‘Seams’ Like Magic

The clothing industry has long been using machinery for garment-making: fabrics can be woven by machines, and then cut into pieces by computer-controlled cutting machines. But a large part of the process is still reliant on human workers; pieces of clothing still need to be manually sewn together, and quality control still relies on human eyes.

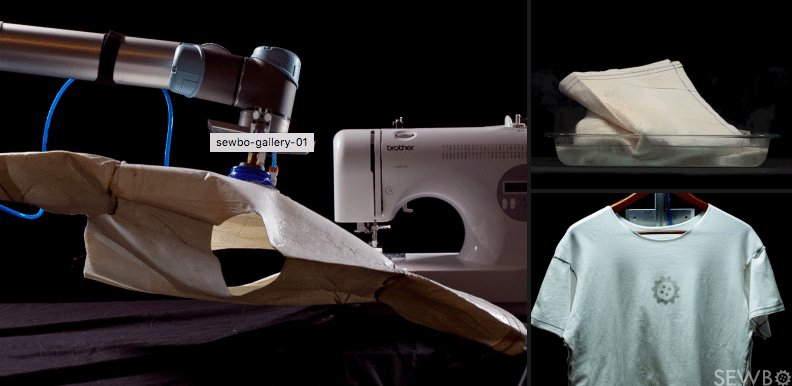

Jonathan Zornow’s one-man startup, Sewbo, seeks to revolutionize the garment industry by automating feeding the fabric to the sewing machines. Zornow’s process works by first dipping the fabric into a polymer solution. The chemical used is a water-soluble plastic similar to those used in 3D printed objects. The cloth becomes a stiff, workable panel. It can then be mechanically guided by a robotic arm through a machine where the cutting and sewing patterns are already encoded. The polymer interspersed in the fabric is washed off with hot water to finish the garment.

Zornow has demonstrated Sewbo in creating t-shirts, and says the system can learn patterns for any article of clothing. The system costs about $35,000.

Taking The Sweat Out Of Sweatshop

A future of fully-automated clothing may allow manufacturers to shorten supply chains and create higher-quality clothing at lower costs. However, controversy shrouds bargain clothing and “fast fashion,” an industry fueled by cheap labor, unregulated work practices, and human trafficking.

The Center for American Progress found that in 2011, 15 of the top apparel exporters to the U.S. paid their Chinese garment workers an average monthly real wage of $324.90. Bangladeshi workers earned just $91.45. Meanwhile, U.S. sewing machine operators earn an average monthly wage of $1,922, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Innovations like Zornow’s could take the sweat out of the sweatshops, but where would the masses of factory workers then go?

Scenarios like this lead us to question the coming age of autonomy in a time of leaping technological advances. Rice University computer scientist Moshe Vardi, who expects that within 30 years, machines will be capable of doing almost any job that a human can, says, “if machines are capable of doing almost any work humans can do, what will humans do?”

“Humanity is about to face perhaps its greatest challenge ever, which is finding meaning in life after the end of ‘In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread.’ We need to rise to the occasion and meet this challenge before human labor becomes obsolete.”

Ultimately, it’s up to us to find the balance in using technology to improve lives. As Vardi says, we must ask ourselves, “does the technology we are developing ultimately benefit mankind?”