As children, we were always told to avoid strangers. Yet today we’re comfortable getting into their cars via Uber or Lyft, or staying in their homes with Airbnb. As our enthusiasm in trusting one another has risen, it’s declined when it comes to institutions, from banks to media outlets to governments. Why is this happening, and what does it have to do with the omnipresence of technology?

This is the subject of a new book called Who Can You Trust? How Technology Brought Us Together – and Why It Could Drive Us Apart, published on November 14 by PublicAffairs. Its author, Rachel Botsman, is a visiting lecturer at the University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School, and one of the world’s foremost experts on trust. She recently chatted with Futurism about what she learned about trust, why this shift is different than others in the past, and how we avoid a dystopian future.

This interview has been slightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Futurism: Where did the inspiration for this book come from? You open with the 2008 financial crisis, but I got the sense that this was just the tip of the iceberg in terms of people mistrusting institutions.

Rachel Botsman: In 2009, I published my first book, What’s Mine is Yours, about the sharing economy. The piece that always fascinated me was how technology could enable trust between total strangers over the internet to make ideas that should be risky, such as sharing your home or a ride, mainstream. And so I immersed myself in understanding how trust in the digital age really works. Through that research, I discovered that my interest was much broader — I wanted to understand how we place our faith in things, what influences where we place our faith, and what happens when our confidence is undermined in systems such as the financial system or political system. So I started to wonder whether the current crisis of trust in institutions and the rise of technology facilitating trust between strangers were connected in some way.

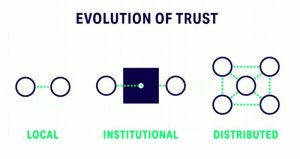

That led to what I think is the central idea of this book: that trust is shifting from institutions to individuals. I felt that this was a timely and important book to write because we’re already seeing the profound consequences of this trust shift, from the influence on the presidential election to Brexit to algorithms and bots.

F: Is trust being lost or is it simply shifting?

RB: I don’t like this narrative that trust is in crisis. In fact, it’s dangerous because it only serves to amplify the cycle of distrust. Trust is like energy — it doesn’t get destroyed, it changes form. You need trust in society for people to collaborate, to transact – to even leave the house. A society cannot survive, and it definitely cannot thrive without trust. For a long time in history, trust has flowed upwards towards the CEOs, towards experts, academics, economists, and regulators. Now that’s being inverted — trust is now flowing sideways, between individuals, ‘friends,’ peers and strangers. There’s plenty of trust out there, it’s just flowing to different people and places.

It’s also false to say we need more trust. Of course, we can have too much trust in the wrong people, in the wrong things. We can give our trust away too easily.

Trust is like energy

it doesn’t get destroyed, it changes form.

F: Institutions are, of course, made up of people, which makes it kind of funny that we’re less willing to trust those institutions. Where does that break down?

RB: I think it’s an issue of scale, a feeling that organizations and institutions beyond a certain scale lose their human-ness. It’s also a problem when the people inside the organization feel like they’re serving the system instead of the people. A huge trust problem takes hold when the system becomes so large that there’s no way the intentions of the organization, no matter how good their employees or their culture, are aligned with their users or customers. You see that in the banking industry — even if a particular bank is compliant and has a good culture and smart employees, it’s really hard for consumers to look at that bank when they come out with humongous profits and say, ‘Oh I trust your intentions are aligned with mine.’

F: I was struck by your mentions of dystopian TV shows, novels, and movies. Is there something about this moment that makes dystopia feel particularly relevant?

RB: You ought to see my Netflix recommendations! We’re currently experiencing a trust vacuum that arises when our confidence in facts and the truth are continually called into question. A trust vacuum is created, and that is dangerous. That vacuum is filled by people with agendas, masterfully selling themselves as anti-establishment, and telling whatever lie plays to the anti-elitist sensibilities currently felt by people. The rise of the ‘anti-politician’ — from Nigel Farage to Donald Trump — is an indicator that the biggest trust shift we’ve seen in a generation is underway. In a vacuum, we become more susceptible and vulnerable to conspiracy theories, to different voices that know how to speak to people’s feelings over facts, to this new intoxicating form of transparency. Those scratching their heads because the most qualified candidate in history lost [an election] are overlooking a growing distrust of elites, the inversion of influence and rising skepticism about everything — from the validity of news to a deep suspicion of established political systems. I think people are trying to understand the dystopia we are living through.

F: What makes this moment different from other moments of mistrust we’ve had in the past?

RB: Of course, in the past we’ve had massive breaches of trust, such as Watergate or the Tuskegee Study scandal. However, two things are happening that make this moment unique. First of all, there’s a historic decline in trust across all major institutions including charities and religious organizations. It’s become systemic that people have just lost their faith in the establishment and in the elite. And that’s become like a virus that is spreading and being spread fast.

The second obvious point is that technology amplifies our fears, often baselessly. Social media “weaponizes” misinformation creating digital wildfires that spread anger and anxiety surrounding institutions. It’s also much harder to keep misdeeds hidden or to try to cover acts up with PR puffery. Take the Weinstein phenomenon that’s going on now — it illustrates how fast one incident becomes a social crisis and then a movement.

F: Tell me a little about the Chinese social credit system. Before reading the excerpt of that chapter of your book in Wired UK, I had never heard of it. What do you make of it overall?

RB: The Chinese government has its social citizen scores (SCS) that are voluntary now but will be mandatory by 2020. And then there are companies in China such as Tencent and Alibaba that have their own scoring mechanism, but these are different to the way we think of credit scoring. There’s an important distinction between the government and company rating systems.

The interesting thing is observing how the government positioned the citizen scoring — the economic rationale behind it, seeing how the reward mechanisms were the first piece introduced, and then the penalties later followed. For example, earlier this year more that 6 million Chinese were banned from taking flights. Plus, the rating of Chinese citizens will be publicly ranked against that of the entire population and used to determine their eligibility for a mortgage or a job, where their children can go to school— or even just their chances of getting a date. It’s game-ified obedience.

F: You made the connection to Western society, how we have versions of a system like this though not quite so extreme. Does it seem likely to you that this sort of thing will become more widespread to other systems and other governments?

RB: Yeah, the hardest part about getting the trust scoring chapter right is there is a tendency to view this system through a Western lens. To make a quick judgement and conclude, ‘Well that’s never going to happen to us. Only in China.’ But today it’s in China, tomorrow it could be in a place near you. When you dig in and look at the level of surveillance going on in the West, from governments to companies, and how much they know about us, it is staggering. There are all kinds of ways we are being judged and assessed that would make us extremely uncomfortable if we knew. Just look at the outcry when we discovered the NSA was listening and collecting information on regular citizens. The Chinese could make the argument that at least their system is transparent. At least people know that they’re being rated.

What is inevitable is that our identity and our behaviors will become an asset. I guess the question is: Who will own the data? Hopefully we’ll get to a place where it will be us as individuals so that we will be more in control about how that data is used and sold, and that we can use it to our benefit. As opposed to a tech company like Google, Amazon or Facebook or, even worse, the government having that kind of control over our lives.

There are all kinds of ways we are being judged and assessed that would make us extremely uncomfortable if we knew.

F: You mention tracking and surveillance. It’s certainly something that came up a lot in the book, and that many of us have been thinking about. What is the relationship between trust and surveillance?

RB: Well surveillance isn’t particularly good when it comes to trust. Think of a personal relationship. If a partner is reading your messages or tracking where you are all the time, that is a low trust relationship! I define trust as ‘a confident relationship with the unknown.’ If you trust surveillance, there must be faith that the tracking and data captured is being used to your benefit. The tricky part is the black box, when you don’t know what’s happening with your information, and you don’t trust the system or the entity that is managing the data. That’s why we often hear this cry ‘we need more transparency.’ But when we need things to be transparent, we’ve given up on trust.

F: Where does artificial intelligence fit in this larger shift to distributed trust?

RB: We’ve talked about trust shifting from institutions to individuals. That individual might be a human, or it might be an artificially intelligent bot. It is going to become increasingly difficult to be able to tell if you’re interacting with a human or an algorithm. Deciding who is trustworthy, getting the right information, and reading the right ‘trust signals,’ is hard enough with human beings. Think of the last time you were duped. But when we start outsourcing our trust to algorithms, how do we trust their intentions? And when the algorithm or the bot makes a decision on your behalf that you don’t agree with, who do you blame?

F: What stands between our present day and the possibility of this dystopian future you’ve hinted at? What could prevent this from going totally awry?

RB: Tech companies will enter a new era of accountability. The idea that the likes of Uber, Facebook, and Amazon are immune to regulation, tax, and compliance, that they’re just these disruptive pathways that connect people and resources, I think those days are over. There will be a sweeping wave of regulation that looks at platforms’ responsibilities to reduce the risk of bad things happening and also, how they respond when things go wrong.

Some institutions will use this period of change an opportunity — proving to society that we need institutions, that they present norms and rules and systems, and they can be trustworthy. We’re seeing this with the New York Times; it has had its best year in terms of paid subscriptions. But institutions can’t just say, ‘You should trust us.’ They have to demonstrate that they’re trustworthy, that we can believe in their systems.

F: How do you think this larger shift in trust will shape us moving forward? Shape how we spend our money and how we live our lives?

RB: It’s very easy to blame institutions, but we need to acknowledge that as individuals we have a responsibility to think about where we place our trust and with whom. Too often, we let convenience trump trust. For instance, if we want high-quality, fact-checked journalism media, we should pay for it and not get our news directly from Facebook. We’re all guilty of this. I was talking to someone the other day who was saying how much he hates Uber, how ‘It’s a devil of a company,’ I politely inquired whether the app was on his phone, ‘Well I haven’t had a chance to delete it and download Lyft,’ he rather defensively replied. It would take one minute [to do that]. It’s kind of like the citizen who complains about the outcome of an election but did not vote. So, my hope is that we use our anger productively. We have more power than we realize in this trust shift that feels so big and out of control.

F: So what’s the answer to the title of your book? Who can you trust?

RB: It’s a complicated question. It depends on the context; you can trust people to do certain things in certain situations. I mean you can trust Trump to tweet something ridiculous in the wee hours of the morning but not to negotiate with North Korea. You can hopefully trust me to teach or to write an article, but you shouldn’t get into a car with me because I’m a terrible driver. When we talk about trust, we really need to talk about context. I hope that, after reading my book, people are better equipped to take a ‘trust pause,’ to ask: Is this person, product, company, or piece of information worthy of my trust?