Hell and Back

NASA’s Parker Solar probe didn’t quite fly into the Sun, but it did the next best thing. In 2021, the probe barrelled straight through the heart of a huge coronal mass ejection — and survived — earning it the title as the first spacecraft to “touch” our star.

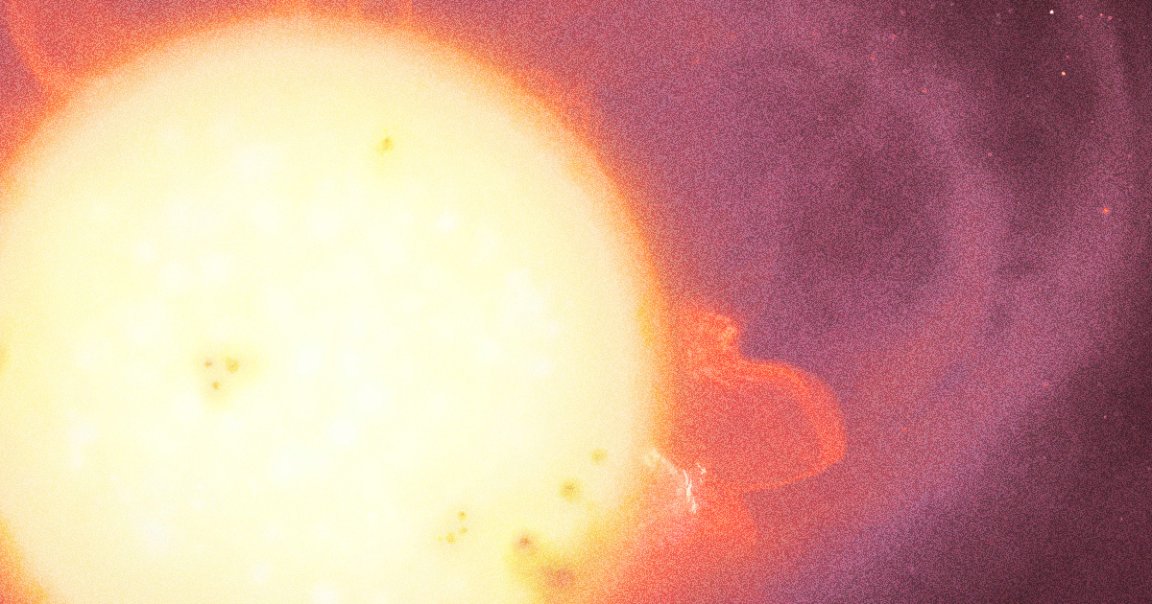

Now, a new study published in the Astrophysical Journal reveals some of the remarkable findings captured by the probe during its journey, including mindblowing images of the CME’s tempestuous interior in visible light.

The photos, assembled into a video below, depict turbulent eddies storming past the probe that the researchers believe are the signatures of a rarely observed phenomenon called Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities (KHI).

If so, it’s the closest look yet of these interactions in a coronal mass ejection, deepening our understanding of how these huge expulsions of plasma blow through our solar system.

“We never anticipated that KHI structures could develop to large enough scales to be imaged in visible light CME images in the heliosphere when we designed the instrument,” said Angelos Vourlidas.

Cooked

Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities are seldom observed on Earth, where they most visibly manifest as wave-like fluctus clouds. They arise from the interaction of two adjacent streams of fluids moving at different velocities.

In a coronal mass ejection, this can occur at the boundary between flows of hot plasma and solar wind, a continual stream of charged particles emitted from the Sun’s upper atmosphere, the corona.

“The turbulence that gives rise to KHI plays a fundamental role in regulating the dynamics of CMEs flowing through the ambient solar wind,” co-author Evangelous Paouris, an astrophysicist at George Mason University and a member of the Wide-field Imager For Parker Solar probe Science Team, said in a statement about the work. “Hence, understanding turbulence is key in achieving a deeper understanding of CME evolution and kinematics.”

Mass Attack

There’s a lot we still don’t understand about CMEs. Their occurrence can be spontaneous and hard to predict. They’re usually associated with sunspots and solar flares, but some erupt in regions of the Sun with no such activity.

Scientists have good reason to be worried about their ambiguities. The solar explosions hurl billions of tons of material into space, bringing with them extremely powerful magnetic fields. When directed towards Earth, they can cause huge disruptions to our electric infrastructure, such as power blackouts and cutting off satellite-based communications.

These latest findings, the researchers claim, could help us eventually forecast their occurrence.

“The direct imaging of extraordinary ephemeral phenomena like KHI with WISPR/PSP is a discovery that opens a new window to better understand CME propagation and their interaction with the ambient solar wind,” Paouris said.

More on the Sun: You May Be Able to See Twisted Towers of Fire During Eclipse