on. We still don’t know what the answer is, but we know it’s more radical than previously expected.”

Ultimately, however, the scientists argue that, based on our current knowledge and understanding of the physics that governs the universe, such expansion is possible. Perhaps we will find a solution to the Fermi Paradox once we venture out into the cosmos and find whatever is awaiting us…

Provided by Stuart Gillespie, University of Oxford