Brain Training

Among the brain diseases associated with aging, there are none quite like Alzheimer’s and dementia. Globally, the prevalence of both neurodegenerative diseases is alarming. According to Alzheimer’s Disease International, almost 50 million people suffer from dementia worldwide, while some 44 million people were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2016 alone. These figures make it especially crucial to find cures, or at least better treatments and preventative measures, for both.

Enter the Indiana University (IU) School of Medicine, which conducted a mental exercise program facilitated by a team of researchers from the University of South Florida, Pennsylvania State University, and Moderna Therapeutic, under the leadership of psychiatry professor Frederick W. Unverzagt.

The results of this Advanced Cognitive Training in Vital Elderly (ACTIVE) program, which they published in the journal Alzheimer & Dementia Translational Research and Clinical Interventions, showed that cognitive training known as speed processing was capable of significantly lowering the risk of developing dementia among the 2,802 older adults who participated.

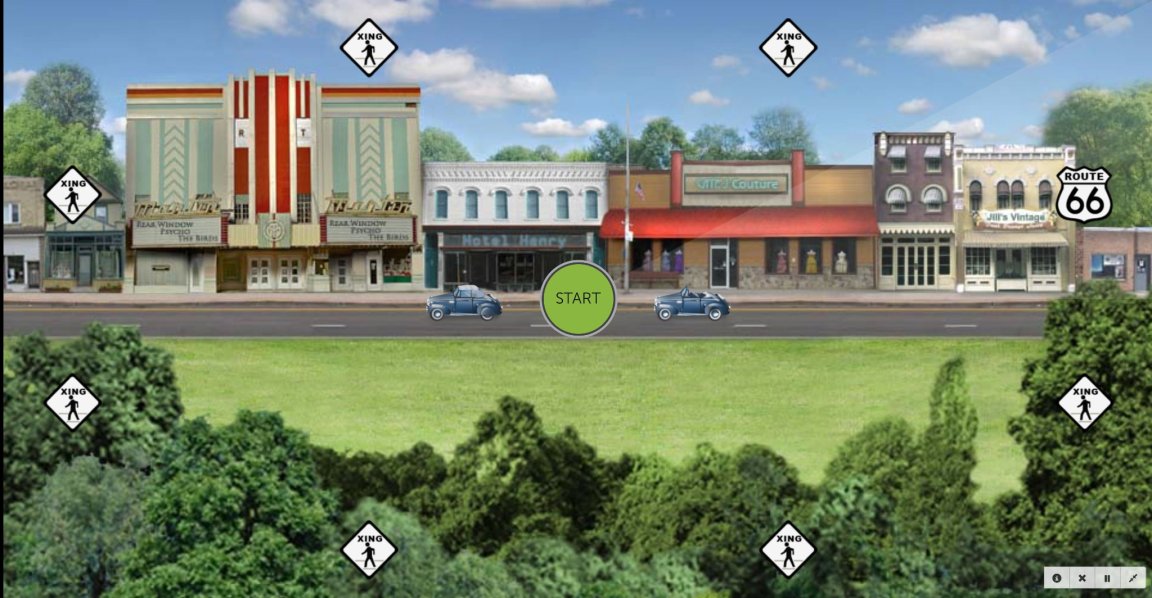

Within this study, the speed processing involved 10 one-hour sessions, spread out over a period of five to six weeks. Adults aged 65 years and older were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups, three of which involved practicing strategies meant to improve cognitive function — like memory and problem solving — and the fourth group served as a control.

Assessments were done after one, two, three, five, and then 10 years, with only 1,220 participants completing the full assessment cycle because of attrition due to a variety of reasons, including death. Throughout the 10-year period, only 260 participants developed dementia, which showed that the risks for getting the disease was 29 percent lower than for those in the control group.

Boosting Hopes

While 29 percent may not seem like much, it is a significant statistic that shows that it is possible, at least in part, to prevent against Alzheimer’s and dementia. At the very least, the researchers believe that it supports the notion that staying mentally active is essential as a person ages.

“It’s completely consistent with a large literature that talks about the beneficial effects of engagement, broadly considered, from an occupational standpoint, interpersonal engagement, leisure activity engagement,” Unverzagt explained in a Q&A blog post. “All of that epidemiological research has found support for the idea that those things are helpful to brain health, and in terms of risk for later development of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, engagement with those things is associated with a lower risk. It’s quite consistent with that literature.”

Unverzagt, however, admitted that the results of the program have limitations, particularly because there were a relatively small number of patients who participated, despite the study being quite extensive in monitoring progress over 10 years. “We would consider this a relatively small dose of training, a low intensity intervention. The persistence – the durability of the effect was impressive,” he said in an IU press release.

More research is definitely warranted, which could include further determining whether the effects of speed processing could be attributed to the different methodology used or the different types of thinking the cognitive training focused on. “Our study can’t separate those. That would be an area to explore in future research,” Unverzagt said in the Q&A post.