Robots and Machines

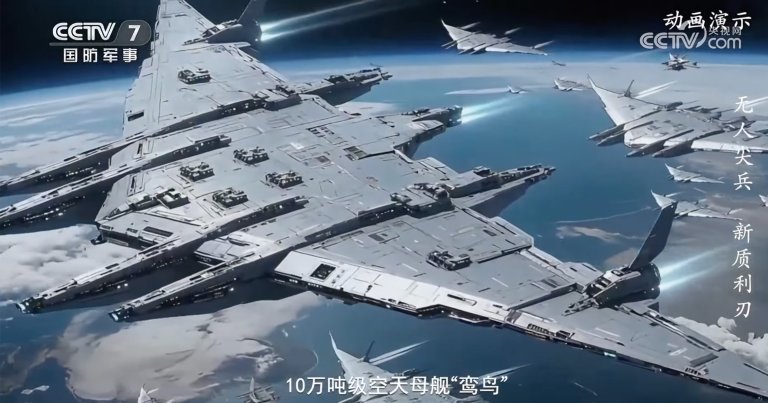

We are constructing a futuristic society which is populated by autonomous flying machines, houses are printed on-demand, and our companions are highly evolved robots. These advancements in IoT and robotic automation are allowing us to re-imagine and re-engineer our world. We’ll be there to give you a look into what this new world will hold.